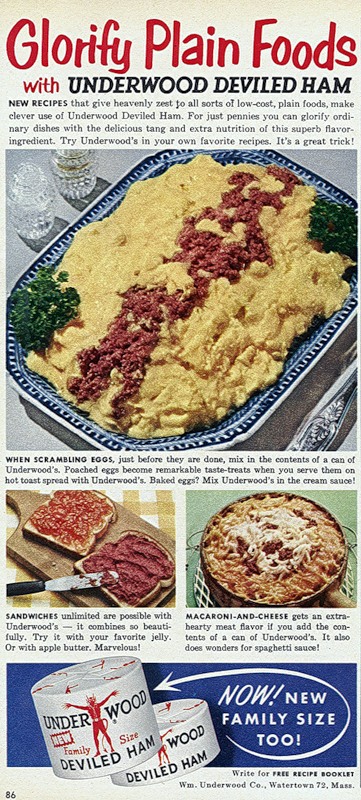

The vintage ad below is another great example of how “tasty” is socially constructed (i.e., culturally- and historically-contingent). If I’m not mistaken, this ad for canned deviled ham is suggesting that it makes a great sandwich when combined with jelly:

For more fun food-related examples of social construction, see our posts on meat-flavored gelatin, savory veggie jell-o, vitamin beer, cucumber flavored soda, soup for breakfast, and 7Up milk.

Source: Vintage Ads.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.