Cross-posted at Global Policy TV.

Title IX, an amendment to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, stated that “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance…” Passed on this day in 1972, this policy meant that schools and colleges receiving federal funding could not legally give preference to men. Instead, they had to allocate their resources to men and women in proportion to their interest and enrollment.

The intention of the policy was to change the norms that gave preference to men in all sorts of fields, from medical schools to sports teams. Because most schools and colleges have extensive athletics departments, sports was included among the resources that the schools were required to dole out fairly.

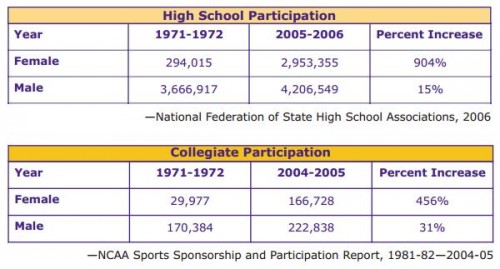

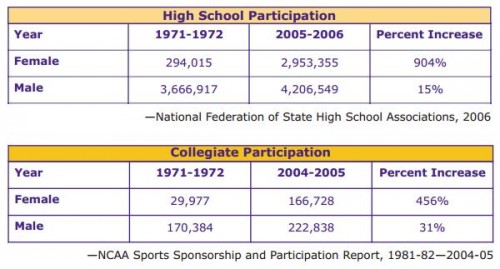

Accordingly, even grudging and partial compliance with the requirements of Title IX dramatically increased the opportunity for women to play sports. In the next 35 years, women’s participation in high school and college sports would increase by 904% and 456% respectively (source). Today, 42% of high school athletes and 45% of college athletes are women (source).

Title IX is often mistakenly accused of forcing schools to cut funding for men’s athletics. In fact, funding for men’s athletics, as well as the number of men who play sports in school, has increased since Title IX. The chart above also shows that men’s participation has increased by 15% in high school and 31% in college. It’s not true, then, that Title IX has led to fewer male athletes (especially because some colleges count men as women). Still, there is great resistance to the Amendment, with a particular emphasis on sports. Many schools are only marginally compliant, and then only because (tireless) Title IX Officers keep pressure on institutions to follow the law.

It will be fascinating to see how changing college demographics affect the politics around Title IX. After all, forty years later, people still argue that it’s not right that women’s sports get (almost) as much funding men’s. Now there are more women on college campuses than men, so proportional funding may mean spending more money on women’s sports than men’s. Fire and brimstone upon us.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.