It seems certain that the political economy textbooks of the future will include a chapter on the experience of Greece in 2015.

It seems certain that the political economy textbooks of the future will include a chapter on the experience of Greece in 2015.

On July 5, 2015, the people of Greece overwhelmingly voted “NO” to the austerity ultimatum demanded by what is colloquially being called the Troika, the three institutions that have the power to shape Greece’s future: the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund, and the European Central Bank.

The people of Greece have stood up for the rights of working people everywhere.

Background

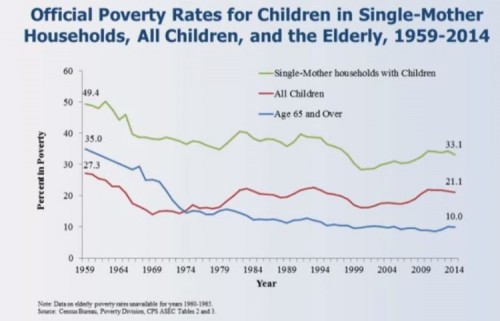

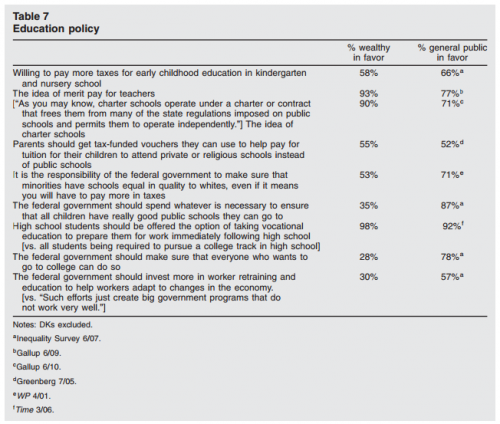

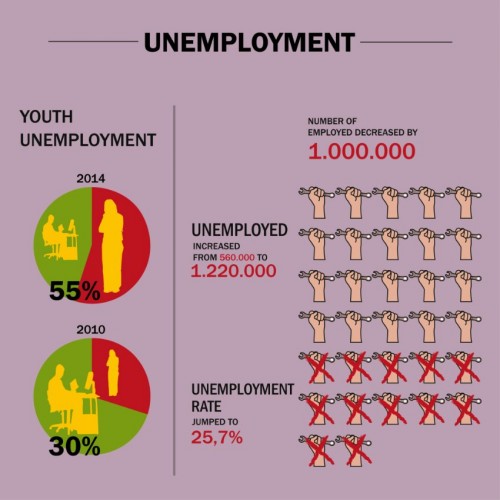

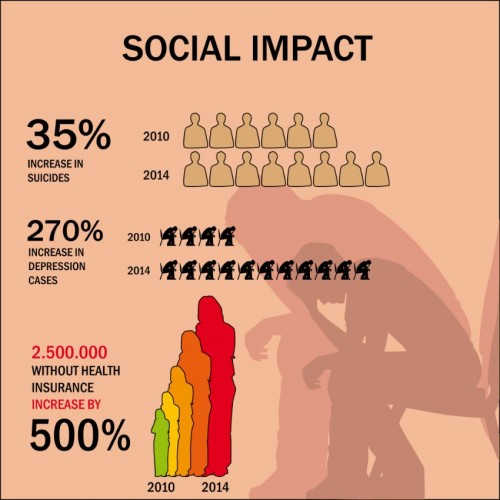

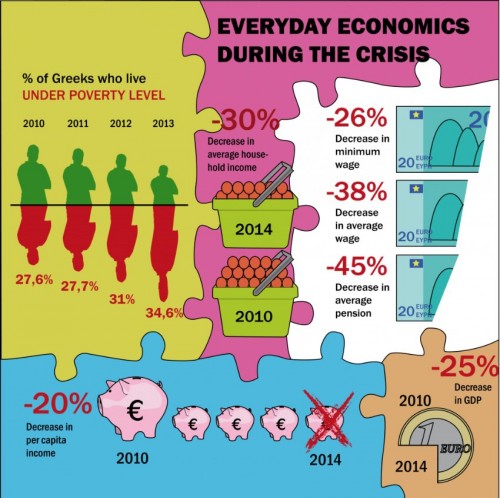

Greece has experienced six consecutive years of recession and the social costs have been enormous. The following charts provide only the barest glimpse into the human suffering:

While the Troika has been eager to blame this outcome on the bungling and dishonesty of successive Greek governments and even the Greek people, the fact is that it is Troika policies that are primarily responsible. In broad brush, Greece grew rapidly over the 2000s in large part thanks to government borrowing, especially from French and German banks. When the global financial crisis hit in late 2008, Greece was quickly thrown into recession and the Greek government found its revenue in steep decline and its ability to borrow sharply limited. By 2010, without its own national currency, it faced bankruptcy.

