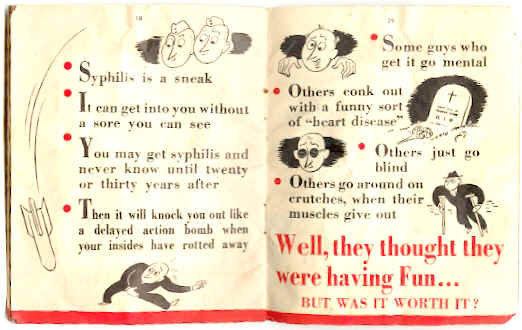

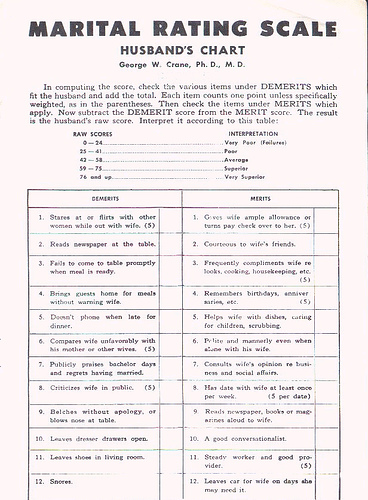

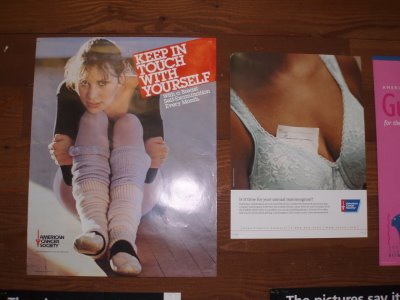

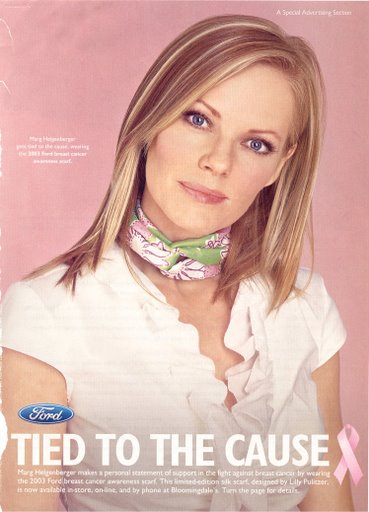

Myra M. F. sent us these four breast cancer awareness ads to compare and contrast (find them here). They are all super pink-ified (because men don’t get breast cancer… oh wait, they do), but the first two use stereotypical femininity and the latter two challenge them.

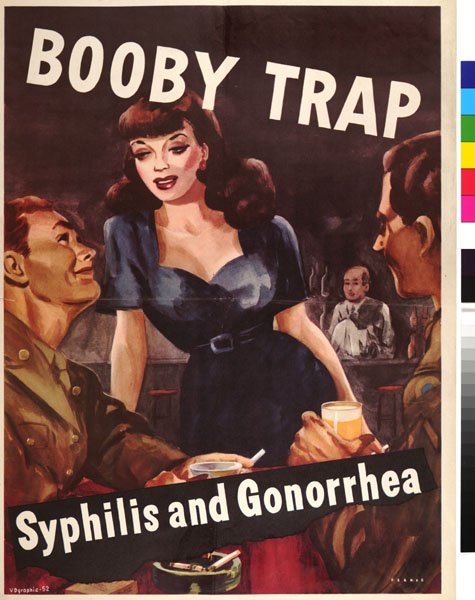

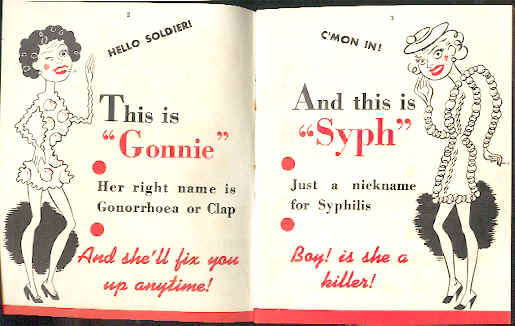

(1) Ah the lovely young middle-aged woman (I stand corrected), the ruffley white blouse, the slight head tilt, and the fashionable breast cancer scarf. You too can look oh so good while you fight breast cancer! Go Ford!

