America woke up this weekend to the news of the Orlando massacre, the deadliest civilian mass shooting in the nation’s history. The senseless tragedy will undoubtedly evoke anger, sadness and helplessness.

America woke up this weekend to the news of the Orlando massacre, the deadliest civilian mass shooting in the nation’s history. The senseless tragedy will undoubtedly evoke anger, sadness and helplessness.

In the meantime, many will forget to think and talk about Stanford swimmer Brock Turner’s crime and his “summer vacation” jail sentence: three months for the vile sexual assault of an unconscious woman.

As a sociologist, I was struck not by the abrupt shift to a new moral crisis, but by the continuity. Sociologists look for the bigger picture, and in my mind, Mateen’s crime didn’t displace Turner’s. Yet the media simply replaced one outrage with another, moving our attention away from Stanford and toward Orlando, as if these two crimes were unrelated. They’re not.

Status, masculinity and sexual assault

Brock Turner was an all-American boy: a white, Division I swimmer at one of the nation’s top universities. What he did to his victim was arguably all-American, too, confirmed by decades of research tying rape to a sense of male superiority and entitlement.

I study sex on campus, where sexual violence is perpetrated disproportionately by “high-status” men – fraternity men and certain male athletes in particular. These men are more likely than other men to endorse the sexual double standard, believing that they are justified in praising sexually active men, while condemning and even abusing women who are less sexually active.

They are also more likely to promote homophobia, hypermasculinity and male dominance; tolerate violent and sexist jokes; endorse misogynistic attitudes and behaviors; and endorse false beliefs about rape. Accordingly, athletes are responsible for an outsized number of sexual assaults on campus, and women who attend fraternity parties are significantly more likely to be assaulted than those who attend other parties with alcohol and those who don’t go to parties at all.

Status, masculinity and violent homophobia

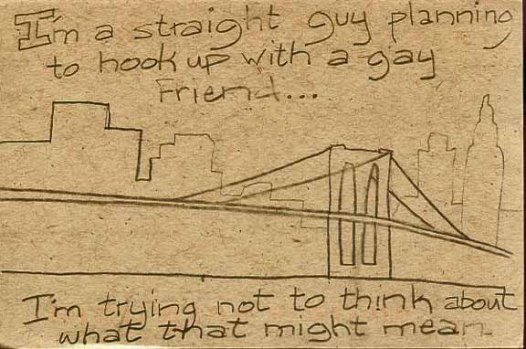

Omar Mateen’s crime is related to this strand of masculinity. Mateen’s father told the media that his son had previously been angered by the sight of two men kissing, and reports claim that he was a “regular” at the Pulse nightclub and was known to use a gay hookup app.

Anti-gay hate crimes, like violence against women (Mateen also reportedly beat his ex-wife), are tied closely to rigid and hierarchical ideas about masculinity that depend on differentiating “real” men from women as well as gay and bisexual men. Men who experience homoerotic feelings themselves sometimes erupt into especially aggressive homophobia.

As the sociologist Michael Kimmel has argued, while we talk ad infinitum about guns, mental illness and, in this case, Islamic identity, we miss the strongest unifying factor: these mass murderers are men, almost to the last one. In his book “Guyland,” Kimmel argues that as many boys grow into men, “they learn that they are entitled to feel like a real man, and that they have the right to annihilate anyone who challenges that sense of entitlement.”

He means “annihilate” literally.

We now know that many boys who descend on their schools with guns are motivated by fears that they are perceived as homosexual and that attacking suspected or known homosexuals is a way for boys to demonstrate heterosexuality to their peers.

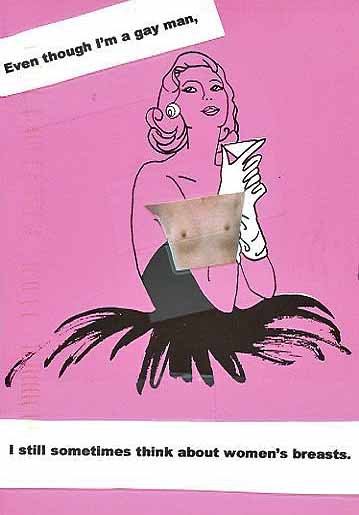

It makes sense to me, as a woman, that men would fear gay men because such men threaten to put other men under the same sexually objectifying, predatory, always potentially threatening gaze that most women learn to live with as a matter of course. Being looked at by a gay man threatens to turn any man into a figurative woman: subordinate, weak, penetrable. That can be threatening enough to a man invested in masculinity, but discovering that he enjoys being the object of other men’s desires – being put in the position of a woman – could stoke both internalized and externalized homophobia even further.

Meanwhile, gay men, by their very existence, challenge male dominance by undermining the link between maleness and the sexual domination of women. It’s possible that Mateen, enraged by his inability to stop men from kissing in public and struggling with self-hatred, took it upon himself to annihilate the people who dared pierce the illusion that manhood and the righteous sexual domination of women naturally go hand-in-hand.

The common denominator

Mass shootings, frighteningly, appear to have become a part of our American cultural vernacular, a shared way for certain men to protest threats to their entitlement and defend the hierarchy their identities depend on. As the sociologists Tristan Bridges and Tara Leigh Tober wrote last year for the website Feminist Reflections:

This type of rampage violence happens more in the United States of America than anywhere else… Gun control is a significant part of the problem. But, gun control is only a partial explanation for mass shootings in the United States. Mass shootings are also almost universally committed by men. So, this is not just an American problem; it’s a problem related to American masculinity and to the ways American men use guns.

Some members of the media and candidates for higher office will focus exclusively on Mateen’s Afghan parents. But he – just like Brock Turner – was born, raised and made a man right here in America. While it appears that he had (possibly aspirational) links to ISIS, it in no way undermines his American-ness. This was terrorism, yes, but it was domestic terrorism: of, by and aimed at Americans.

I don’t want to force us all to keep Turner in the news (though I imagine that he and his father are breathing a perverse sigh of relief right now). I want to remind us to keep the generalities in mind even as we mourn the particulars.

Sociologists are pattern seekers. This problem is bigger than Brock Turner and Omar Mateen. It’s Kevin James Loibl, who sought out and killed the singer Christina Grimmie the night before the massacre at Pulse. It’s James Wesley Howell, who was caught with explosives on his way to the Los Angeles Pride Parade later that morning. It’s the grotesque list of men who used guns to defend their sense of superiority that I collected and documented last summer.

The problem is men’s investment in masculinity itself. It offers rewards only because at least some people agree that it makes a person better than someone else. That sense of superiority is, arguably, why men like Turner feel entitled to violating an unconscious woman’s body and why ones like Mateen will defend it with murderous rampages, even if it means destroying themselves in the process. And unless something changes, there will be another sickening crisis to turn to, and another sinking sense of familiarity.

Cross-posted at The Conversation, New Republic, Special Broadcasting Company (SBS), United Press International, Newsweek Japan (in Japanese), and Femidea (in Korean).

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.