Enter the Troika. In 2010, they penned the first bailout agreement with the Greek government. The Greek government received new loans in exchange for its acceptance of austerity policies and monitoring by the IMF. Most of the new money went back out of the country, largely to its bank creditors. And the massive cuts in public spending deepened the country’s recession.

By 2011 it had become clear that the Troika’s policies were self-defeating. The deeper recession further reduced tax revenues, making it harder for the Greek government to pay its debts. Thus in 2012 the Troika again extended loans to the Greek government as part of a second bailout which included . . . wait for it . . . yet new austerity measures.

Not surprisingly, the outcome was more of the same. By then, French and German banks were off the hook. It was now the European governments and the International Monetary Fund that worried about repayment. And the Greek economy continued its downward ascent.

Significantly, in 2012, IMF staff acknowledged that the its support for austerity in 2010 was a mistake. Simply put, if you ask a government to cut spending during a period of recession you will only worsen the recession. And a country in recession will not be able to pay its debts. It was a pretty clear and obvious conclusion.

But, significantly, this acknowledgement did little to change Troika policies toward Greece.

By the end of 2014, the Greek people were fed up. Their government had done most of what was demanded of it and yet the economy continued to worsen and the country was deeper in debt than it had been at the start of the bailouts. And, once again, the Greek government was unable to make its debt payments without access to new loans. So, in January 2015 they elected a left wing, radical party known as Syriza because of the party’s commitment to negotiate a new understanding with the Troika, one that would enable the country to return to growth, which meant an end to austerity and debt relief.

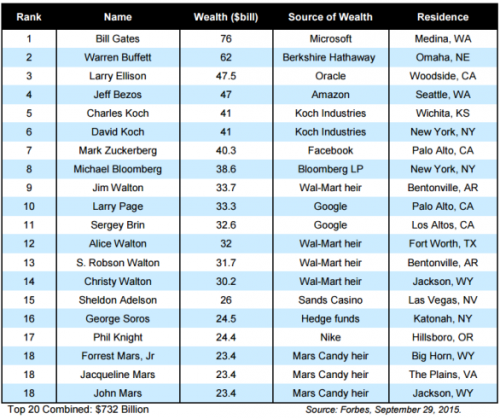

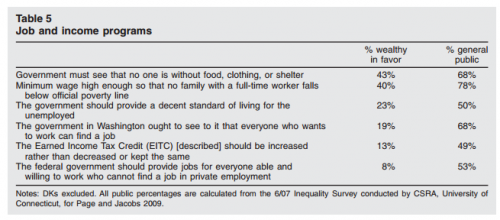

Syriza entered the negotiations hopeful that the lessons of the past had been learned. But no, the Troika refused all additional financial support unless Greece agreed to implement yet another round of austerity. What started out as negotiations quickly turned into a one way scolding. The Troika continued to demand significant cuts in public spending to boost Greek government revenue for debt repayment. Greece eventually won a compromise that limited the size of the primary surplus required, but when they proposed achieving it by tax increases on corporations and the wealthy rather than spending cuts, they were rebuffed, principally by the IMF.

The Troika demanded cuts in pensions, again to reduce government spending. When Greece countered with an offer to boost contributions rather than slash the benefits going to those at the bottom of the income distribution, they were again rebuffed. On and on it went. Even the previous head of the IMF penned an intervention warning that the IMF was in danger of repeating its past mistakes, but to no avail.

Finally on June 25, the Troika made its final offer. It would provide additional funds to Greece, enough to enable it to make its debt payments over the next five months in exchange for more austerity. However, as the Greek government recognized, this would just be “kicking the can down the road.” In five months the country would again be forced to ask for more money and accept more austerity. No wonder the Greek Prime Minister announced he was done, that he would take this offer to the Greek people with a recommendation of a “NO” vote.

The Referendum

Almost immediately after the Greek government announced its plans for a referendum, the leaders of the Troika intervened in the Greek debate. For example, as the New York Times reported:

By long-established diplomatic tradition, leaders and international institutions do not meddle in the domestic politics of other countries. But under cover of a referendum in which the rest of Europe has a clear stake, European leaders who have found [Greece Prime Minister] Tsipras difficult to deal with have been clear about the outcome they prefer.

