Compared to the less powerful, more powerful people feel more entitled to be treated fairly, are quicker to identify an instance in which they are mistreated, and more likely to take action in response.

Compared to the less powerful, more powerful people feel more entitled to be treated fairly, are quicker to identify an instance in which they are mistreated, and more likely to take action in response.

These are the findings of a new study by social psychologist Takuya Sawaoka and colleagues. They defined power as “disproportionate control over other people’s individuals’ outcomes.” I imagine someone who is a boss, perhaps, or a police officer, professor in a classroom, or patriarch of a family, or even just people who are wealthy and can pretty much pay people to do anything they want.

The scholars review the literature showing that people with power are entitled to a disproportionate share of resources and more likely to cheat, steal, and lie. They hypothesize that this “individual variability in entitlement shapes people’s reactions to injustices that they experience” and designed a series of studies to test it.

In the first study, participants were primed to feel either powerful or powerless by being asked to write about and reflect on a situation in which they felt they had power over someone else or, alternatively, someone had power over them. They were then instructed to play a game with a confederate (unknown to them) who had ten tokens that they could divide up however they pleased. Participants who had been primed to feel low power expected to get less than half the tokens, but participants who had been primed to feel powerful expected a fair outcome.

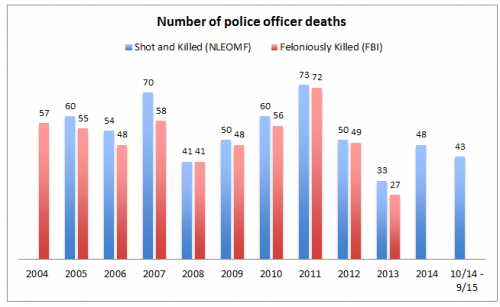

They then tested individuals’ sensitivity to unfairness. They showed people primed to feel powerful and powerless distributions of tokens that looked liked this, but with varying amounts, and asked them to indicate whether the distribution was fair or unfair.

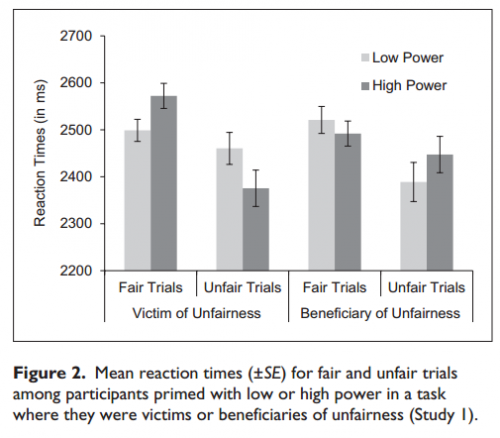

Their measure of sensitivity was how quickly the person identified the distribution as unfair. Their findings showed that, when they were the victim of unfairness (see the second pair of columns from the left), people feeling powerful were quicker to identify it as unfair (a lower bar = faster) than were people feeling powerless.

But, when they benefited from unfairness (see the pair of columns on the far right), people feeling powerful were slower to identify it as unfair than when they were the victims and slower than people who felt powerless.

They had similar findings when people primed to feel powerful didn’t directly benefit, but simply observed other people being treated unfairly. And, they tested whether their findings extended to interpersonal justice, too, by asking how people responded to being socially excluded. They found the same pattern.

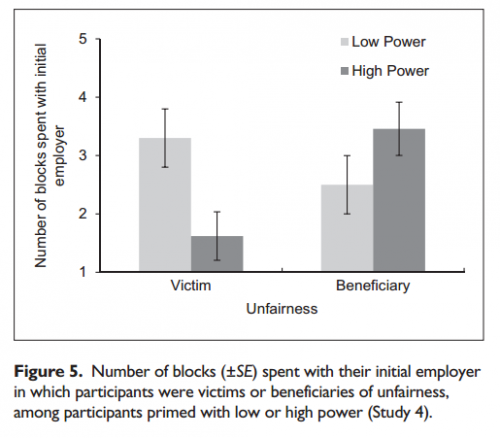

Finally, they found that, when being treated unfairly, participants primed to feel powerful were quicker to take action than those primed to feel powerless. The two columns on the left below show that high power people quickly left a hypothetical employer for a different one if they were treated unfairly.

So, to conclude, people who are primed to feel powerful feel entitled to fair treatment — both economically and socially — and are quick to recognize and correct it when they are treated unfairly, but they are significantly less likely to notice or care when the less powerful are injustice’s victims.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.