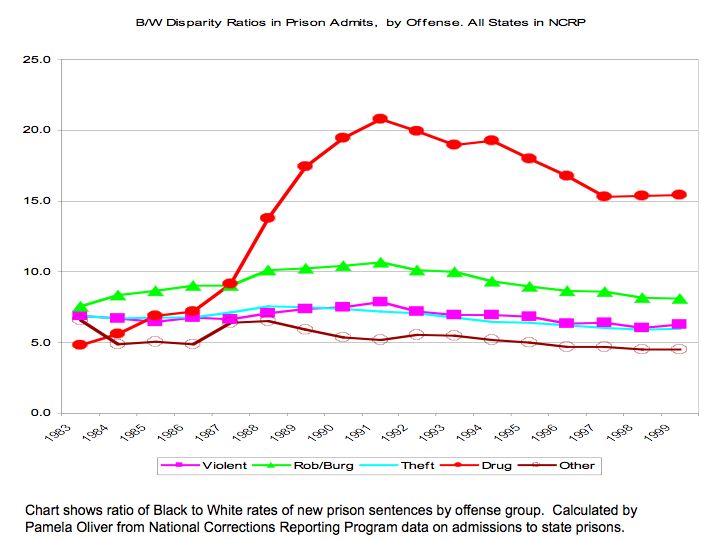

Pam Oliver sent in this graph that shows disparities in Blacks’ and Whites’ new prison sentences:

While blacks are more likely to be sentenced for all the offenses shown, clearly drug offenses stand out as the area with the biggest racial disparity in prison sentences. The other thing that stands out is the huge jump that occurred in the late 1980s and how much higher the disparity was by the 1990s than in the 1980s. Either African Americans suddenly started doing a whole lot more drugs, Whites stopped doing them altogether…or Blacks started getting arrested and sentenced at a much higher rate than Whites for drug offenses.

From an article by Oliver:

…the rise in imprisonment since the 1970s is not explained by crime rates, but by changes in policies related to crime…Determinate sentencing, which eliminates judicial discretion, longer sentences for drug offenses, increases in funding for police departments and large increases in prison capacity, the exacerbation of racial tensions and fears following the civil rights movement and the riots of the 1970s, and the politicization of crime as an election issue all seem to have played some role.

In Focus 21 (3) pp. 28-31 Spring 2001.

Other sociologists have pointed out that Whites tend to sell drugs inside buildings (houses, dorm rooms, workplaces) to people they know, while Blacks are more likely to engage in open-air sales to strangers. It’s much easier for police to see and arrest people engaged in open-air sales because they’re visible and, being out in public, can often be stopped and frisked without a warrant. Clearly it would be more difficult to know about drug sales taking place in private residences, and there would be more procedural hurdles to searching for them. And when you’re selling to strangers, you’re more likely to see to an undercover cop or to sell to people who don’t really have a problem saying who they bought their drugs from. So the very manner in which they sell makes it much more likely that Blacks will be caught and arrested, even though enormous amounts of drugs are bought and sold by Whites.

You can find a lot more graphs and articles on this topic (including disparities broken down by state) at Pam Oliver’s website. Also see this post about international imprisonment rates. Thanks, Pam!

Oh, and Lisa’s at the American Sociological Association meetings, which is why you’re stuck with just me this week.