This Sunday is the 2012 Oscars ceremony. The Oscars are awarded based on the votes of nearly 6,000 members of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; however, the Academy keeps the identities of the voting members secret, so there’s little knowledge of who, exactly, determines the recipients of Oscars, prestigious awards within the industry that can increase interest in a film, increase job opportunities, and generally raise the profile of winners.

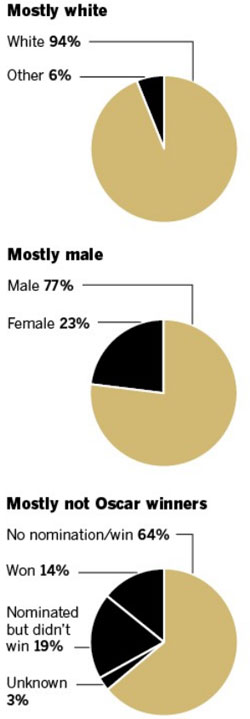

Sangyoub Park sent in a link to an article at the L.A. Times story about Academy voters. Times reporters were able to verify the identity of 89% of current voters, and the paper provided this breakdown of their demographics; as it turns out, those deciding who wins an Oscar are overwhelmingly White non-Hispanic and male:

Within some categories of voting members, Whites are even more dominant; they make up 98% of writers and executives. Voters are also disproportionately older; the median age is 62, and the Times reports that only 14% were under age 50.

As the Times story illustrates, many inside and outside of the film industry believe the make-up of Oscar voters influences which movies, actors, and directors have a serious chance of winning, with those that appeal to middle-aged White men inherently advantaged because of the lack of diversity among voters.