In the 1800s, the Irish (whether in Ireland, Britain, or the U.S.) were often very negatively stereotyped. In many cases the same negative characteristics attributed to Africans and African Americans (sloth, immorality, destructiveness) were often also associated with the Irish. In fact, some scientists believed the Irish were, like Africans, more closely related to apes than to other Europeans, and in some cases in the U.S., Irish immigrants were classified as Blacks, not Whites.

The next three political cartoons from the 1800s were found on the Nevada Department of Education website section about racism (as was the quote about the first cartoon).

This one is titled “The Workingman’s Burden” and depicts “a gleeful Irish peasant carrying his Famine relief money while riding on the back of an exhausted English laborer.” It might make a good comparison to how welfare recipients are viewed in the U.S.

This illustration ran in Harper’s Weekly magazine. Notice how the Irish are depicted as more similar to “Negros” than to “Anglo Teutonic” individuals, and both the Irish and Africans are caricatured as ape-like. It could also be useful for a discussion of scientific racism.

This cartoon, titled “Two Forces,” shows a figure representing Britain protecting a weeping, frightened woman, representing Ireland, from a rampaging Irishman; notice his hat says “anarchy.”

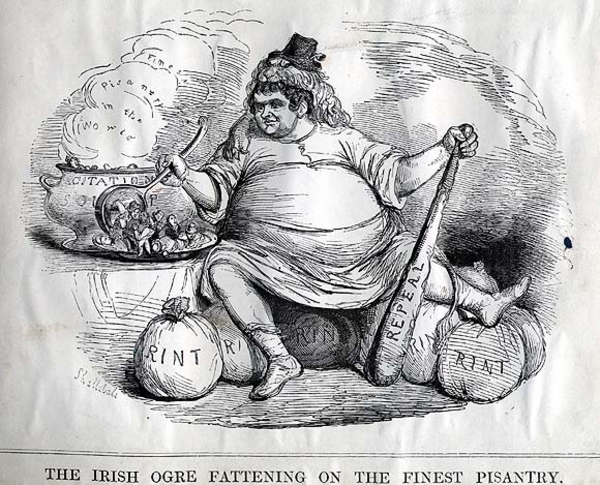

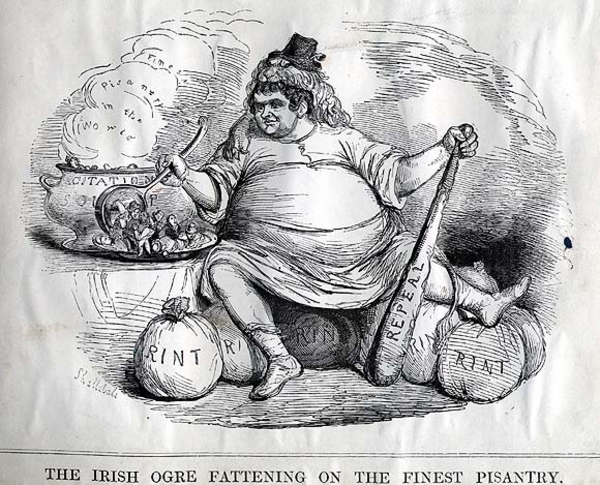

This image, found at the University College Cork website, depicts Daniel O’Connell, a leader of the Irish land reform movement, as an “ogre.” He is ladling poor Irish peasants out of a pot labeled “agitation soup,” and, presumably, cheating them out of money in the guise of helping them.

Here we see the Irish depicted as a Frankensteinian monster in a cartoon that ran in Punch in 1882 (image found at the website for a course at the University of St. Andrews):

These next three all come from the Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. Here we see drunken Irishmen rioting and attacking police:

In this one, John Bull (representing Britain) and Uncle Sam look on as an Irish man engages in reckless destruction; notice the empty bottle in the lower right corner, labeled “drugs”:

