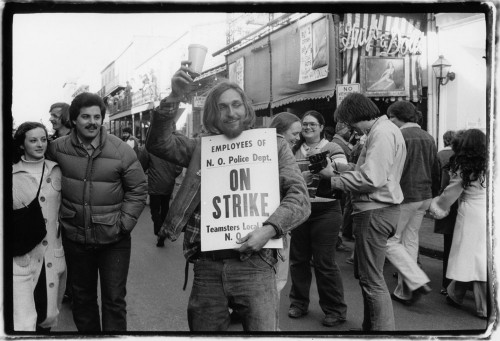

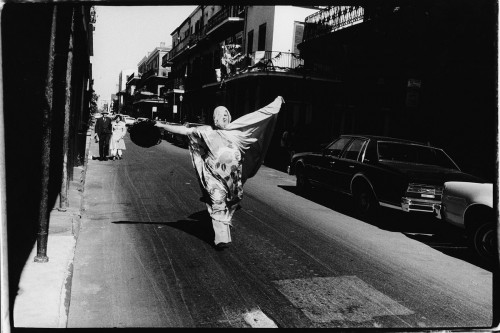

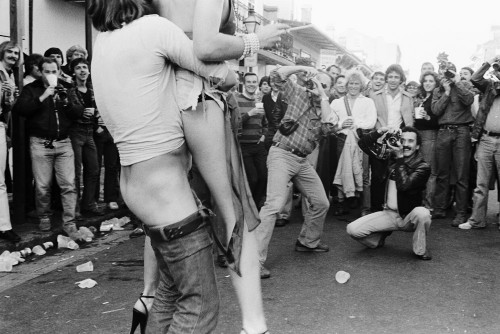

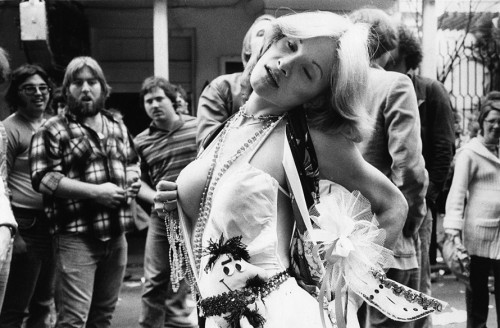

In 1979 the New Orleans police department went on strike, using the powerful leverage of Mardi Gras to push for an improvement in their working conditions. The city held fast and the celebration was cancelled. Ish. Some parades moved just out of town. Most tourists stayed away, fearful of unregulated reveling. But lots of locals went forward with the holiday, partying in the streets without the influx of tourists that accompany a typical Fat Tuesday.

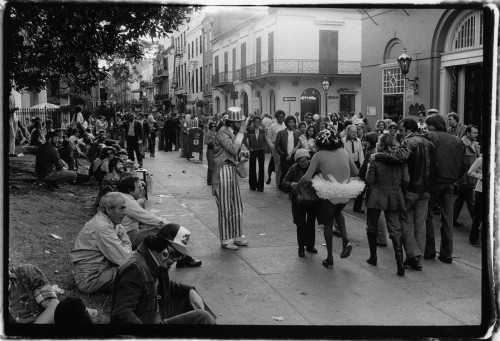

The National Guard was called in to ensure a semblance of order, but they ignored vice, intervening only against violence. According to Wikipedia, many French Quarter locals decided it was the best Mardi Gras ever. Photographer Robbie McClaran was there. Here are some of his photographs of the day:

Of the last photo, McClaran writes: “I remember this scene like it was yesterday, it was the moment when I thought to myself Mardis Gras had reached a level of surreality I had never experienced before. Homeless woman dancing with a man in a tutu while Uncle Sam looks on and salutes.”

Le bon temps roule, everybody.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.