Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

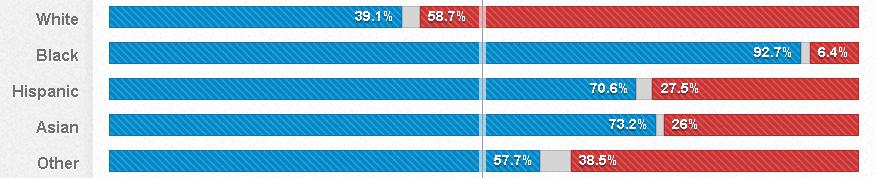

In a democracy, all votes are created equal — one person, one vote -– but apparently some votes are more equal than others. Obama won the electoral college vote 62% – 38%, though his margin in the popular vote was much smaller: 51% – 48%.

A similar discrepancy happened in the vote for Congressional representatives. The Republicans control the House of Representatives, where they have 54% of the seats. But if you add up all the votes for those seats, the Democrats come out slightly ahead (by about 500,000 votes). More votes but fewer seats.

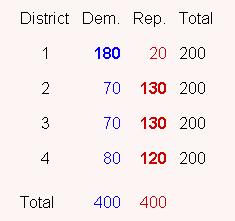

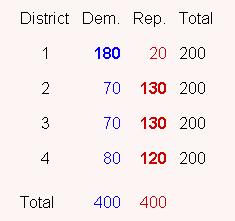

That discrepancy arises from the distribution of Democrats and Republicans in a state’s Congressional districts. Take a hypothetical state with four districts, each with 200 people. The popular vote splits evenly –- 400 Democrats, 400 Republicans. Here are the election results:

The Republicans have 50% of the popular vote but get 75% of the seats.

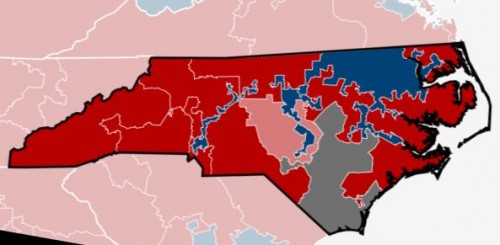

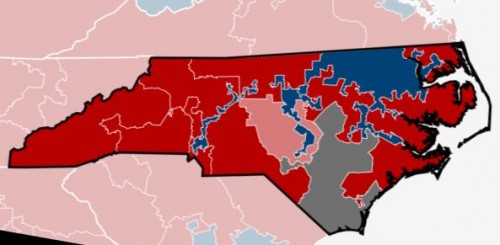

Less hypothetically, in North Carolina, Democratic candidates outpolled Republicans 2.22 million to 2.14 million. But Republicans won 10 of the 14 seats. The Democratic votes were crowded into four districts. In three of those four districts, the Democrats won big – by an average of 133,000 votes. (If the 7th district, where Democrats now have a slim lead, goes Republican, that average margin will be 177,000.) Had some of the Democrats from one of those districts been mapped into the neighboring district, they might have won both, though by smaller margins. The Republican districts had secure but smaller majorities. Republican winning margins averaged 50,000 votes, less than half the margin where Democrats won.

My first thought was that this was pure Gerrymandering. State legislatures get to draw the maps of their Congressional districts. And many more state legislatures are controlled by Republicans. In fact, some of the North Carolina districts have unusual shapes. The NC-12, the thin blue line along Interstate 85 stretching nearly to the border, was created as a “majority-minority” district so that Black votes would not be diluted. The downside for Democrats is that it packs those votes into that narrow corridor. So the Democrats take that district by over 180,000 votes. The Republicans with the neighboring districts but by much smaller margins – 23,000, 25,000, and 53,000. In those four districts, the Democrats got 53% of the vote, but Republicans took three of the four seats.

The Democratic district snaking down through the middle of the state is the 4th, which contains “the Triangle” to the north, but now has that tail stretching down. Democrats carried the district by 170,000 votes. Surrounding it is the 2nd (in pink), which Republicans carried by only 45,000 votes.