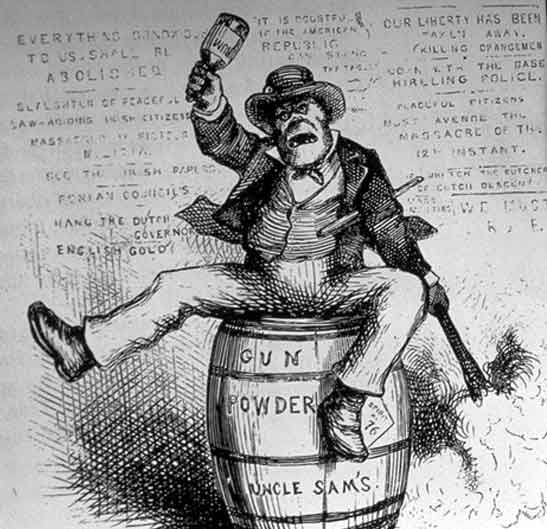

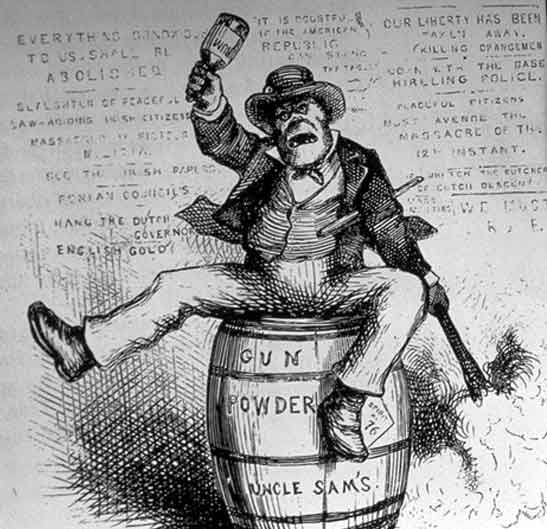

Here an ape-like Irish man, again drunk, sits on a powder keg, presumably threatening the entire country:

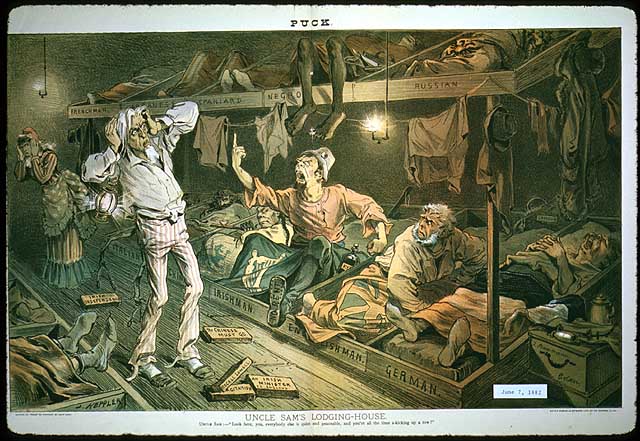

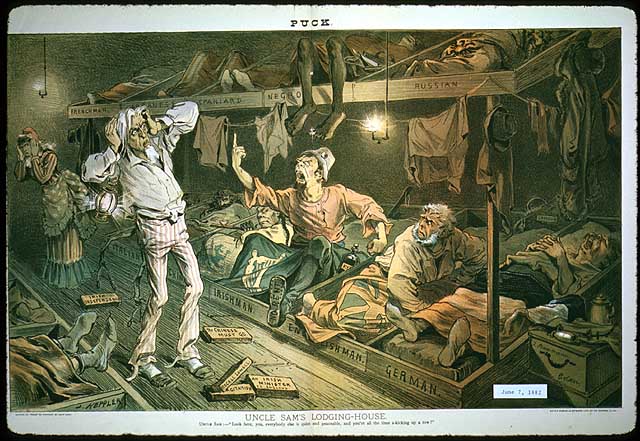

Finally, this one, published in 1882 (and found at the Michigan State University Museum website), is called “Uncle Sam’s Lodging House” and shows an Irish immigrant causing a commotion while other immigrants (notice the beds are labeled Russian, German, Negro, etc.) try to sleep. The smaller caption under the title says, “Look here, you, everybody else is quiet and peaceable, and you’re all the time a-kicking up a row!”

The message is, of course, that other immigrant groups (including Blacks) settle in and don’t cause problems, while the Irish don’t know how to assimilate or stay in their place.

You might compare these images to this recent post about how symbols of Irishness have lost any real negative implications, such that even politicians in non-Irish-dominated districts feel comfortable using them in campaign materials.

And yes, I know I’ve been posting a lot of stuff about race and ethnicity lately. I’m teaching a class on it this semester–it’s the stuff that I keep coming across while writing lectures.

And I’m dedicating this post to my boyfriend, Burk, who decided to go on a date with me even though, when he asked if I’d have trouble dealing with his hard-drinking Irish-American family, I said I could handle that but wouldn’t put up with any blubbering on about how Angela’s Ashes is the best book ever.

