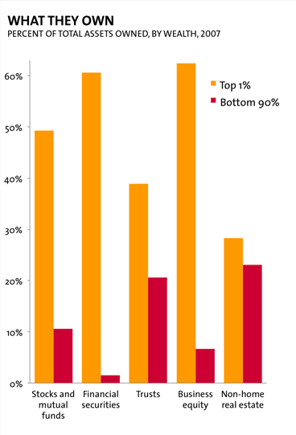

I can’t teach my course on family sociology without these graphs, which show the rise of the unfree population, and the incredible race/ethnic and gender disparities behind them.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics has released Correctional Population in the United States, 2010, which updates my standard figures. First, the total trend toward unfreedom in the population — from less than 2 million in 1980 to more than 7 million 30 years later:

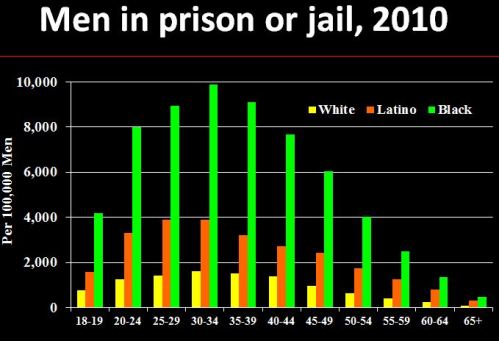

And second, to understand the disparate impact of this change on Black men in young adulthood primarily — and secondarily, Latino men — here are the rates of incarceration for men by age and race/ethnicity (Blacks here exclude Latinos; Asians and American Indians are not included in the statistics):

Just to make sure you read the scale right, that incarceration rate for Black men in their early 30s is 9,892 per 100,000, or 9.9%, or one-in-ten — more than five-times the rate for White men.

I come at this largely from its effects on families. In a nutshell: The overall trend is largely a consequence of how the U.S. has waged its drug war over this period; these policies fit into a web of practices that deny families to millions of people in the U.S. (only a minority of whom have been convicted of crimes), including by simply removing men from communities and increasing the number of single-parent families.

All that said, you may notice the little decline at the end of that long upward trend in the first figure. In fact, for the first time since 1980, there has been a decline in the incarcerated population for two years running. There has been a long-term decline in crime, but I don’t know whether that is more important than the budget crises facing so many states, or the diminished lust for locking people up. In New York, for example, seven incarceration facilities were closed in the last year, after the number of prisoners dropped about one-fifth in the past decade:

The inmate decline followed a 25 percent statewide drop in crime over the past decade and revisions in sentencing laws that allowed earlier releases and alternative programs for nonviolent drug offenders. The number of prisoners in medium-security prisons declined almost 20 percent from 2001 to 2010 while those in minimum-security facilities dropped 57 percent.

The numbers on the charts are still off the charts, meanwhile — and remember these are just those in the system now. Many more people (and their families) live lives permanently hampered by criminal records and the experience of imprisonment.