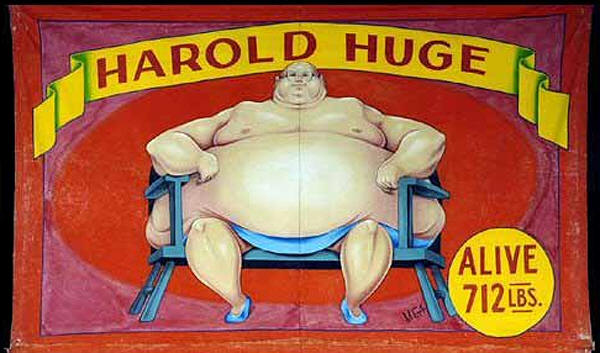

The Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM) sponsored two new billboards in Albany, NY, warning residents that cheese makes you fat in what is possibly most irresponsible way ever. The first features an obese man’s disembodied torso and the words, “Your abs on cheese.” The second features an obese woman’s butt and thighs and the words, “Your thighs on cheese.” The images make a very clear statement: fat people are disgusting.

The PCRM advocates for a vegan diet. The aim of this campaign is to get Albany residents to reduce their cheese intake, as cheese is a common source of saturated fat and, according to the PRCM, a major contributor to obesity in the United States. In Albany, home to several dairy farms, 63 percent of adults are obese. This is higher than the statewide obesity level of 59 percent. Obesity prevention is a valid cause, to be sure, but at what cost to other health issues?

The PCRM advocates for a vegan diet. The aim of this campaign is to get Albany residents to reduce their cheese intake, as cheese is a common source of saturated fat and, according to the PRCM, a major contributor to obesity in the United States. In Albany, home to several dairy farms, 63 percent of adults are obese. This is higher than the statewide obesity level of 59 percent. Obesity prevention is a valid cause, to be sure, but at what cost to other health issues?

According to their website, the PCRM is “a nonprofit health organization that promotes preventive medicine, conducts clinical research, and encourages higher standards for ethics and effectiveness in research.” For an organization so concerned with ethical standards, the PCRM has sunk pretty low with this offensive and damaging campaign. In the jargon of health communication ethics, the PCRM have committed a common and classic misstep: the failure to consider the unintended consequences of their message.

Just like a single food item (in this case, cheese) is not responsible for the entire obesity epidemic, obesity is not the only serious health problem facing Americans. We are also struggling with our body image and self-esteem as we cope with the barrage of photoshopped and unrealistic “ideal bodies” in the media. The National Eating Disorders Association states that “in the United States, as many as 10 million women and 1 million men are fighting a life and death battle with an eating disorder such as anorexia or bulimia. Millions more are struggling with binge eating disorder.”

In the medical hegemony, physical health tends to outrank mental health in “importance.” But the line between physical and mental health issues is not always clear, especially with the confluence of obesity, body image disturbance, eating disorders, and self-esteem. The PRCM is wearing blinders to these interrelated health issues in their dogmatic pursuit of a singular, isolated objective.

Physicians are taught to “do no harm.” The PRCM needs to understand that insensitive words and pictures are absolutely harmful to our health. There are better ways to educate and motivate people to make healthier food choices; ethical health campaigns do not sacrifice one health issue to promote another.

————————

Leah Berkenwald is a graduate student of Health Communication at Emerson College, in collaboration with the Tufts University School of Medicine, and holds a MA in American Studies from the University of Nottingham. She is currently designing a social marketing campaign on body image for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She also works as the Online Communications Specialist at the Jewish Women’s Archive, and blogs at talkinreckless.com.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.