Many important things will be said in the next few weeks about the murder of nine people holding a prayer meeting at a predominantly African American church yesterday. Assuming that Dylann Roof is the murderer and that he made the proclamation being quoted in the media, I want to say: “I am a white woman. No more murder in my name.”

Before gunning down a room full of black worshippers, Roof reportedly said:

I have to do it. You rape our women and you’re taking over our country. And you have to go.

For my two cents, I want to suggest that Roof’s alleged act was motivated by racism, first and foremost, but also sexism. In particular, a phenomenon called benevolent sexism.

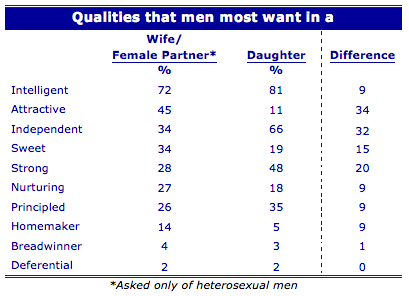

Sociologists use the term to describe the attribution of positive traits to women that, nonetheless, justify their subordination to men. For example, women may be described as good with people, but this is believed to make them perform poorly in competitive arenas like work, sports, or politics. Better that they leave that to the men. Women are wonderful with children, they say, but this is used to suggest that they should take primary responsibility for unpaid, undervalued domestic work. Better that they let men support them.

And, the one that Roof used to rationalize his racist act was: Women are beautiful, but their grace makes them fragile. Better that they stand back and let men defend them. This argument is hundreds of years old, of course. It’s most clearly articulated in the history of lynching in which black men were routinely violently murdered by white mobs using the excuse that they raped a white woman.

I stand with Jessie Daniel Ames and her “revolt against chivalry” in the 1920s and ’30s. Ames was one of the first white women to speak out against lynching, arguing that its rationale was sexist as well as racist. Roof is the modern equivalent of this white mob. He believes that he and other white men own me and women like me — “you rape our women,” he said possessively — and so he justified gunning down innocent black people on my behalf. You are vulnerable, he’s whispering to me, let me protect you.

All oppression is interconnected. The matrix of domination must come down. I am a white woman. No more murder in my name.

This essay was expanded for The Conversation and cross-posted at the Washington Post.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.