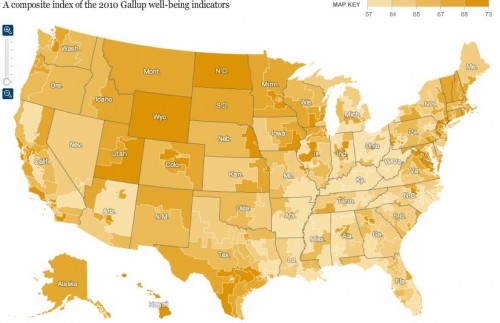

Kristina K. sent in a link to an interactive map at the New York Times that shows the results of Gallup’s 2010 polls of well-being. [UPDATE: Reader Danielle pointed out I forgot to provide a link to the map. Sorry! You can find it here.] Gallup surveys 1,000 people per day about a variety of indicators of well-being, including questions about physical, mental, and emotional health, various health-related behaviors, ability to access health care, access to adequate food and housing, and perceptions of their communities. Here are the overall composite scores, by congressional district (a higher score is better):

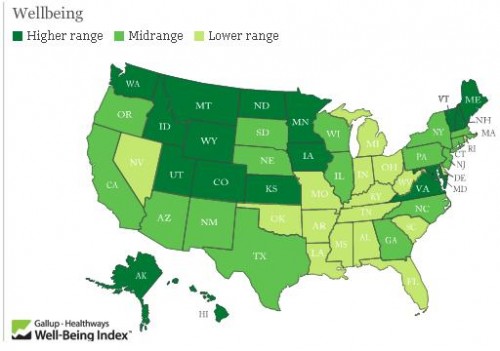

The general geographic pattern indicates a swath of relatively low well-being curving from Louisiana up through Michigan, while those in the upper Great Plains and the inter-mountain West are doing better than average.

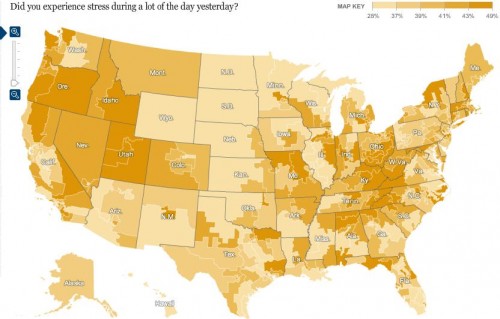

Percent reporting experiencing a lot of stress:

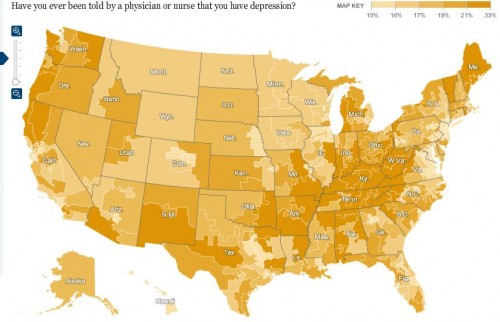

Percent who have ever been told they have depression:

Of course, this may reflect differences in rates of depression, but it could also reflect differences in medical professionals’ likelihood of identifying a set of symptoms as depression and bringing it up with a patient. For example, we see significant differences by state in the frequency of Caesarean sections among pregnant women.

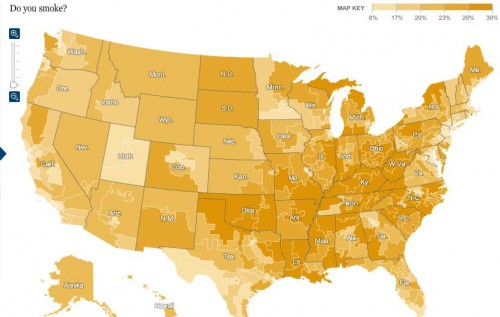

Percent of people who smoke:

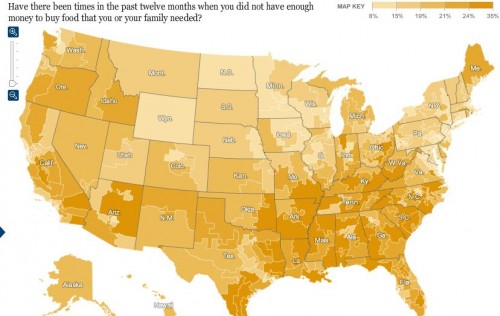

Percent reporting an inability to buy sufficient food:

The Gallup page on well-being presents more data. Here is a map of 2009 overall well-being that is a bit easier to read since it’s presented by state rather than congressional district:

Hawaii had the highest overall score, at 70.2; West Virginia had the lowest, 60.5. If you go to their site and click on a state, you can get a breakdown of scores in each area (emotional well-being, physical health, healthy behaviors, and so on).

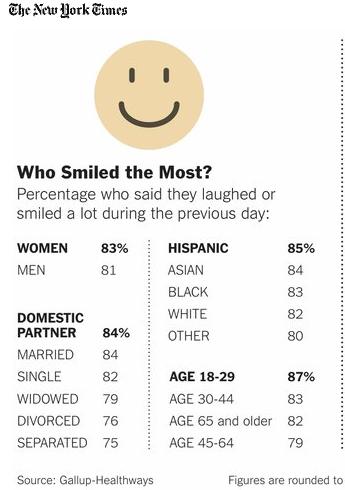

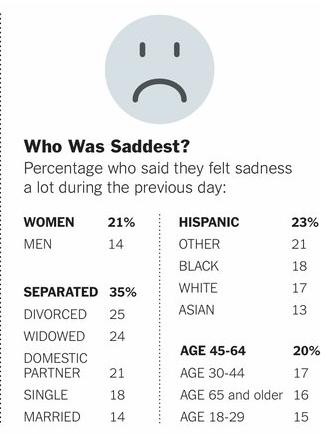

Finally, the NYT provides some demographic information on who was most likely to have said they spent a lot of the previous day laughing or smiling vs. being sad: