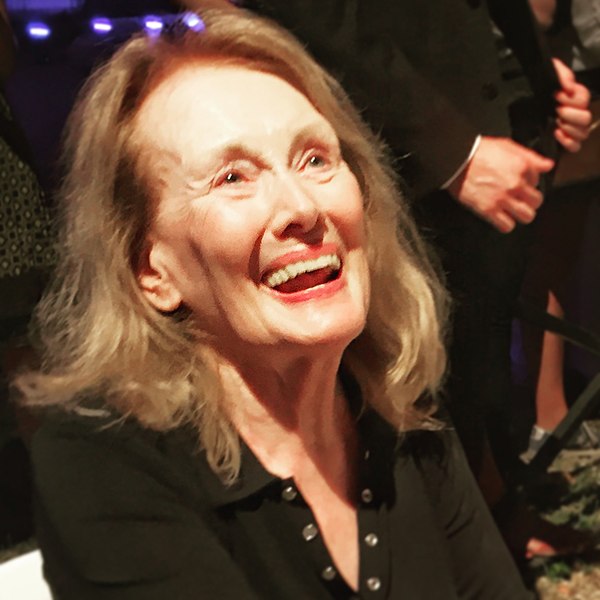

The following is re-posted from the Conversation. We share this reflection because Annie Ernaux’s writing centers socio-political context and the experiences, and suffering, of the French working-class.

The French author Annie Ernaux has won the 2022 Nobel prize in literature at the age of 82. Of the 119 awarded, Ernaux is only the 18th woman Nobel laureate in literature and the first French woman to have won the prize.

The academy praised her “for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory”.

From her first book Cleaned Out in 1973, Ernaux’s work has been closely informed by her own life experiences. She has continued to surprise and inspire readers with coverage of daring topics and her innovative approach to genres. Her body of work includes discussions on the act and art of writing, texts incorporating personal photographs, intimate and public diaries, and life-writing that refuses to be contained by categories.

Class conflict

Born in 1940, Ernaux was brought up in Yvetot in Normandy. She is the only daughter of working-class parents who ran a cafe-cum-grocers, and her childhood was underpinned by class tensions within the family home and outside it. Ernaux attended a private Catholic girls’ school for her secondary education, which fuelled social divisions between her and her parents – in particular her father, which she explores in her fourth publication A Man’s Place.

Growing up in a socially divided environment meant Ernaux felt ashamed of the supposedly distasteful aspects of her upbringing, such as the working-class environment of her father’s cafe or her mother’s shirking of the norms of middle-class housewifery and femininity, which she writes about in A Frozen Woman.

Her childhood was immersed in working-class culture, popular songs and the romantic novels her mother consumed. But from an early age, she was also an avid reader of “classic” French texts. She then studied literature at Rouen university and went on to teach it at secondary school before becoming a full-time writer in the 1970s. This experience gave Ernaux knowledge of French theories and practices of writing, which is evident in her references to authors such as Honore de Balzac, Marcel Proust and Simone de Beauvoir and her self-reflexive comments on the act of writing.

As a writer, she realised that her daily life was not represented in either the French literature she read at home or in the classrooms she learnt and later taught in. It was at school that she became aware of a “familiarity, a subtle complicity” as her teachers avidly listened to the stories of her middle-class schoolmates but silenced her attempts to speak about her home life. These experiences permeate her work, which repeatedly touches on the conflict between what she calls “the dominant class” and “the dominated class”, referencing the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu.

Her first three novels, Cleaned Out, Do What They Say or Else and A Frozen Woman, form a trilogy of autobiographical novels. These works broadly detail the socialisation of a working-class girl who has a middle-class education and then marriage. Her protagonist is a woman who, like so many of Ernaux’s readers, identifies as a “class defector”.

In subsequent works, Ernaux considered fictionalised accounts of her origins a form of betrayal because they ran the risk of exoticising her family and class origins.

Ernaux’s acute awareness of the formative influence of class underpins her entire body of work and in the wake of her win, many in France praised her work for its ongoing focus on the French working-class experience.

Flat writing

Following this trilogy, Ernaux adopted the writing style for which she has since become well-known, typically referred to as “l’écriture plate” (literally “flat writing”). This pared-down, understated style is coupled with a fluid approach to genre that incorporates elements of ethnography, autobiography and sociology. As she comments in A Man’s Place:

This neutral way of writing comes to me naturally, it is the very same style I used when I wrote home telling my parents the latest news.

The chairman of the Nobel Literature committee, Anders Olssen, described Ernaux’s work as “uncompromising and written in plain language, scraped clean”.

This approach to writing is underpinned by a mission. Ernaux believes that writing about the self inevitably involves writing about a socio-political context, and thereby extends the representativeness of her own experience. By writing simply about her own experiences, she also wants to write into literature the collective experience of the French working-class.

That desire to give voice to marginalised experiences is further illustrated in two of her “external diaries”, Exteriors and Things Seen, which record the everyday exchanges of people in outside spaces such as the supermarket or when commuting on the Paris metro.

She has also published more intimate diaries composed during significant stages of her life. I Remain in Darkness was written during her mother’s decline from Alzheimer’s. Getting Lost is a diary she kept during a passionate affair with a married man – a love affair she also described in her work Simple Passion. The honesty with which she details her obsession with this man struck a chord with many of her female readers.

Her literary approach typically incorporates self-reflexive remarks where she comments on the challenges she faces in turning lived experiences into literary form.

It is that openness and sense of writer-reader intimacy that partly explains her popularity. Her courage in exploring and exploding generic expectations is also reflected in the content of her work. She writes about a range of taboo subjects including her backstreet abortion (Cleaned Out and Happening, which was recently made into a film), sexual intimacy and issues of consent, breast cancer and her dead sister (L’Autre Fille).

Her most famous work, The Years, is considered to be her magnum opus. It can be read as a further example of a “public diary” in that it covers the socio-cultural history of France, mixing her own story (relayed through the representative “she”) with the collective story of her generation. Nominated for the International Booker Prize in 2019, The Years made English-speaking audiences aware of her work – and that attention has now happily been extended by the jury of the Nobel prize in literature.

Like many of the women prizewinners who have preceded her, including Toni Morrison and Alice Munro, Ernaux has spent her writing life giving voice to the experiences of those who remain under- or unrepresented in literature. This award will allow these voices to ring out all the more clearly.![]()

Siobhán McIlvanney, Professor in French and Francophone Women’s Writing; Head of Department of French, King’s College London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments