(Found here, via Thick Culture.)

(Found here, via Thick Culture.)

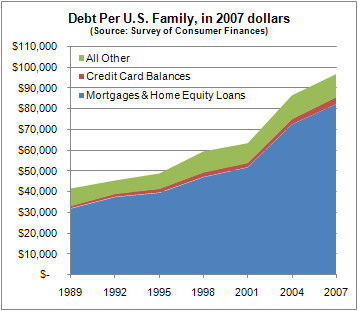

Nate Silver at FiveThirtyEight put up this graph of U.S. household debt (from the 2007 Survey of Consumer Finances):

Silver says,

Per-family household debt increased by about 130% in real dollars between 1989 and 2007, from roughly $42,000 per family in 1989 to $97,000 eighteen years later. Most of that increase has come during the past six or seven years — household debt increased by 52% between 2001 and 2007 alone. Almost all of the debt (about 85%) falls into the category that the Fed calls “secured by residential property” — which means mortgages and home-equity loans.

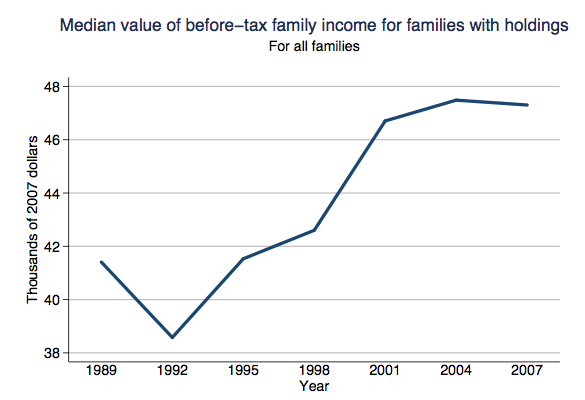

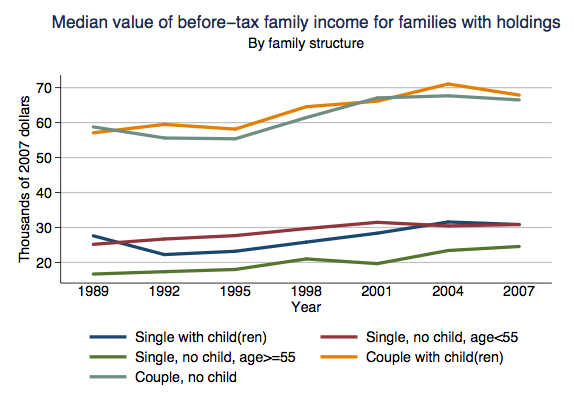

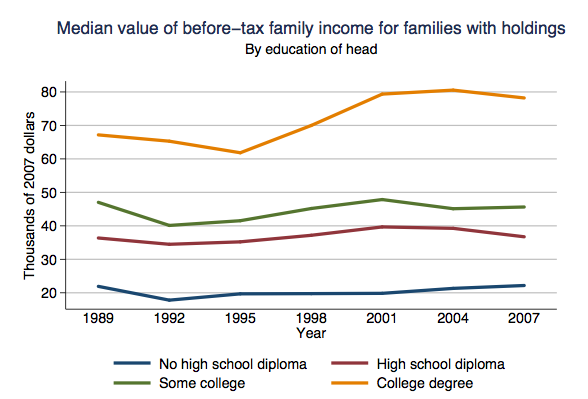

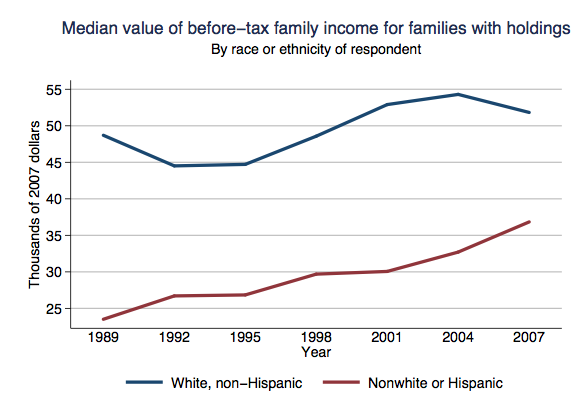

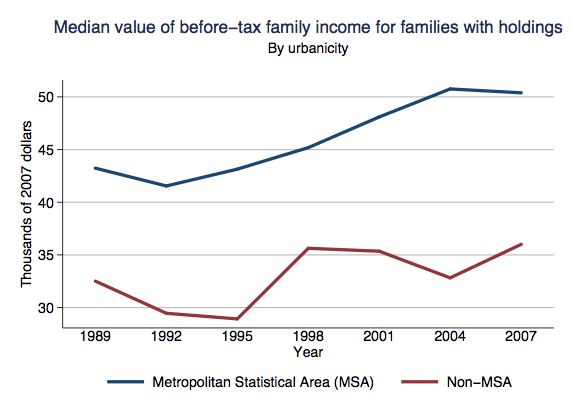

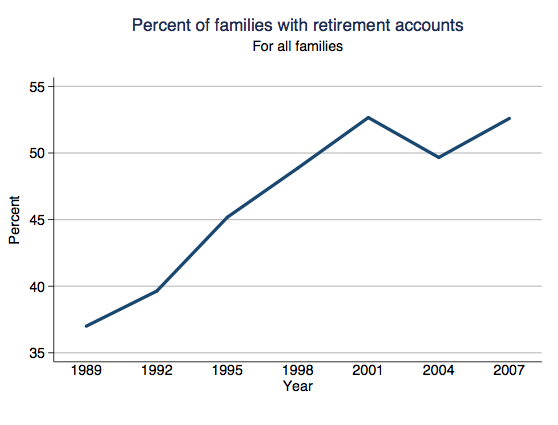

Some other images from the SCF Chartbook (available here)–and pay attention to the y axis, since the scale isn’t the same in all of them:

This next one is for rural (non-MSA) and urban (MSA) areas:

The Chartbook has images of the mean values for all these calculations as well, I just prefer the median to reduce the effects of outlier incomes.

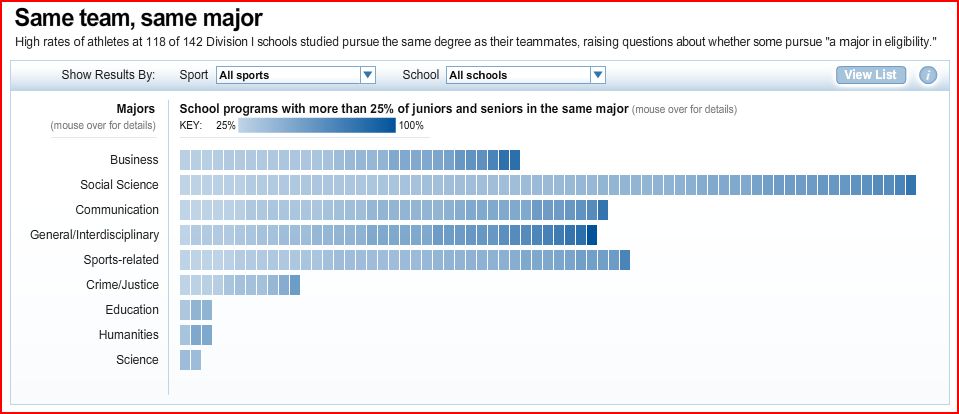

USA Today posted an interactive graphic demonstrating how different types of college athletes cluster into majors differently at different schools (via Montclair Socioblog). For example, the screenshot below includes the data for all athletes in the study. Each rectangle represents a school; the darker the blue, the more concentrated major choices are for that team at that school. In this iteration, the darkest blue rectangle in the “social science” category represents Louisiana Tech at which 80 percent of male basketball players major in Sociology:

