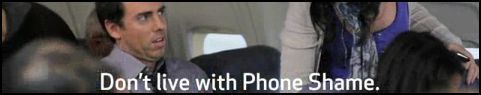

David Mayeda at The Grumpy Sociologist discussed a commercial, for Best Buy, encouraging us (men?) to feel embarrassed if we don’t have the most recent technology:

Mayeda sees this as an example of the making of deviance. He writes:

So, as a male, if you don’t have the financial capital to possess a kick ass phone, you are a deviant male, with a low-end job (sharing a cubicle), without technical prowess (can’t stay on top of your e-mail or access the net), and bottom line, you aren’t an attractive mate.

How far “behind” does a person need to “fall” before they are so “out of the loop” that they are not really part of respectable society anymore?

I have only had a cell phone myself for four short years. Yet, when I learn that someone doesn’t have one, the neurons in my brain short out a bit. How do two people even know each other if one doesn’t have a cell phone? How do you let someone know you’ve hit traffic? Find them in a crowded place? Cell phones have become so ubiquitous that not having one seems deliberately counter-cultural. Like face tattoos or men in skirts, eschewing a cell phone seems deviant indeed. So maybe Best Buy isn’t that far off the mark.

UPDATE DEC. 20, 2010: I failed to mention that, at the time of this post, I did not own a smart phone at all. Now I have joined the hip cats of the 21st century: I have a smart phone. Though, I would like to specify, that I was able to attract a mate without one. Then again, I am a chick, so how much money I can spend on a phone is slightly less important, or so I hear.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.