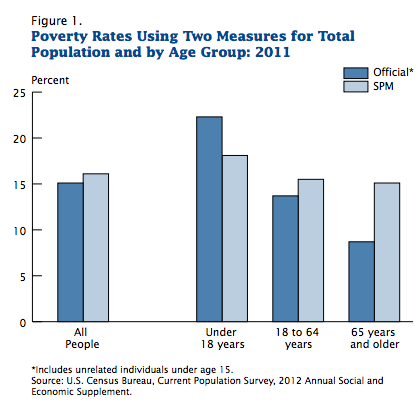

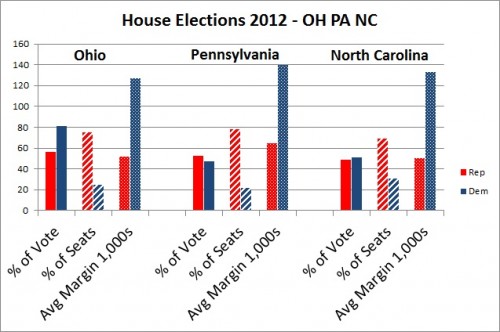

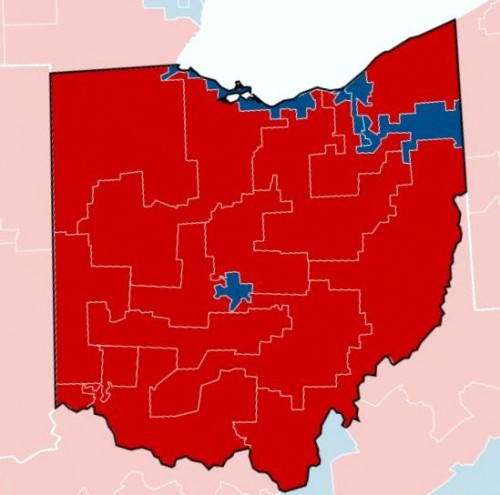

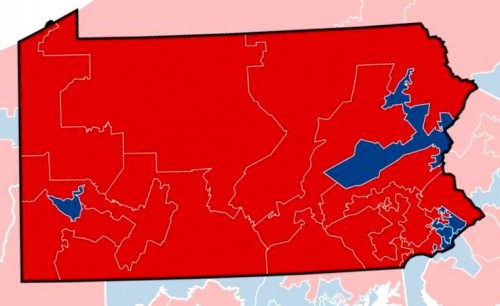

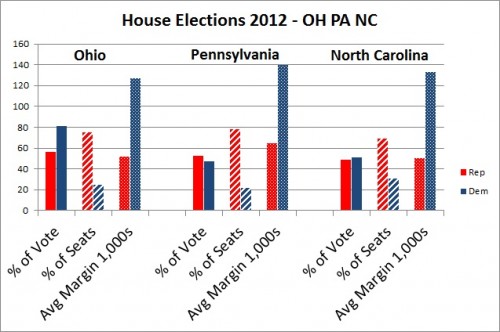

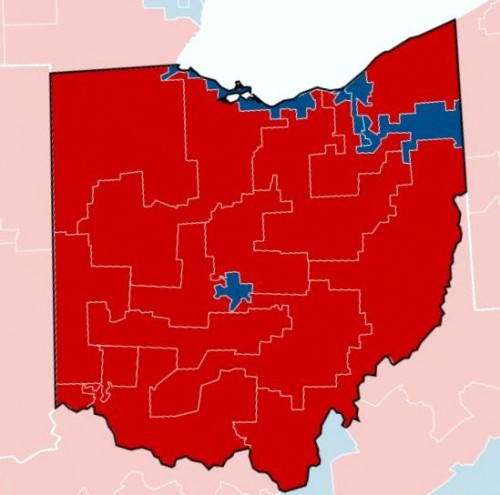

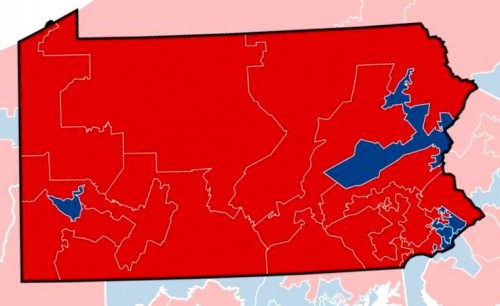

Similar differences crop up in Ohio and Pennsylvania. The popular vote is close, and in two of these states it goes to the Democrats. But Republicans get most of the seats. Republicans win their seats by less than half the margin of Democratic winners. Here is a graph of the actual returns from Ohio, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina. (The Ohio total does not include the vote from the two uncontested districts, one Democrat, one Republican. For the maps and election results, check out Politico.)