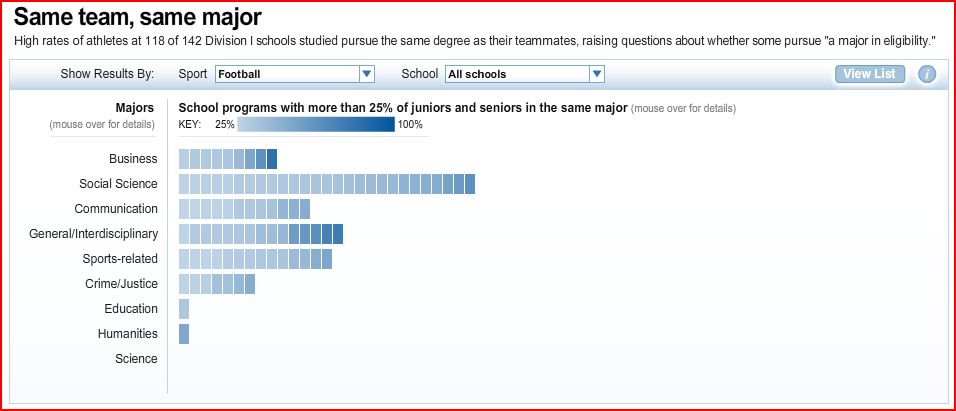

This screenshot features football players only. At Georgia Tech, 82 percent of football players major in Business:

If you visit the site, you can manipulate the graphic as you like and see what school and team each rectangle represents.

Certain majors have long been rumored to be athlete friendly and I think this actual data sheds a lot of light on the false stereotype of both disciplines and athletes.

The article doesn’t speculate as to why teammates cluster, but we could…

I was recently speaking to a colleague at my College who remembered a time during which a good percentage of the football players majored in Sociology. He suggested that this was because one of the most high-profile football players, one who was very well-liked by his teammates and had a leadership role on the team, majored in Sociology. Since that player has left the College, the percent of football players in our major has decreased. In that sense, part of the explanation for why teammates cluster may be more social psychological than sociological.

What are your theories?

As former a sexual health educator and current sexuality studies professor, I meet students whose ideas about sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) have been shaped by the ‘scary slideshow’: that series of full-color, close-up shots of the worst infections.

(Not safe for work–explicit images of STDs)

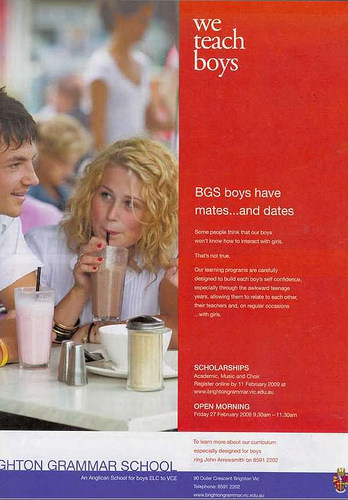

Lauredhel of Hoyden about Town sent in this ad for Brighton Grammar School, an Anglican boys’ school in Australia:

Text:

BGS boys have mates…and dates. Some people think that our boys won’t know how to interact with girls. That’s not true. Our learning programs are carefully desgined to build each boys self confidence, especially through the awkward teenage years, allowing them to relate to each other, their teachers, and, on regular occasions…with girls.

Huh. I like how they’re using the promise of access to girls to market the school. And indeed, it appears that they do teach boys things, including to expect cute girls to gaze at them adoringly.

I don’t know much about the assumptions surrounding all-boys or all-girls schools. Is there a belief that kids who go to them won’t be able to interact with the other sex? Or is this about fears parents have about homosexuality at all-boys schools? Is the school letting them know they don’t have to worry because their sons will have tons of opportunities to hang out with pretty girls?

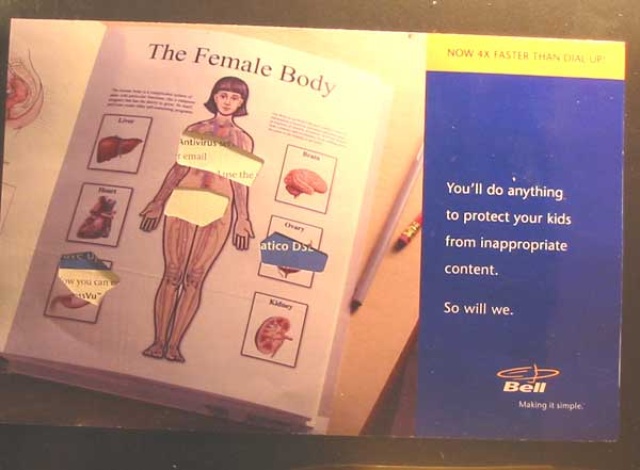

Julie C. drew our attention to this ad for an internet service that filters “inappropriate” content:

Lizvang nicely articulates an objection (my emphasis):

The breasts, the vagina, the uterus and the colon is cut out of an anatomical text book. When did biology and education about our bodies become shameful? Haven’t we as a society moved past the “a woman’s body is dirty” mindset?

