Claude Fischer at Made in America offered some data speaking to the idea that Americans are especially patriotic. That they, in other words, are more likely than citizens of other nations to think that “We’re Number One!”

Fischer provides some evidence by Tom Smith at the International Social Science Programme (ISSP; Tom’s book). The ISSP, Fischer explains…

…involves survey research institutions in dozens of countries asking representative samples of their populations the same questions. A couple of times the ISSP has had its members ask questions designed to tap respondents’ pride in their countries… One set of questions asked respondents how much they agreed or disagreed with five statements such as “I would rather be a citizen of [my country] than of any other country in the world” and “Generally, speaking [my country] is a better country than most other countries.”

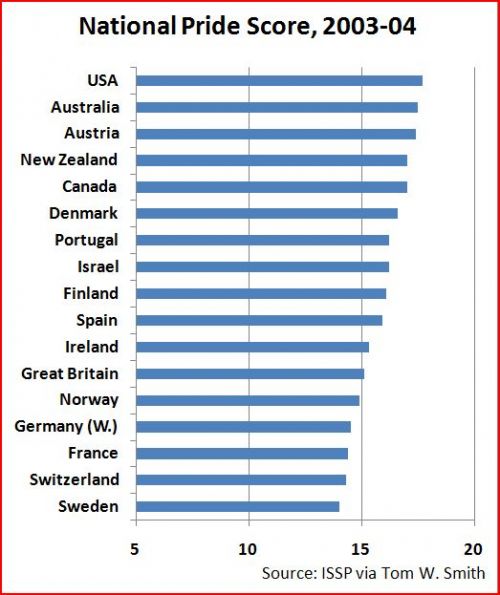

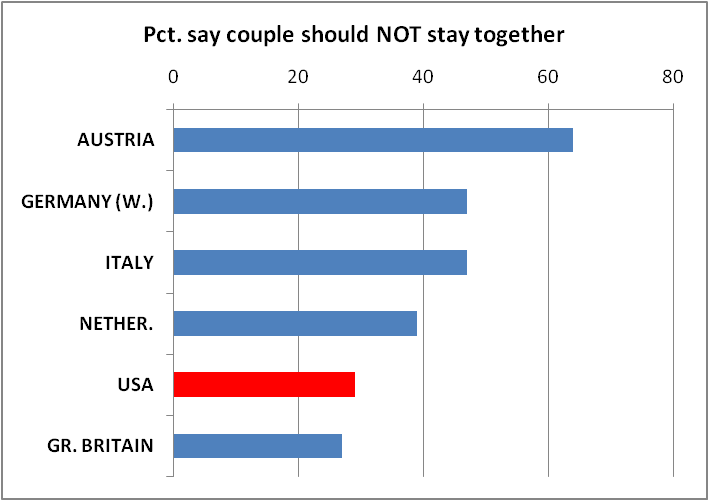

Smith put responses on a scale from 5 to 25, with 25 being the most patriotic. Here are the results from some of the affluent, western democracies (on a shortened scale of 5 to 20):

As Fischer says, “Americans were #1 in claiming to be #1.” Well, sort of. Americans were the most patriotic among this group. They turned out to be the second most patriotic of all countries. Venezuela beat us.

(In any case, what struck me wasn’t the fact that the U.S. is so patriotic, but that many other of these countries were very patriotic as well! The U.S. is certainly no outlier among this group. In fact, it looks like all of these countries fall between 14 and 18 on this 20-point scale. Statistically significant, perhaps, but how meaningful of a difference is it?)

Fischer goes on to ask what’s good and bad about pride and closes with the following concern for U.S. Americans:

We believe that we are #1 almost across the board, when in fact we are far below number one in many arenas – in health, K-12 education, working conditions, to mention just a few. Does our #1 pride then blind us to the possibility that we could learn a thing or two from other countries?

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.