We’re celebrating the end of the year with our most popular posts from 2013, plus a few of our favorites tossed in. Enjoy!

Oddly, three high profile female musicians find themselves in a public debate about what it means to be a feminist. We can thank Miley Cyrus for the occasion. After claiming that the video for Wrecking Ball was inspired by Sinead O’Connor’s Nothing Compares to You, O’Connor wrote an open letter to the performer. No doubt informed by Cyrus’ performance at the VMAs, she argued that the music industry would inevitably exploit Cyrus’ body and leave her a shell of a human being. Amanda Palmer, another strong-minded female musician, responded to O’Connor. She countered with the idea that all efforts to control women’s choices, no matter how benevolent, were anti-feminist.

I keep receiving requests to add my two cents. So, here goes: I think they’re both right, but only half right. And, when you put the two sides together, the conclusion isn’t as simple as either of them makes it out to be. Both letters are kind, compelling, and smart, but neither capture the deep contradictions that Cyrus – indeed all women in the U.S. – face every day.

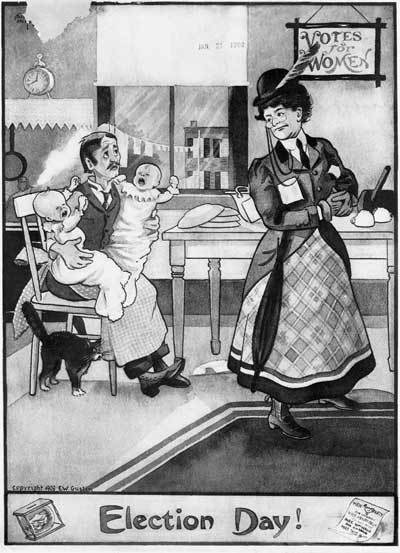

Cyrus in Wrecking Ball:

O’Connor warns Cyrus that the music industry is patriarchal and capitalist. In so many words, she explains that the capitalists will never pay Cyrus what she’s worth because doing so leaves nothing to skim off the top. The whole point is to exploit her. Meanwhile, her exploitation will be distinctly gendered because sexism is part of the very fabric of the industry. O’Connor writes:

The music business doesn’t give a shit about you, or any of us. They will prostitute you for all you are worth… and when you end up in rehab as a result of being prostituted, “they” will be sunning themselves on their yachts in Antigua, which they bought by selling your body…

Whether Cyrus ends up in rehab remains to be seen but O’Connor is, of course, right about the music industry. This is not something that requires argumentation, but is simply true in a patriarchal, capitalist society. For-profit industries are for profit. You may think that’s good or bad, but it is, by definition, about finding ways to extract money from goods and services and one does that by selling it for more than you paid for it. And media companies of all kinds are dominated at almost all levels by (rich, white) men. These are the facts.

Disagreeing, Palmer claims that O’Connor herself is contributing to an oppressive environment for women. All women’s choices, Palmer argues, should be considered fair game.

I want to live in a world where WE as women determine what we wear and look like and play the game as our fancy leads us, army pants one minute and killer gown the next, where WE decide whether or not we’re going to play games with the male gaze…

In Palmer’s utopia, no one gets to decide what’s best for women. The whole point is to have all options on the table, without censure, so women can pick and choose and change their mind as they so desire.

This is intuitively pleasing and seems to mesh pretty well with a decent definition of “freedom.” And women do have more choices – many, many more choices – than recent generations of women. They are now free to vote in elections, wear pants, smoke in public, have their own bank accounts, play sports, go into men’s occupations and, yes, be unabashedly sexual. Hell they can even run for President. And they get to still do all the feminine stuff too! Women have it pretty great right now and Palmer is right that we should defend these options.

So, both are making a feminist argument. What, then, is the source of the disagreement?

O’Connor and Palmer are using different levels of analysis. Palmer’s is straightforwardly individualistic: each individual woman should be able to choose what she wants to do. O’Connor’s is strongly institutional: we are all operating within a system – the music industry, in this case, or even “society” – and that system is powerfully deterministic.

The truth is that both are right and, because of that, neither sees the whole picture. On the one hand, women are making individual choices. They are not complete dupes of the system. They are architects of their own lives. On the other hand, those individual choices are being made within a system. The system sets up the pros and cons, the rewards and punishments, the paths to success and the pitfalls that lead to failure. No amount of wishing it were different will make it so. No individual choices change that reality.

So, Cyrus may indeed be “in charge of her own show,” as Palmer puts it. She may have chosen to be a “raging, naked, twerking sexpot” all of her own volition. But why? Because that’s what the system rewards. That’s not freedom, that’s a strategy.

In sociological terms, we call this a patriarchal bargain. Both men and women make them and they come in many different forms. Generally, however, they involve a choice to manipulate the system to one’s best advantage without challenging the system itself. This may maximize the benefits that accrue to any individual woman, but it harms women as a whole. Cyrus’ particular bargain – accepting the sexual objectification of women in exchange for money, fame, and power – is a common one. Serena Williams, Tila Tequila, Kim Kardashian, and Lady Gaga do it too.

We are all Miley, though. We all make patriarchal bargains, large and small. Housewives do when they support husbands’ careers on the agreement that he share the dividends. Many high-achieving women do when they go into masculinized occupations to reap the benefits, but don’t challenge the idea that occupations associated with men are of greater value. None of us have the moral high ground here.

So, is Miley Cyrus a pawn of industry patriarchs? No. Can her choices be fairly described as good for women? No.

That’s how power works. It makes it so that essentially all choices can be absorbed into and mobilized on behalf of the system. Fighting the system on behalf of the disadvantaged – in this case, women – requires individual sacrifices that are extraordinarily costly. In Cyrus’ case, perhaps being replaced by another artist who is willing to capitulate to patriarchy with more gusto. Accepting the rules of the system translates into individual gain, but doesn’t exactly make the world a better place. In Cyrus’ case, her success is also an affirmation that a woman’s worth is strongly correlated with her willingness to commodify her sexuality.

Americans want their stories to have happy endings. I’m sorry I don’t have a more optimistic read. If the way out of this conundrum were easy, we’d have fixed it already. But one thing’s for sure: it’s going to take collective sacrifice to bring about a world in which women’s humanity is so taken-for-granted that no individual woman’s choices can undermine it. To get there, we’re going to need to acknowledge the power of the system, recognize each other as conscious actors, and have empathy for the difficult choices we all make as we try to navigate a difficult world.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.