Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

The magic of demographic knowledge is a memorable moment in John Sayles’s 1984 movie “Brother From Another Planet.” On the A train, a young man shows an elaborate card trick to the title alien, who looks like an African American but seems to have no understanding of the trick. So the magician offers another.

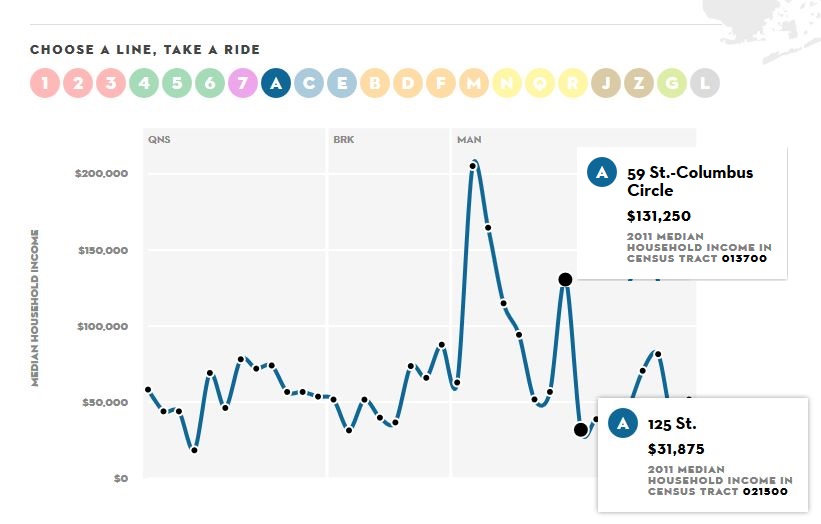

From 59th St. to 125th St. is one stop on the express. But as the movie shows, that short ride covers a large demographic change, and it’s not just racial. The New Yorker has posted interactive graphics showing the median income of the census tracts surrounding subway stations.

Take the A train one stop — from the southern border of Central Park to a few blocks above its northern border — and see median income drop by $100,000.

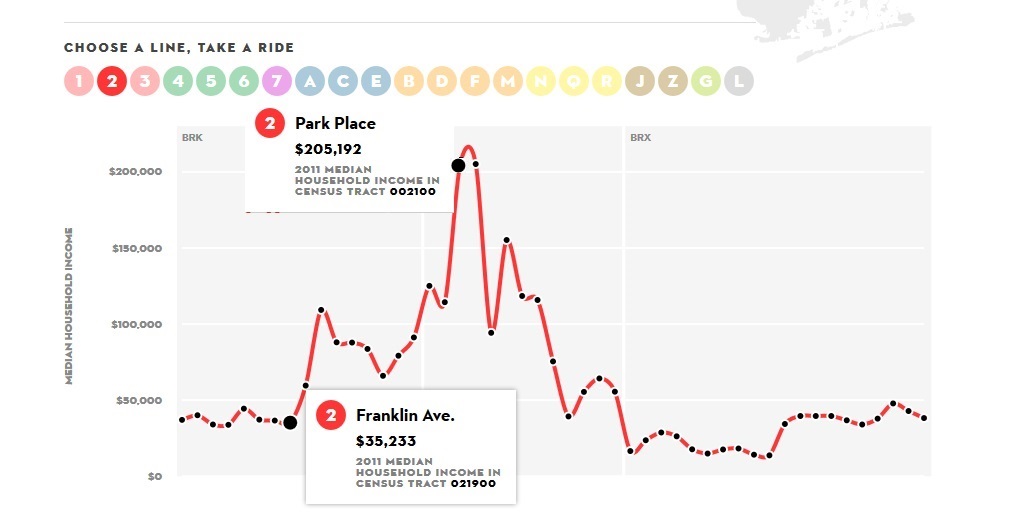

Many other lines travel the extremes of economic inequality. My line is the 2:

In the early morning commute, I see blue collar workers in their hoodies or rough jackets and steel-toe boots next to well-dressed people reading The Wall Street Journal. They didn’t get on at the same stop. The people who live in and work in the Wall Street census tract, which includes Park Place, are not on the train. Here’s what their housing looks like:

And here is Franklin St., Brooklyn:

The subway demographic trick is not limited to New York. Here’s a time-lapse video of the Red Line of Chicago’s CTA.

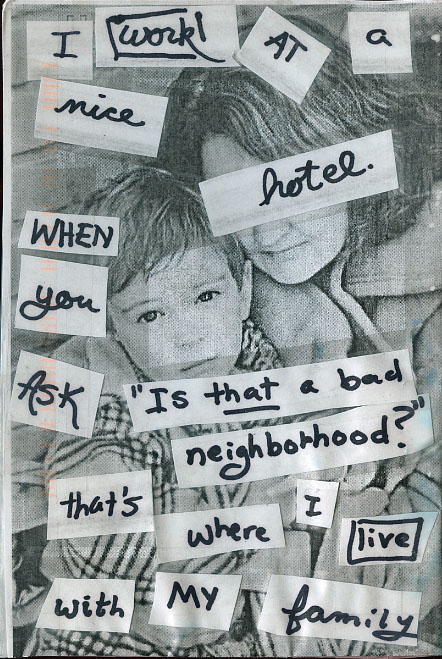

Despite the social class segregation in housing, in cities like New York and Chicago, people of vastly different economic circumstances are likely to share the same subway car, at least for a few stops. Yet I don’t get a sense of strong resentment or even envy among the have-nots (though I wish I had systematic data on this). This is similar to the findings of Rachel Sherman, who studied how workers at high-end hotels thought of their guests.

New York and Chicago, however, are also where the rich are more likely to be liberal and in favor of redistributionist policies. As Andrew Gelman has shown, the wealthy in rich states are far more liberal than the wealthy in poor states. That may be partly because in rich states, the wealthy live in the large cities. It would be interesting to see if we saw the same effect if we looked at Upstate New York, Downstate Illinois, or Massachusetts outside Rte. 128.

HT: Jenn Lena for the link.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.