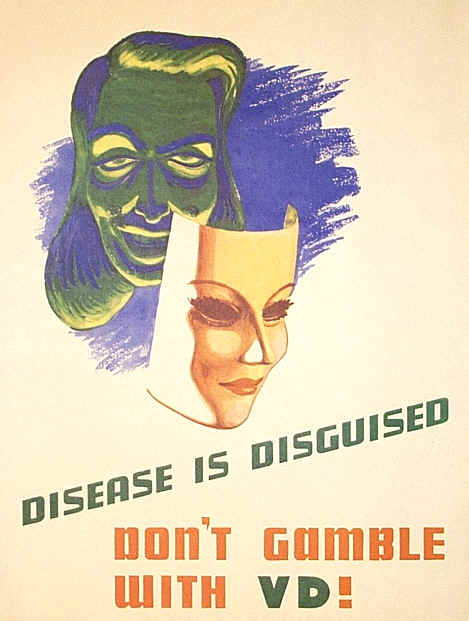

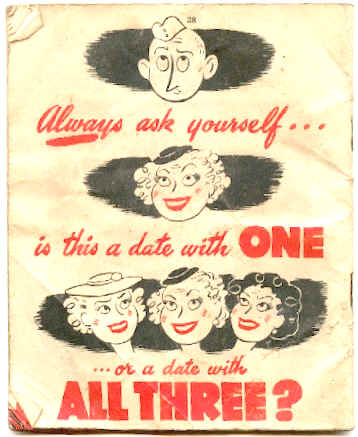

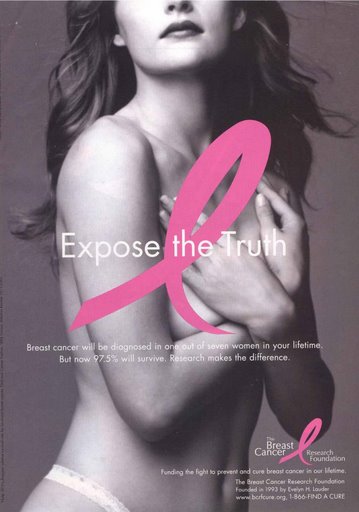

(2) “Expose the Truth.” Those awesome knockers on that gorgeous anonymous babe could someday be victims of breast cancer. And we can’t have that! Support breast cancer research!

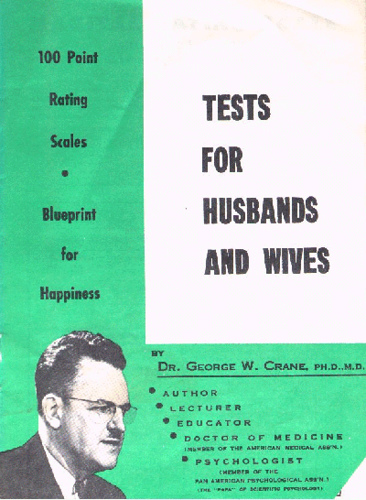

Consider how different these next two are:

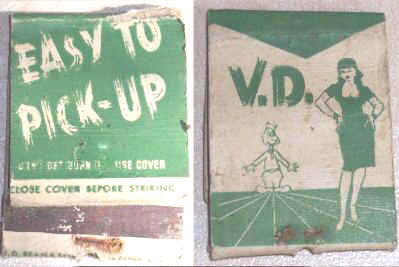

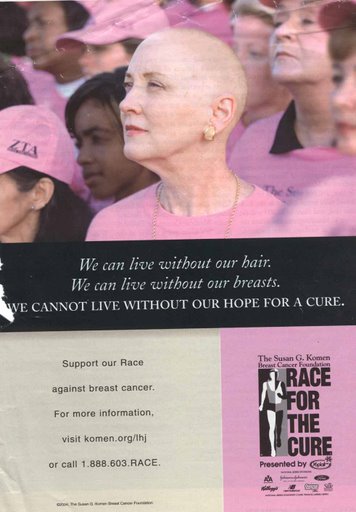

Here we see a woman who accepts some conventional definitions of femininity (make-up, pearls, earrings and, of course, pink), but rejects the idea that women should be ashamed to lose markers of femininity (“We can live without our hair. We can live without our breasts.”) and instead looks bravely towards a cure (“We cannot live without our hope for a cure.”) Plus, this image is about action (a race) instead of fashion (a scarf), suggesting that it is also a rejection of the idea that to be feminine is to be passive or powerless.

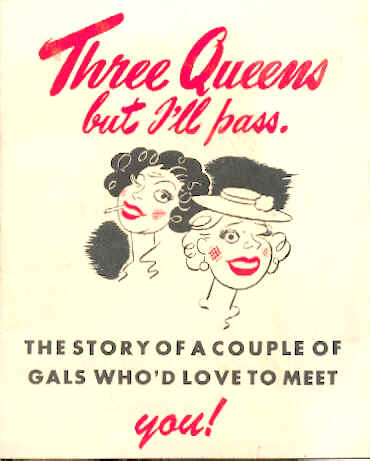

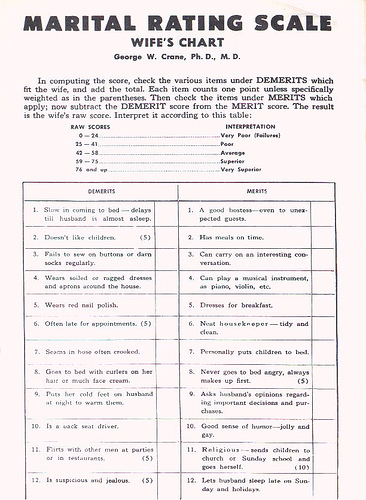

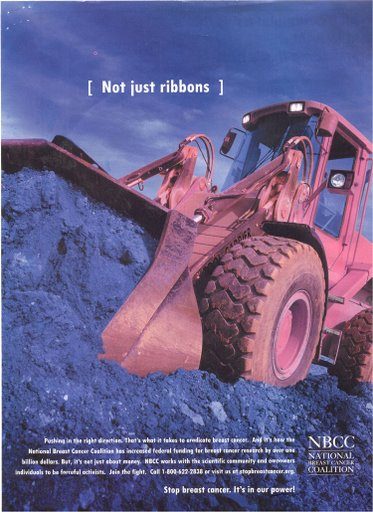

And this image actually mocks the symbolic ribbon and, I will add, bracelet activism (how feminine are ribbons and bracelets?), in favor of appropriating a masculine symbol (heavy machinery) by turning it pink and putting it to work against breast cancer. The text at the bottom says: “Stop breast cancer! It’s in our power!”

Four ads, all with the same message, all mobilizing femininity, but in two very different ways.

Thanks again to Myra!