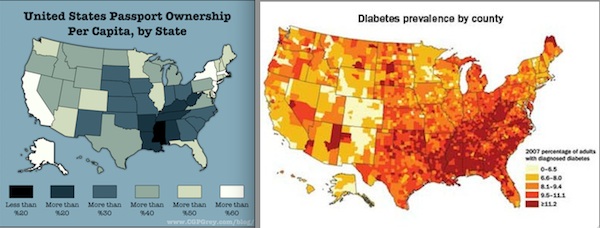

Dolores R. sent along an illustration of the nature of spurious relationships. A spurious relationship is one in which two variables appear to be related, but are in fact both caused by a third, “confounding” variable. Drawing on Andrew Sullivan’s map of passport ownership and data on Type 2 diabetes posted at the US News and World Report, Mark Frauenfelder at BoingBoing suggested, with tongue-in-cheek, that owning a passport prevents Type 2 diabetes. In fact, both are probably related to a third variable, class: having the money to travel also usually means having access to healthy foods and sufficient health insurance.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.