Many are openly opposing him on the referendum, which could very possibly make way for a new government and a new approach to finding a compromise. The situation in Greece, analysts said, is not the first time that European politics have crossed borders, but it is the most open instance and the one with the greatest potential effect so far on European unity…

Martin Schulz, a German who is president of the European Parliament, offered at one point to travel to Greece to campaign for the “yes” forces, those in favor of taking a deal along the lines offered by the

creditors.

On Thursday, Mr. Schulz was on television making clear that he had little regard for Mr. Tsipras and his government. “We will help the Greek people but most certainly not the government,” he said.

European leaders actively worked to distort the terms of the referendum. Greeks were voting on whether to accept or reject Troika austerity policies yet the Troika leaders falsely claimed the vote was on whether Greece should remain in the Eurozone. In fact, there is no mechanism for kicking a country out of the Eurozone and the Greek government was always clear that it was not seeking to leave the zone.

Having whipped up popular fears of an end to the euro, some Greeks began talking their money out of the banks. On June 28, the European Central Bank then took the aggressive step of limiting its support to the Greek financial system.

This was a very significant and highly political step. Eurozone governments do not print their own money or control their own monetary systems. The European Central Bank is in charge of regional monetary policy and is duty bound to support the stability of the region’s financial system. By limiting its support for Greek banks it forced the Greek government to limit withdrawals which only worsened economic conditions and heightened fears about an economic collapse. This was, as reported by the New York Times, a clear attempt to influence the vote, one might even say an act of economic terrorism:

Some experts say the timing of the European Central Bank action in capping emergency funding to Greek banks this week appeared to be part of a campaign to influence voters.

“I don’t see how anybody can believe that the timing of this was coincidence,” said Mark Weisbrot, an economist and a co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington. “When you restrict the flow of cash enough to close the banks during the week of a referendum, this is a very deliberate move to scare people.”

Then on July 2, three days before the referendum, an IMF staff report on Greece was made public. Echos of 2010, the report made clear that Troika austerity demands were counterproductive. Greece needed massive new loans and debt forgiveness. The Bruegel Institute, a European think tank, offered a summary and analysis of the report, concluding that “the creditors negotiated with Greece in bad faith” and used “indefensible economic logic.”

The leaders of the Troika were insisting on policies that the IMF’s own staff viewed as misguided. Moreover, as noted above, European leaders desperately but unsuccessfully tried to kill the report. Only one conclusion is possible: the negotiations were a sham.

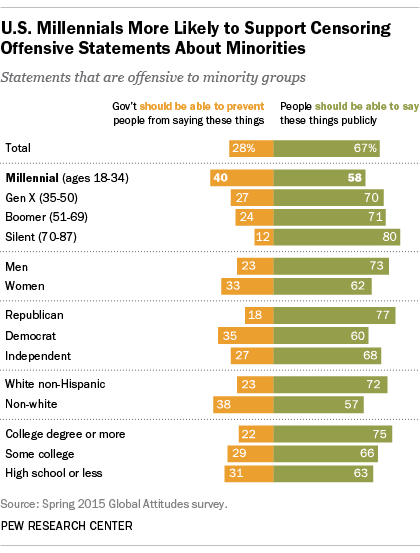

The Troika’s goals were political: they wanted to destroy the leftist, radical Syriza because it represented a threat to a status quo in which working people suffer to generate profits for the region’s leading corporations. It apparently didn’t matter to them that what they were demanding was disastrous for the people of Greece. In fact, quite the opposite was likely true: punishing Greece was part of their plan to ensure that voters would reject insurgent movements in other countries, especially Spain.

The Vote

And despite, or perhaps because of all of the interventions and threats highlighted above, the Greek people stood firm. As the headlines of a Bloomberg news story proclaimed: “Varoufakis: Greeks Said ‘No’ to Five Years of Hypocrisy.”

The Greek vote was a huge victory for working people everywhere.

Now, we need to learn the lessons of this experience. Among the most important are: those who speak for dominant capitalist interests are not to be trusted. Our strength is in organization and collective action. Our efforts can shape alternatives.

Cross-posted at Reports from the Economic Front.

Martin Hart-Landsberg is a professor of economics at Lewis and Clark College. You can follow him at Reports from the Economic Front.