Cross-posted at Ms. and Caroline Heldman’s Blog.

The Hunger Games should serve as a wake-up call to Hollywood that women action-hero movies can be successful if the protagonist is portrayed as a complex subject — instead of a hyper-sexualized fighting fuck toy (FFT).

The Hunger Games should serve as a wake-up call to Hollywood that women action-hero movies can be successful if the protagonist is portrayed as a complex subject — instead of a hyper-sexualized fighting fuck toy (FFT).

In its first weekend, The Hunger Games grossed $155 million, making it the third highest opener of all time (behind the last Harry Potter film and The Dark Knight), despite a marketing budget half the size of a typical big-studio, big-budget film. It seized the records for top opener released outside of July, top non-sequel opener and top opener with a woman protagonist. By the second weekend, The Hunger Games had made $251 million in the U.S. — the fastest non-sequel to break the quarter-billion-dollar mark.

While the movie arguably plays up the romance angle more than the books, The Hunger Games is still squarely an action thriller, set in a dystopic future world where teens fight to the death in a reality show.

Its success is largely based on the wide appeal of its teenage hero, Katniss Everdeen, who makes it through the movie without being sexually objectified once — a rarity in action films. Katniss is a believable, reluctant hero.

Katniss succeeds with audiences where other women heroes have failed because she isn’t an FFT. Fighting fuck toys are hyper-sexualized women protagonists who are able to “kick ass” (and kill) with the best of them — and look good doing it. The FFT appears empowered, but her very existence serves the pleasure of the heterosexual male viewer. In short, the FFT takes female agency and appropriates it for the male gaze.

From an ethical standpoint, Hollywood executives should be concerned about the damage girls and women sustain growing up in a society with ubiquitous images of sex objects. But it appears they are not. From a business standpoint, then, they should be concerned about the money they could be making with better women action heroes. But so far, they seem pretty clueless.

Hollywood rolls out FFTs every few years that generally don’t perform well at the box office (think Elektra, Catwoman, Sucker Punch), leading executives to wrongly conclude that women action leads aren’t bankable. In fact, the problem isn’t their sex; the problem is their portrayal as sex objects. Objects aren’t convincing protagonists. Subjects act while objects are acted upon, so reducing a woman action hero to an object, even sporadically, diminishes her ability to believably carry a storyline. The FFT might have an enviable swagger and do cool stunts, but she’s ultimately a bit of a joke.

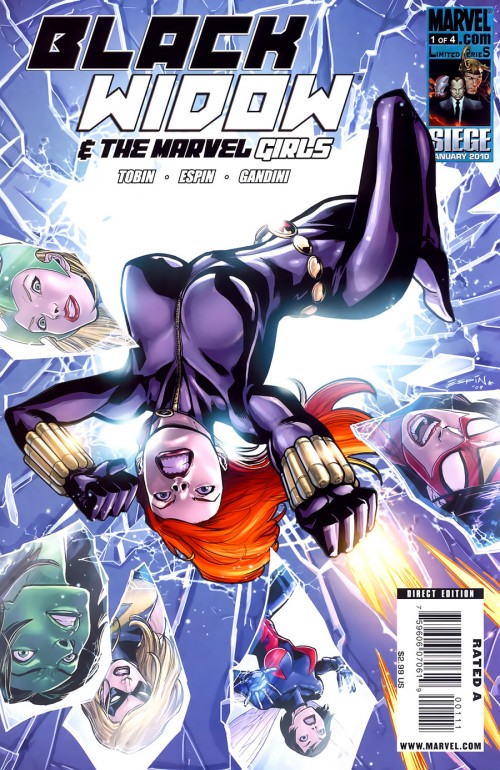

For a breakdown of why FFTS lack believability and appeal, check out the Escher Girls tumbler, a site that critiques the ridiculous physical contortions of FFTs that allow them to be both sex objects and action heroines. Contortions like this:

As Mark Hughes from Forbes.com points out, movie studios artificially limit their profits when they target only male audiences (by, for instance, by portraying women only as FFTs). With the phenomenal success of The Hunger Games, Hollywood can no longer deny the bankability of believable women action leads. Forty percent of the audience for The Hunger Games is male, proving that a kick-ass woman lead who isn’t reduced to a sex object can appeal to all genders. That should put dollar signs in executives’ eyes.

Hollywood is now on a quest to find the next Katniss Everdeen. Whoever she is, the question will be: Do executives know better than to turn her into a fighting fuck toy?