While it seems that much of the discourse around curbing gun violence focuses on the need to keep guns out of the hands of the mentally ill, these two issues — gun violence and mental illness — “intersect only at their edges.” These are the words of Jeffrey Swanson and his colleagues in their new article examining the personality characteristics of American gun owners.

To think otherwise, they argue, is to fall prey to the narrative of gun rights advocates, who want us to think that “controlling people with serious mental illness instead of controlling firearms is the key policy answer.” Since the majority of people with mental illnesses are never violent, this is unlikely to be an effective strategy while, at the same time, further stigmatizing people with mental illness.

What is a good strategy, then, short of the unlikely event that we take America’s guns away?

Swanson and colleagues argue that a better policy would be to look for signs of impulsive, angry, and aggressive behavior and limit gun rights based on that. Evidence of such behavior, they believe, “conveys inherent risk of aggressive or violent acts” substantial enough to justify limiting gun ownership.

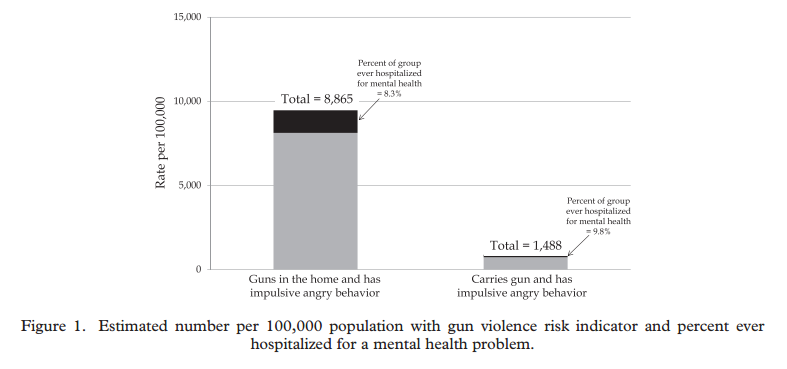

Using a nationally representative data set, they estimate that 8,865 people out of every 100,000 both (1) owns at least one gun and (2) exhibits impulsive angry behavior: angry outbursts, smashing things in anger, or losing their temper and engaging in physical fights. If I do my math right, that’s almost 22 million American adults (~321,300,000 people minus the 23% under 18 divided by 100,000 and multiplied by 8,865).

1,488 out of those 100,000, or almost 3.6 million, also carries a gun outside the home. People who owned lots of guns (six or more) were four times as likely to both have anger issues and carry outside the home.

The numbers of angry and impulsive people who own and carry guns, importantly, far exceeds the number of people who have been hospitalized for mental illness. This is a dangerous population, in other words, much larger than the one currently excluded from legal gun ownership.

“It is reasonable to imagine,” Swanson and his colleagues conclude, that people who are angry, aggressive, and impulsive have an arrest history. Accordingly, they advocate gun restrictions based on indicators of this personality type, such as convictions for misdemeanor violence, DUIs, and restraining orders. This, they think, would do a much better job of reducing gun violence than a focus on certified mental illness.

H/t to gin and tacos. Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.