A new study tackles the media landscape building up to the election. The lead investigator, Rob Faris, runs a center at Harvard that specializes in the internet and society. He and his co-authors asked what role partisanship and disinformation might have played in the 2016 U.S. election. The study looked at links between internet news sites and also the behavior of Twitter and Facebook users, so it paints a picture of how news and opinion is being produced by media conglomerates and also how individuals are using and sharing this information.

They found severe ideological polarization, something we’ve known for some time, but also asymmetry in how media production and consumption works on either side. That is, journalists and readers on the left are behaving differently from those on the right.

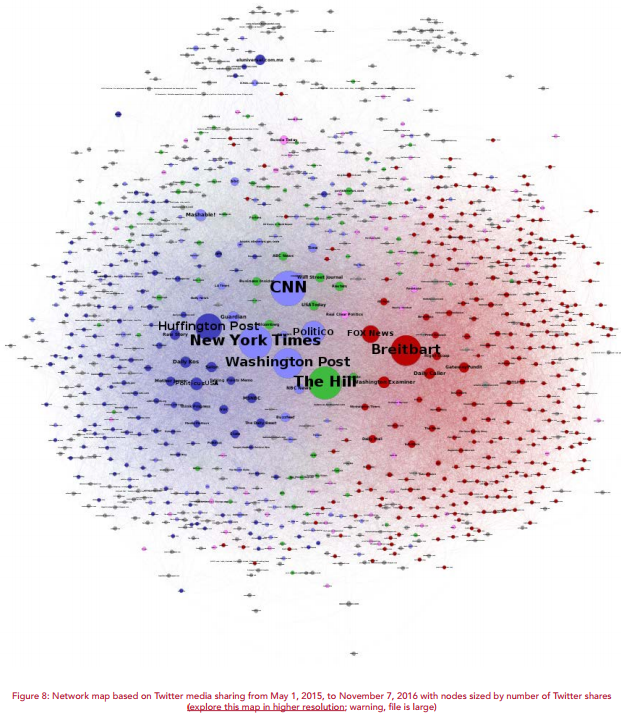

The right is more insular and more partisan than the left: conservatives consume less neutral and “other side” news than liberals do and their outlets are more aggressively partisan. Breitbart News now sits neatly at the center. Measured by inlinks, it’s as influential as FOX News and, on social media, substantially more. Here’s the network map for Twitter:

Breitbart’s centrality on the right is a symptom of how extreme the Republican base has become. Breitbart’s Executive Chairman, Steve Bannon — former White House Chief Strategist — calls it “home of the alt-right,” a group that shows “extreme” bias against racial minorities and other out-groups.

The insularity and lack of interest in balanced reporting made right-leaning readers susceptible to fake stories. Faris and his colleagues write:

The more insulated right-wing media ecosystem was susceptible to sustained network propaganda and disinformation, particularly misleading negative claims about Hillary Clinton. Traditional media accountability mechanisms — for example, fact-checking sites, media watchdog groups, and cross-media criticism — appear to have wielded little influence on the insular conservative media sphere.

There is insularity and partisanship on the left as well, but it is mediated by commitments to traditional journalistic norms — e.g., covering “both sides” — and so, on the whole, the left got more balance in their media diet and less “fake news” because they were more friendly to fact checkers.

The interest in balance, however, perhaps wasn’t entirely good. Faris and his co-authors found that the right exploited the left’s journalistic principles, pushing left-leaning and neutral media outlets to cover negative stories about Clinton by claiming that not doing so was biased. Centrist media outlets responded with coverage, but didn’t ask the same of the right (it is possible this shaming tactic wouldn’t have worked the other way).

The take home message is: During the 2016 election season, right-leaning media consumers got rabid, un-fact checked, and sometimes false anti-Clinton and pro-Trump material and little else, while left-leaning media consumers got relatively balanced coverage of Clinton: both good stories and bad ones, but more bad ones than they would have gotten (for better or worse) if the right hadn’t been yanking their chain about being “fair.”

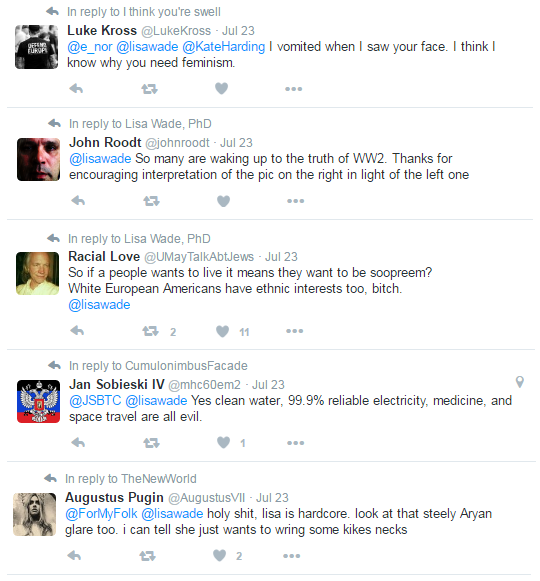

We should be worried about how polarization, “fake news,” horse-race journalism, and infotainment are influencing the ability of voters to gather meaningful information with which to make voting decisions, but the asymmetry between the left and the right media sphere — particularly how it makes the right vulnerable to propagandists and the left vulnerable to ideological bullying by the right — should leave us even more worried. These are powerful forces, held up both by the institutions and the individuals, that are dramatically skewing election coverage, undermining democracy, and throwing elections, and governance itself, to the right.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

In his speech accepting the Republican nomination for President, Donald Trump

In his speech accepting the Republican nomination for President, Donald Trump