Breck C. sent in this story in the Wall Street Journal about a study showing a link between geography and personality– that is, that different personality traits are dominant in different regions of the U.S. Personality traits were measured by answers to the Big Five Personality Test, which is widely used in psychology and other fields to determine a person’s dominant personality traits. The story was accompanied by maps showing where five traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness) are dominant. According to the study, many stereotypes, such as the neurotic East Coaster, have a basis in reality.

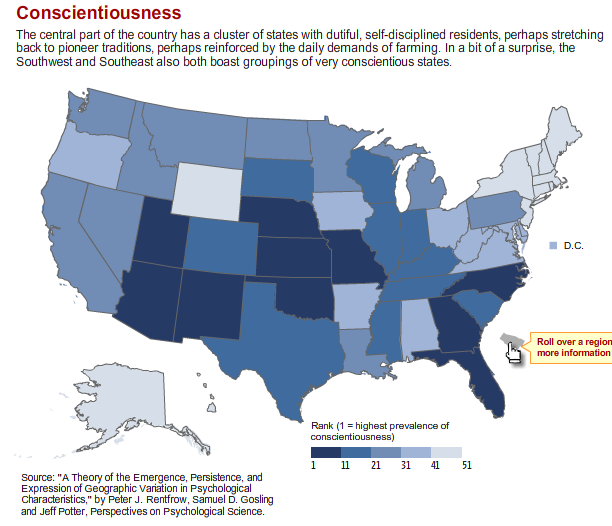

Here is a screenshot of the map of conscientiousness:

Leaving aside any questions about personality questionnaires, and whether people are very accurate at reporting their own personality traits, what I found interesting here is the explanation of this pattern in the caption above the map (which I’m assuming was written by someone at the WSJ and didn’t come from the study): perhaps the Great Plains region is conscientious because of “pioneer traditions” reinforced by “the daily demands of farming.” On the other hand, it’s “surprising” that people in the Southwest and Southeast would be conscientious.

This is a great example of a non-scientific explanation of data that relies more on stereotypes and assumptions than anything else. Why would pioneer traditions be any stronger in Kansas and Missouri than in Oregon or Montana (or a number of other states) that were also settled by “pioneers” (however you want to define that term)? I’m unclear whether the reference to farming is meant to describe the past or the present, but either way, it’s suspect. Lots of other states (including those surprisingly conscientious states in the Southwest and Southeast and many of the less conscientious states) have farming traditions, as well as important agricultural sectors today (like, say, Iowa and its corn). The vast majority of people in those conscientious states aren’t engaged in agriculture today. And for that matter, why would the “demands of farming” lead to conscientiousness in a way that other types of work wouldn’t? These seems to play on stereotypes of farmers (and rural folk more generally) as hard-working, honest, salt-of-the-earth types, compared to superficial, rude (but hipper) city dwellers.

It’s the type of unsophisticated, stereotypical interpretation of academic studies that I often see in the media, and I think this particular explanation of why these states would be conscientious is just silly.

Thanks for the link, Breck!