@zeyneparsel and Stephanie S. both sent in a link to a new craze in China: peach panties. I totally made the craze part up — I have no idea about that — but the peach panties are real and there is a patent pending.

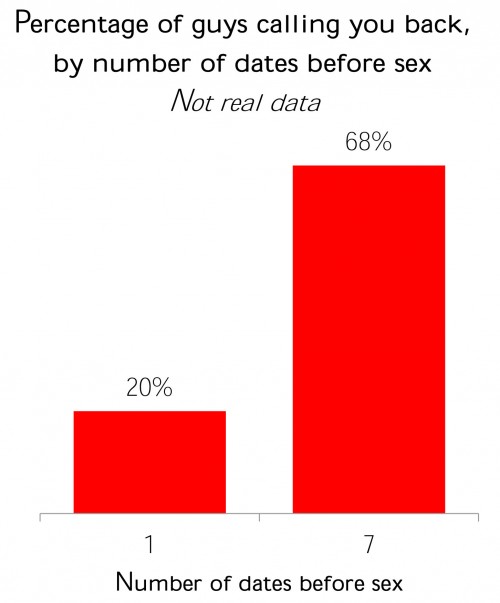

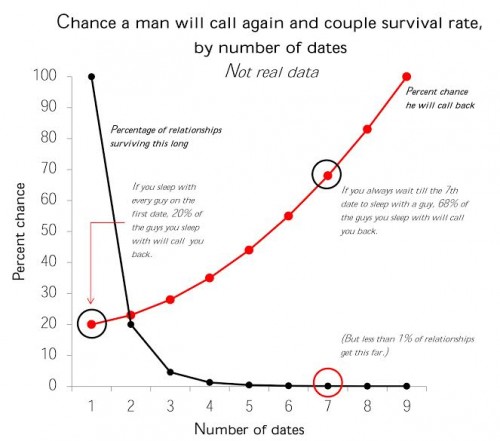

I thought they were a great excuse to make a new Pinterest board featuring examples of marketing that uses sex to sell decidely unsexy — or truly sex-irrelevant — things. It’s called Sexy What!? and I describe it as follows:

This board is a collection of totally random stuff being made weirdly and unnecessarily sexual by marketers who — I’m gonna say it — have run out of ideas.

My favorites are the ads for organ donation, hearing aids, CPR, and sea monkeys. Enjoy!

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.