The barbershop holds a special place in American culture. With its red, white, and blue striped poles, dark Naugahyde chairs, and straight razor shaves, the barbershop has been a place where men congregate to shore up their stubble and get a handle on their hair. From a sociological perspective, the barbershop is an interesting place because of its historically homosocial character, where men spend time with other men. In the absence of women, men create close relationships with each other. Some might come daily to talk with their barbers, discuss the news, or play chess. Men create community in these places, and community is important to people’s health and well-being.

But is the barbershop disappearing? If so, is anything taking its place?

In my study of high-service men’s salons — dedicated to the primping and preening of an all male clientele — hair stylists described the “old school” barbershop as a vanishing place. They explained that men are seeking out a pampered grooming experience that the bare bones barbershop with its corner dusty tube television doesn’t offer. The licensed barbers I interviewed saw these newer men’s salons as a “resurgence” of “a men-only place” that provides more “care” to clients than the “dirty little barbershop.” And those barbershops that are sticking around, said Roxy, one barber, are “trying to be a little more upscale.” She encourages barbers to “repaint and add flat-screen TVs.”

When I asked clients of one men’s salon, The Executive, if they ever had their hair cut at a barbershop, they explained that they did not fit the demographic. Barbershops, they said, are for old men with little hair to worry about or young boys who don’t have anyone to impress. As professional white-collar men, they see themselves as having outgrown the barbershop. A salon, with its focus on detailed haircuts and various services, including manicures, pedicures, hair coloring, and body waxing, help these mostly white men to obtain what they consider to be a “professional” appearance. “Professional men… they know that if they look successful, that will create connotations to their clients or customers or others that they work with — that they are smart, that they know what they’re doing,” said Gill, a client of the salon and vice-president in software, who reasoned why men go to the salon.

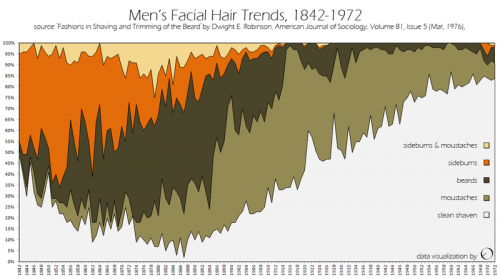

Indeed the numbers support the claim that barbershops are dwindling, and it may indeed be due to white well-to-do men’s shifting attitudes about what a barbershop is, what it can offer, and who goes there. (In my earlier research on a small women’s salon, one male client told me the barbershop is a place for the mechanic, or “grease-monkey,” who doesn’t care how he looks, and for “machismo” men who prefer a pile of Playboy magazines rather than the finery of a salon). According to Census data, there is a fairly steady decline in the number of barbershops over twenty years. From 1992-2012, we saw a 23% decrease in barbershops in the United Stated, with a slight uptick in 2013.

But these attitudes about the barbershop as a place of ol’, as a fading institution that provides outdated fades, is both a classed and raced attitude. With all the nostalgia for the barbershop in American culture, there is surprisingly little academic writing about it. It is telling, though, that research considering the importance of the barbershop in men’s lives focuses on black barbershops. The corner barbershop is alive and well in black communities and it serves an important role in the lives of black men. In her book, Barbershops, Bibles, and BET, political scientist and TV host, Melissa Harris-Perry, wrote about everyday barbershop talk as important for understanding collective efforts to frame black political thought. Scholars also find the black barbershop remains an important site for building communities and economies in black neighborhoods and for socializing young black boys.

And so asking if the barbershop is vanishing is the wrong question. Rather, we should be asking: Where and for whom is the barbershop vanishing? And where barbershops continue as staples of a community, what purpose do they serve? Where they are disappearing, what is replacing them, and what are the social relations underpinning the emergence of these new places?

In some white hipster neighborhoods, the barbershop is actually making a comeback. In his article, What the Barbershop Renaissance Says about Men, journalist and popular masculinities commentator, Thomas Page McBee, writes that these places provide sensory pleasures whereby men can channel a masculinity that existed unfettered in the “good old days.” The smell of talcum powder and the presence of shaving mugs help men to grapple with what it means to be a man at a time when masculinity is up for debate. But in a barbershop that charges $45 for a haircut, some men are left out. And so, in a place that engages tensions between ideas of nostalgic masculinity and a new sort of progressive man, we may very well see opportunities for real change fall by the wayside. The hipster phenomenon, after all, is a largely white one that appropriates symbols of white working-class masculinity: think white tank tops with tattoos or the plaid shirts of lumbersexuals.

When we return to neighborhoods where barbershops are indeed disappearing, and being replaced with high-service men’s salons like those in my book, Styling Masculinity, it is important to put these shifts into context. They are not signs of a disintegrating by-gone culture of manhood. Rather, they are part of a transformation of white, well-to-do masculinity that reflects an enduring investment in distinguishing men along the lines of race and class according to where they have their hair cut. And these men are still creating intimate relationships; but instead of immersing themselves in communities of men, they are often building confidential relationships with women hair stylists.

Kristen Barber, PhD is a sociologist at Southern Illinois University and the author of Styling Masculinity: Gender, Class, and Inequality in the Men’s Grooming Industry. She blogs at Feminist Reflections, where this post originally appeared.

*Thank you to Trisha Crashaw, graduate student at Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, for her work on the included graph.