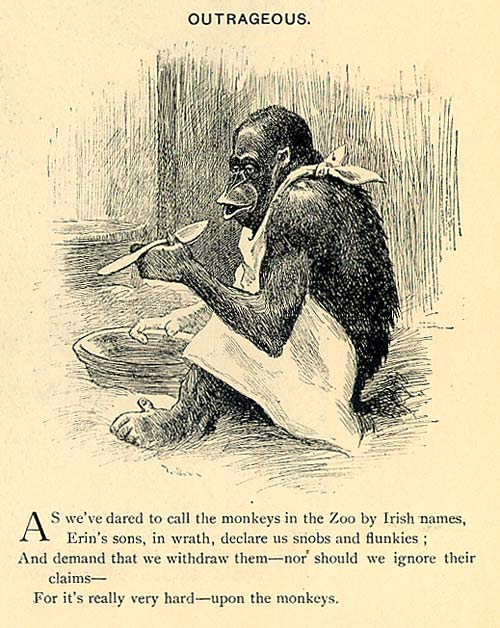

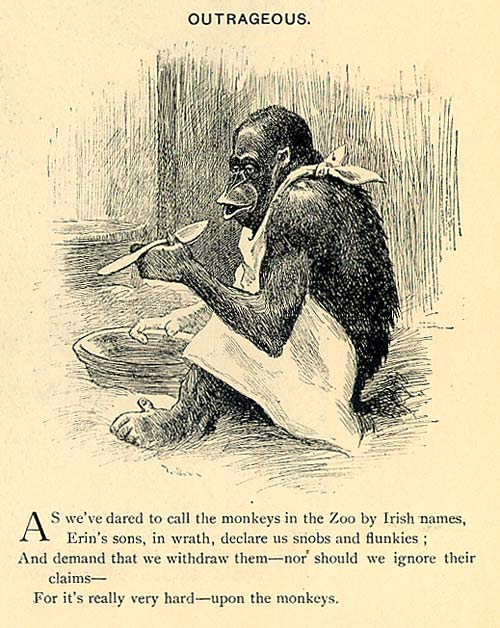

NEW! This cartoon with poem was published in Life Magazine on May 11th, 1893. The poem is suggesting that the monkeys in the zoo are sad that they get called by Irish names.

Text:

As we’ve dared to call the monkeys in the Zoo by Irish names, Erin’s sons, in wrath, declare us snobs and flunkies ;

And demand that we withdraw them–nor should we ignore their claims–

For it’s really very hard–upon the monkeys.

UPDATE: In a comment, Macon D asked how I address the ways in which Whites of some ancestries (Irish, Italian, etc.) often point to the fact that there was discrimination against those groups as a way of invalidating arguments about systemic racism. The logic is that both non-Whites and some White groups faced prejudice and discrimination but European groups overcame it through their own hard work, and thus any other group could too. If they continue to experience high levels of poverty, unemployment, or any other social problem, it is due to their own lack of hard work, intelligence, or some other characteristic.

I do indeed discuss this argument at length whenever I teach about race. A great reading to address it is Charles Gallagher’s article “Playing the White Ethnic Card: Using Ethnic Identity to Deny Contemporary Racism,” p. 145-158 in White Out: The Continuing Significance of Racism (2003, Ashley W. Doane and Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, editors, New York: Routledge). The tone might put some students off, because it doesn’t baby them or try to sugar-coat the issue of how Whites use their (often imagined) family stories of discrimination as a way to argue that systemic racism doesn’t exist and that they got to where they are by their family’s hard work, and nothing more. I know other professors often use the “How Jews Became White Folks” reading by Karen Brodkin, which also looks at this issue.

I also spend a good part of the semester looking at how government policies have had the effect of transferring enormous amounts of wealth into the hands of European immigrants and helping them accumulate resources over time–we look at the Homestead Act of 1862, the G.I. Bill (which Black veterans were often excluded from using), and how government subsidies for building suburban subdivisions were actively denied to groups wanting to build integrated communities. All these are examples of ways in which White Americans were aided in acquiring wealth and moving up the socio-economic ladder, while non-Whites often were explicitly excluded from these benefits.

I also point out that, while in these images the Irish are negatively stereotyped, it is clear that they are still viewed less negatively than, say, Africans or African Americans. If the Irish are the “missing link” between Africans and Caucasians…that still means they’re considered more evolved than Africans–at least somewhat more fully human. So even at the height of discrimination against White European groups, that did not necessarily mean they were treated “the same” as, say, American Indians or Blacks.