We often think that as long as a white person doesn’t fly the Confederate flag, use the n-word, or show up to a white supremacist rally that they aren’t racist. However, researchers at Harvard and the Ohio State University, among others, have shown that even whites who don’t endorse racist beliefs tend to be biased against non-whites. This bias, though, is implicit: it’s subconscious and activated in decisions we make that are faster than our conscious mind can control.

You can test your own implicit biases here. Millions of people have.

But where do these negative subconscious attitudes come from? And when do they start?

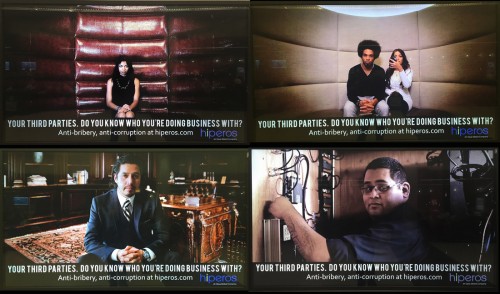

The Kirwan Institute for the study of race and ethnicity has found that we learn them early and often from the mass media. As an example, consider this seemingly harmless digital billboard for Hiperos, a company that works to protect clients against risk online. The ad implies that, as a business, you need to be leery of working with third parties. Of particular risk is exposure to bribery or corruption. Whom can you trust? Who are the people you should be afraid of? Who might be corrupt?

I took a photo of each of the ads as they cycled through. Turns out, the company portrays people you should be worried about as mostly non-white or not-quite-white.

Who is untrustworthy? Those that seem exotic: brown people, black people, Asian people, Latinos, Italian “mobsters,” foreigners.

There were comparatively few non-Hispanic whites represented:

Of course, this company’s advertising alone could not powerfully influence whom we consider suspicious, but stuff like this — combined with thousands of other images in the news, movies, and television shows — sinks into our subconscious, teaching us implicitly to fear some kinds of people and not others.

For more, see the original post on sociologytoolbox.com.

Todd Beer, PhD is an Assistant Professor at Lake Forest College, a liberal arts college north of Chicago. His blog, SOCIOLOGYtoolbox, is a collection of tools and resources to help instructors teach sociology and build an active sociological imagination.