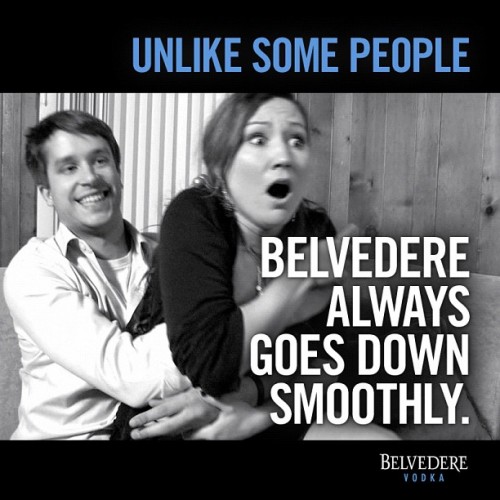

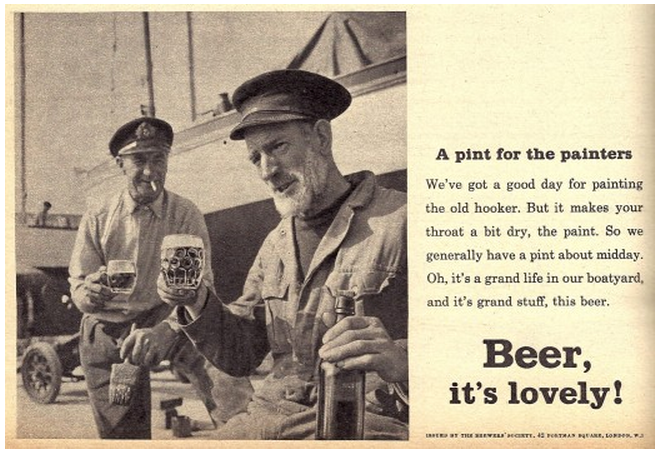

YetAnotherGirl, Andrew, Rosemary, Nathan Jurgens0n, Dolores, and Ann K. all sent in an ad for Belvedere Vodka that should be listed in the annals of bad ideas. The ad shows a gleeful man grabbing a distressed-looking woman who, we are to presume from the text, must not be going down smoothly (via Feministing):

Because how is it not funny to present your product in a context that says sexual assault is funny?

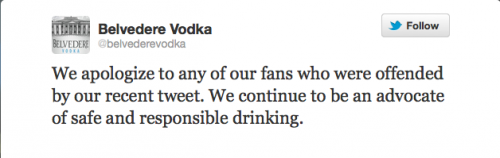

Online criticism of an ad that seems to be making a joke about forcing women to engage in sexual acts led to the company pulling the ad and issuing an apology of the passive “sorry if you were offended” type:

The company’s president also apologized when speaking to CNN about the controversy (via The Consumerist):

It should never have happened. I am currently investigating the matter to determine how this happened and to be sure it never does so again. The content is contrary to our values and we deeply regret this lapse.

The company also made a donation to the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network (RAINN).

Phil Villarreal, who posted about the ad and the apology at The Consumerist, suggests that the ad may be even more cynical than it at first appears:

The cynical might wonder whether or not the campaign and apology made up a coordinated effort to draw attention to the brand.

Intentionally invoking outrage, then making an apology and symbolic corporate donation as marketing strategy. Any readers with marketing expertise have any insight here? We often see cases of companies desperately trying to control the negative effects of controversies. When does a controversy hurt a brand and when does it serve as a marketing opportunity?

UPDATE: Reader Tom points out that it turns out to be a still from a parody video that someone at the company then reposted (via Adland):

Somebody on their social media team obviously created (or found) and posted it thinking it was an amusing parody. And that person has probably been found and fired.

But it is unlikely anyone officially *in charge* of the brand actually saw and approved this.

As Tom says, this brings up a separate issue: the challenges to companies of managing brand image in a world where one person in the organization can quickly disseminate something via the company’s social networking sites to thousands or even millions of people with much less oversight than a traditional ad campaign would get, especially when viewers make little distinction between images included in tweets or Facebook updates and those in billboards, print ads, etc.