The Republican share of Congressional seats is far out of proportion to its share of the vote. In Ohio and North Carolina, Democrats received more votes, but Republicans got 70-75% of the House seats. It certainly is possible that Republican-dominated state legislatures drew the districts so as to cram Democratic voters into electoral ghettos.

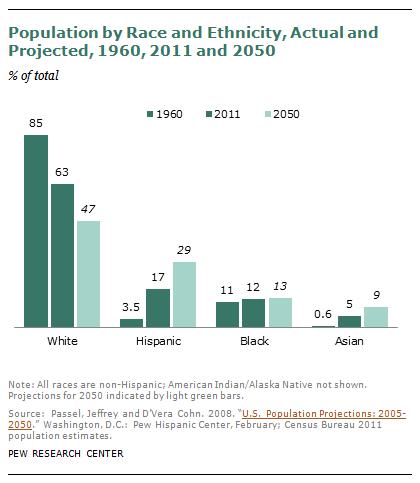

I don’t know enough about the demography and geography of these states, but I do wonder why the districts are drawn this way. A paper by Chen and Rodd (here) that uses 2000 election data argues that what looks like gerrymandering is in fact the result of “human geography.” It’s not the legislatures that pack Democrats together, it’s the Democrats themselves. They cluster in cities. As for Democrats outside of cities,

many rural, small-town, and suburban precincts that lean Democratic are often subsumed into moderately Republican districts. . . . There are isolated pockets of support for Democrats in African-American enclaves in the suburbs of big cities and in smaller towns with a history of railroad industrialization or universities. However, these Democratic pockets are generally surrounded by Republican majorities, thus wasting these Democratic votes. As a result, the Democrats are poorly situated to win districts outside of the urban core.

Regardless of intent, the effect is to keep Democratic votes concentrated in the 4th. If that blue tail of the NC-04 were subsumed into the pink NC-02, both districts might be blue.

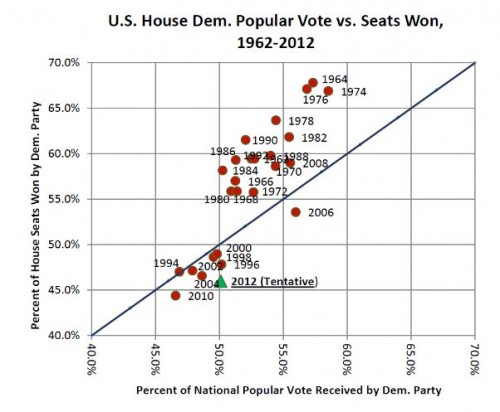

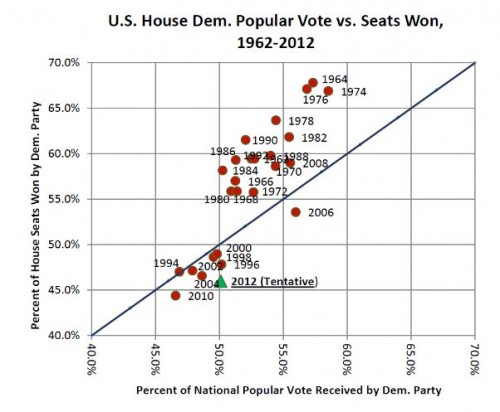

In any case, Democrats have not always been on the wrong side of the seat/vote discrepancy. John Sides at The Monkey Cage posted this graph showing the ratio for the last twenty-six elections.

Sides quotes Matthew Green on the general trends:

- the winning party usually gets a “boost” in the number of seats

- that boost used to be much larger

That trend might fit with the deliberate-gerrymander explanation, provided that in the earlier decades more state legislatures were controlled by Democrats. But I’m not sure how it fits with Chen and Rodden’s human geography idea of “unintentional gerrymandering.”

—————————

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.

In a fun five minutes, Mike Rugnetta manages to invoke John Stewart Mill and Judith Butler, plus discuss how “bronies” — male fans of My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic — challenge rigid rules of masculinity.

In a fun five minutes, Mike Rugnetta manages to invoke John Stewart Mill and Judith Butler, plus discuss how “bronies” — male fans of My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic — challenge rigid rules of masculinity.