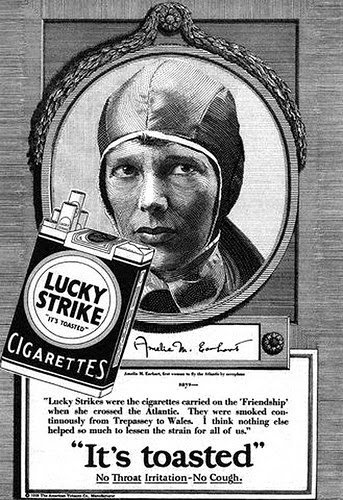

Hat tip to x-ray delta one, via Copyranter.

NEW! (Dec. ’09): Larry (of The Daily Mirror) found two images of Earhart from 1937 in the L.A. Times photo archives. In both Earhart was asked to pose in flirty or cutesy ways that it’s hard to imagine a famous male pilot being posed in:

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.