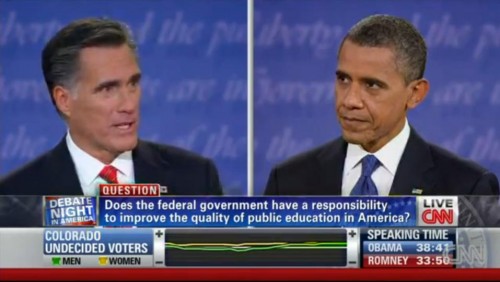

I watched the first U.S. Presidential debate of the election last night and I noticed something interesting about the coverage at CNN. Notice that the live viewer information along the bottom includes the degree to which female (yellow) and male (green) Colorado undecided voters like or dislike what each candidate is saying (measured by the middle bar).

By choosing to display data by gender, CNN gives us some idea of how men and women agree or disagree on their evaluations of the candidates, but it also makes gender seem like the most super-salient variable by which to measure support. They didn’t, for example, offer data on how upper and middle class undecided voters in Colorado perceived the debate, nor did they offer data on immigrant vs. non-immigrant, White vs. non-white, gay vs. straight, or any number of demographic variables they could have chosen from.

Instead, by promoting gender as the relevant variable, they also gave the impression that gender was the relevant variable. This makes it seem like men and women must be really different in their opinions (otherwise, why would they bother highlighting it), strengthening the idea that men and women are different and, even, at odds. In fact, men and women seemed to track each other pretty well.

It’s not that I don’t think gender is an interesting variable, it’s just that I don’t think it’s the only interesting one and making it seem so is problematic. I would have loved to have seen the data parsed in other ways too, perhaps by rotating what variables they highlighted. This would have at least given us a more nuanced view of public opinion (among undecided voters in Colorado) instead of reifying the same old binary.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.