I wrote this for The Conversation. Read the original here.

Observers may be quick to declare social trends “good” or “bad” for families, but such conclusions are rarely justified. What’s good for one family – or group of families – may be bad for another. And within families, interests do not always align. Divorce is “bad” for a family in the sense of breaking it apart, but it may be beneficial, or even essential, for one or both partners or their children.

This kind of ambiguity makes it difficult to assess what kind of impact the recent recession and its aftermath had on families. But for researchers, at least, it offers a lot of job security – so many questions, so much going on. In any case, here’s where we stand so far.

The effect of the Great Recession on family trends in the United States has been dramatic with regard to birth rates and divorce, and has been strongly suggestive of family violence, but less clear for marriage and cohabitation.

Marriage rates declined, and cohabitation rates increased, but these trends were already underway, and the recession didn’t alter them much. When trends don’t change direction it’s difficult to identify an effect of a shock this broad. However, with both birth rates and divorce, clear patterns emerged.

Birth rates: a sharp drop

The most dramatic impact was on birth rates, which dropped precipitously, especially for young women, as a result of the economic crisis. How do we know? First, the timing of the fertility decline is very suggestive. After increasing steadily from the beginning of 2002 until late 2007, birth rates dropped sharply. (The decline has since slowed for some groups after 2010, but the U.S. still saw record-low birth rates for teenagers and women ages 20-24 as late as 2012.)

Second, the decline in fertility was steeper in states with greater increases in unemployment. Although we don’t have the data to determine which couple did or did not have a child in response to economic changes, this pattern supports the idea that financial concerns convinced some people to not have a child.

That interpretation is supported by the third trend: the fertility drop was more pronounced among younger women – and there was no drop at all among women over 40. That may mean the fertility decline represents births postponed by families that intend to have children later – an option older women may not have – which fits previous research on economic shocks.

It seems likely that people who are on the fence about having a baby can be swayed by perceived financial hardship or uncertainty. From research on 27 European countries, we know that people with troubled family financial situations are more likely to say they are unsure whether they will meet their stated childbearing goals – that is, economic uncertainty doesn’t change their familial aims but may increase uncertainty in whether they will be met.

However, some births delayed inevitably become births foregone. Based on the effect of unemployment on birth rates in earlier periods, it appears a substantial number of young women who postponed births will end up never having children. By one estimate, women who were in their early 20s during the Great Recession are projected to have some 400,000 fewer lifetime births and an additional 1.5% of them will never have a birth.

Divorce rates: a counter-intuitive reaction

In the case of divorce, the pattern is counter-intuitive. Although economic hardship and insecurity adds stress to relationships and increases the risk of divorce, the overall divorce rate usually drops when unemployment rates rise.

Researchers believe that, like births, people postpone divorces during economic crises because of the costs of divorcing – not just legal fees, but also housing transitions (which were especially difficult in the Great Recession) and employment disruptions.

My own research found that there was a sharp drop in the divorce rate in 2009 that can reasonably be attributed to the recession. But, as we suspect will be the case with births, there appears to have been a divorce-rate rebound in the years that followed.

Domestic violence: a spike along with joblessness

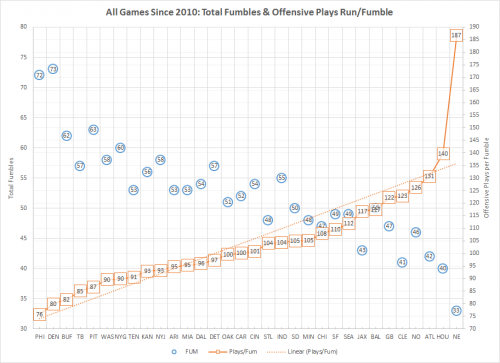

Family violence has become much less common since the 1990s. The reasons are not entirely clear, but they certainly include the overall drop in violent crime, improved response from social service and non-governmental organizations, and improvements in women’s relative economic status. However, when the recession hit there was a spike in intimate-partner violence, coinciding with the sharp rise in men’s unemployment rates (I show the trends here).

As with the other trends, it’s hard to make a case based on timing alone, but the evidence is fairly strong that the economic shock increased family stress and violence. For example, one study showed that mothers were more likely to report spanking their children in the months when consumer confidence fell. Another study found a jump in abusive head trauma cases during the recession in several regions. And there have been many anecdotal and journalist accounts of increases in family violence, emerging as early as 2009. Are these direct results of the economic stress or mere correlation? It’s hard to say for sure.

The ultimate impact of these trends on American families will likely take years to emerge. The recession may have affected the pattern of marriage in ways we don’t yet understand – how couples selected each other, who got married and who didn’t – and may create measurable group of marriages that are marked for future effects as yet unforeseen. Like the young adults who entered the labor market during the period of high unemployment and whose career trajectories will be forever altered unfavorably, how these families bear the scars cannot be predicted. Time will tell.

Philip N. Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland, College Park. He writes the blog Family Inequality and is the author of The Family: Diversity, Inequality, and Social Change. You can follow him on Twitter or Facebook.