Cross-posted at Sociology Lens.

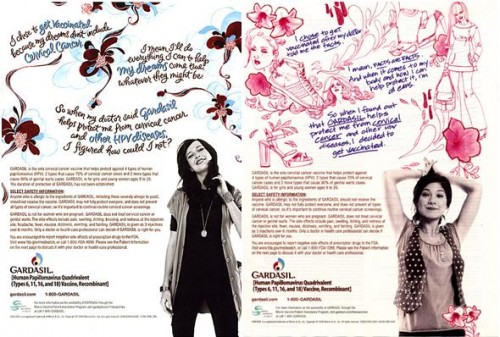

A number of researchers suggest that the marketing and advertising of Gardasil has been aimed at girls and women instead of boys and men. In this post I discuss two contradictory messages aimed at women through these advertisements.

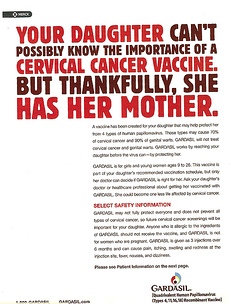

The first type of ad focused around the protection of young girls. The makers of Gardasil imply that being a good parent means vaccinating your daughter and therefore protecting her from cervical cancer (an observation also made here at Sociological Images). For example, one advertisement read, “How do you help your daughter become one less life affected by cervical cancer?” Another advertisement had a similar sentiment, stating “Your daughter can’t possibly know the importance of the cervical cancer vaccine, but thankfully, she has her mother” (source).

This narrative of protectionism is not surprising. In other contexts, like sex education debates, the discourse about adolescent sexuality, and in particular, girls’ sexuality, reveals a desire to protect their “innocence.”

The other type of ad moves away from the narrative of protectionism and focuses on empowerment and choice. One ad stated, “I chose to get vaccinated after my doctor to me the facts” (source). Another ad read, “I chose to get vaccinated because my dreams don’t include cervical cancer” (source).

Instead of focusing on the ways in which girls and women can be protected, the ads suggest that girls and women need to protect themselves. It seems like the advertising department at Merck (the makers of Gardasil) recognize that they needed another strategy if they wanted to appeal to young women who feel empowered about their sex lives.

Instead of focusing on the ways in which girls and women can be protected, the ads suggest that girls and women need to protect themselves. It seems like the advertising department at Merck (the makers of Gardasil) recognize that they needed another strategy if they wanted to appeal to young women who feel empowered about their sex lives.

These two strategies are opposed to one another. One strategy suggests that girls and women need to be protected, while the other strategy relies on the ability of girls and women to be active and educated decision makers. Merck is tapping into two gendered narratives in order to sell to as many people as possible. This is, of course, the way that advertising works. But it does reveal the different, and sometimes contradictory, cultural ideas about women’s sexuality, ideas that advertisers will draw on in order to make a profit.

—————————

Cheryl Llewellyn is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at Stony Brook University. She writes for Sociology Lens, where you can read her post about the feminization of the Gardasil.