Originally published July 30, 2019.

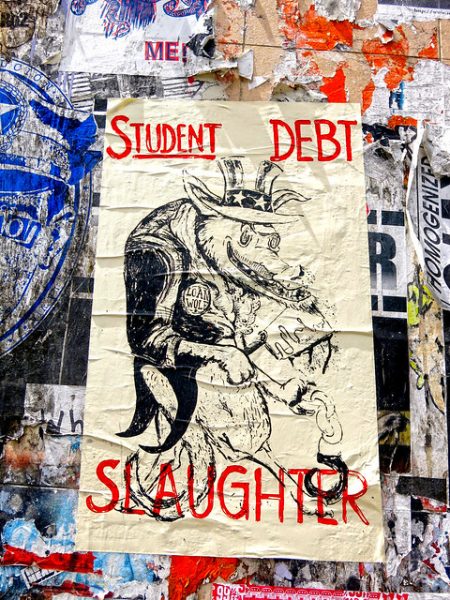

As candidates gear up for this week’s democratic debates, constituents continue to voice concerns about the student debt crisis. Recent estimates indicate that roughly 45 million students in the United States have incurred student loans during college. Democratic candidates like Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders have proposed legislation to relieve or cancel this debt burden. Sociologist Tressie McMillan Cottom’s congressional testimony on behalf of Warren’s student loan relief plan last April reveals the importance of sociological perspectives on the debt crisis. Sociologists have recently documented the conditions driving student loan debt and its impacts across race and gender.

In recent decades, students have enrolled in universities at increasing rates due to the “education gospel,” where college credentials are touted as public goods and career necessities, encouraging students to seek credit. At the same time, student loan debt has rapidly increased, urging students to ask whether the risks of loan debt during early adulthood outweigh the reward of a college degree. Student loan risks include economic hardship, mental health problems, and delayed adult transitions such as starting a family. Individual debt has also led to disparate impacts among students of color, who are more likely to hail from low-income families. Recent evidence suggests that Black students are more likely to drop out of college due to debt and return home after incurring more debt than their white peers. Racial disparities in student loan debt continue into their mid-thirties and impact the white-Black racial wealth gap.

- Jason N. Houle and Fenaba R. Addo. 2018. “Racial Disparities in Student Debt and the Reproduction of the Fragile Black Middle Class.” Sociology of Race and Ethnicity.

- Jason N. Houle and Cody Warner. 2017. “Into the Red and Back to the Nest? Student Debt, College Completion, and Returning to the Parental Home among Young Adults.” Sociology of Education 90(1): 89-108.

- Brandon A. Jackson and John R. Reynolds. 2013. “The Price of Opportunity: Race, Student Loan Debt, and College Achievement.” Sociological Inquiry 83(3): 335-368.

Other work reveals gendered disparities in student debt. One survey found that while women were more likely to incur debt than their male peers, men with higher levels of student debt were more likely to drop out of college than women with similar amounts of debt. The authors suggest that women’s labor market opportunities — often more likely to require college degrees than men’s — may account for these differences. McMillan Cottom’s interviews with 109 students from for-profit colleges uncovers how Black, low-income women in particular bear the burden of student loans. For many of these women, the rewards of college credentials outweigh the risks of high student loan debt.

- Rachel E. Dwyer, Randy Hodson, and Laura McCloud. 2013. “Gender, Debt, and Dropping Out of College.” Gender & Society 27(1): 30-55.

- Tressie McMillan Cottom. 2017. Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy. New York: The New Press.