Cross-posted at Racialicious.

Frances Stead Sellers at the Washington Post has a fascinating account of the differences in Black and White American sign language. Sellers profiles a 15-year-old girl named Carolyn who in 1968 was transferred from the Alabama School for the Negro Deaf and Blind to an integrated school, only to learn that she couldn’t understand much of what was being signed in class.

White American sign language used more one-handed signs, a smaller signing space, stayed generally lower, and included less repetition. Some of the signs were subtlety different, while others were significantly different.

As is typical, the White students in the class did not adapt to Carolyn’s vernacular; she had to learn theirs. So she became bilingual. Sellers explains:

She learned entirely new signs for such common nouns as “shoe” and “school.” She began to communicate words such as “why” and “don’t know” with one hand instead of two as she and her black friends had always done. She copied the white students who lowered their hands to make the signs for “what for” and “know” closer to their chins than to their foreheads. And she imitated the way white students mouthed words at the same time as they made manual signs for them.

Whenever she went home, [Carolyn] carefully switched back to her old way of communicating.

These distinctions are still present today, as are the White-centric rules that led Carolyn to adopt White sign language in school and the racism that privileges White spoken vernacular as “proper English.” For example, referring to the way she uses more space when she signs, student Dominique Flagg explains:

People sometimes think I am mad or have an attitude when I am just chatting with my friends, professors and other people.

The little girl who transferred schools and discovered that White people signed differently than her is now Dr. McCaskill, a professor of deaf studies. You can learn more about the racial politics of American sign language from her book, The Hidden Treasure of Black ASL.

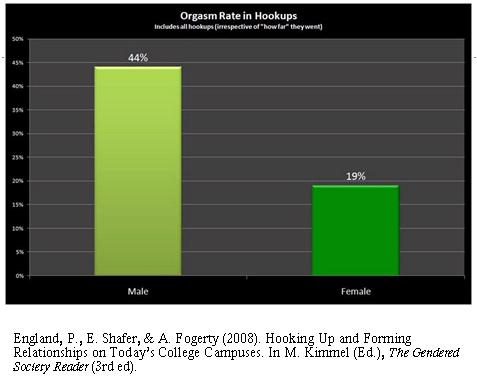

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.