Francisco (from GenderKid) sent in a cartoon that questions the benefits of the One Laptop per Child program, which aims to give a simple version of a laptop with internet access to kids in less-developed nations, and also Alabama (available at World’s Fair):

From the OLPC program’s website:

Most of the more than one billion children in the emerging world don’t have access to adequate education. The XO laptop is our answer to this crisis—and after nearly two years, we know it’s working. Almost everywhere the XO goes, school attendance increases dramatically as the children begin to open their minds and explore their own potential. One by one, a new generation is emerging with the power to change the world.

There are a number of interesting elements you might bring up here, such whether introducing laptops is necessarily the best method to improve education wordwide, or who decided that this was an important need of children in these regions (my guess is the MIT team behind OLPC didn’t go to communities and do surveys asking what local citizens would most like to see for their educational system). I recently heard a story about OLPC on NPR, and while there seemed to be benefits in some Peruvian communities, in others the teachers spent so much time trying to figure out how to use the machines to teach subjects, without really feeling comfortable with them, that almost nothing was accomplished during the day. But once the laptops were introduced, they overtook the classroom; teachers were pressured by the Peruvian government to use the laptops in almost every lesson, even if it slowed them down or it wasn’t clear that students were benefiting from them. Another problem was that, though the laptops are built to be very strong and difficult to break, on occasion of course one will break. Families must pay to repair or replace them, which of course most can’t do, meaning kids with broken laptops had to sit and watch while other kids used theirs in class.

Benjamin Cohen uses the OLPC in an engineering class and brings up concerns about…

technological determinism — [the idea] that a given technology will lead to the same outcome, no matter where it is introduced, how it is introduced, or when. The outcomes, on this impoverished view of the relationship between technology and society, are predetermined by the physical technology. (This view also assumes that what one means by “technology” is only the physical hunk of material sitting there, as opposed to including its constitutive organizational, values, and knowledge elements.) In the case of OLPC, the project assumes equal global cultural values & regional attributes. It also assumes common introduction, maintenance, educational (as in learning styles and habits), and image values everywhere in the world. Furthermore, it lives in a historical vacuum assuming that there is no history in the so-called “developing world” for shiny, fancy things from the West dropped in, The-Gods-Must-Be-Crazy style, from the sky.

How could the same laptop have the same meaning and value in, say, Nigeria and Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Alabama, Malawi and Mongolia?

These critiques aren’t to say there is no value in OLPC, but that there are some clear questions about whether this is the most effective way to improve education in impoverished or isolated communities and what its consequences are. I doubt the OLPC creators meant for teachers to face government pressure to use the laptops for every lesson, no matter what, but that’s what has happened in at least some areas.

Another problem the NPR story highlighted was that the kids they reported about in Peru live in areas where there are absolutely no jobs available to capitalize on their tech skills, nor any reason to believe there will be any time soon. The government is pushing laptops in education, but without any economic development program to bring jobs to the regions to take advantage of these educated students. So the question is, after you get your laptop, you learn how to use it, you graduate…then what? Will the laptops spur more brain drain and out-migration? Is this necessarily good? Are countries like Peru using the laptop program as a quick, flashy substitute for the more boring, difficult, challenging process of economic development and job creation? As an educator, I’m thrilled with the idea of valuing learning and knowledge for its own sake, but on a more practical level, these questions seem like important ones.

Thanks, Francisco!

UPDATE: In a comment, Sid says,

…there’s kind of a vaguely imperialistic nostalgia in the first image of “Darkest Africa” as a simpler, more wholesome place where kids still play together in front of the hut and there’s a sense of community that you just don’t get in the modern world and blahdee blahdee blah. The entire thing kind of smacks of a whitemansburden.org enterprise…

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.