October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month and the Boston Globe included a discussion of the pink ribbon campaign and cause-related marketing (products marketed with a promise of a donation to a social cause) more generally. It, like books by sociologists — including Samantha King’s Pink Ribbon Inc. and Gayle Sulik’s Pink Ribbon Blues — paints a pretty depressing picture of cause-related marketing.

As the article discusses, this approach to raising money for a cause is suspect for a number of reasons. In many instances, the percent of profit that goes to charity is very small. For example, one woman bought a candy bar being sold door-to-door under the auspices of a breast cancer donation, only to discover that she was invited to spent .42 cents to mail in a coupon (story here). The company would then donate one cent to breast cancer research! (And the chocolate was bad, too.)

In other instances, companies have a cap on how much they’ll donate. But consumers may or may not know that the cap is exceeded when they are in a position to buy the product. This is the case with New Balance.

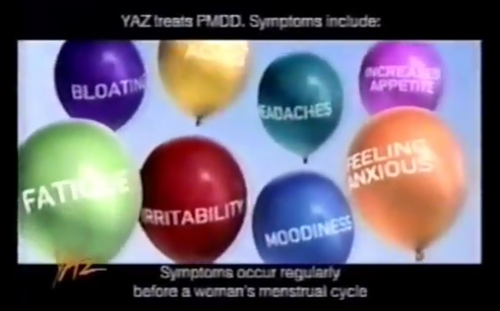

In addition, companies that participate in cause-based marketing may do so without thinking through and altering their own practices that may be contributing to rates of breast cancer. Yoplait, for example, “pinked” their yogurt for breast cancer, even as it contained milk from cows given recombinant bovine growth hormone, a substance correlated with breast cancer rates. After pressure from Breast Cancer Action, Yoplait changed its practices (Dannon followed).

This suggests that companies participating in cause-related marketing may not really be behind the cause, but may instead simply be interested in the profits. However, cause-related marketing does give advocacy organizations a wedge. If Yoplait hadn’t pinked its product, it’s unclear whether it would have felt compelled to change its ingredients. In this sense, the hypocrisy was an opportunity.

The article also introduces Jeanne Sather, who blogs about “the most egregious, tasteless examples of pink-ribbon products.” The winner of her most recent contest for the most tasteless product: Jingle Jugs, “plastic breasts mounted taxidermy-style on wood” that jiggle and bounce in response to music. They are, as you might imagine, marketed largely to frat boys (and the like) and the breast cancer edition allowed fraternities to merge their philanthropic and misogynistic tendencies seamlessly:

Jingle Jugs’ slogan: “Partnering with our nation’s youth to save our loved ones.”

Nice double entendre there.

This type of objectification of women’s bodies in breast cancer awareness advertising is common. Renée Y. sent in this advertisement for a breast cancer research fundraiser. Again, note that it says “Save a breast,” not “Save a woman’s life.”

Opponents of cause-based marketing argue that it is fraught with ethical problems and, at its worst, is deceiving and offensive. While it does result in money for the cause, it may also reduce the amount of money people donate directly because they think that by buying the breast cancer cookies, cream cheese, combination locks, cat food, cookware, chewing gum, limo rides, and golf accessories, they’ve already done their part.

Originally posted in 2009; images found here, here, and here.