Sociologists Martin Weinberg and Colin Williams wanted to know. They and their team interviewed 172 college students about their habits and concerns about farting and pooping. They published their results in an article called Fecal Matters. They discovered that everybody farts and everybody cares, but not everyone cares all the time or equally.

Sociologists Martin Weinberg and Colin Williams wanted to know. They and their team interviewed 172 college students about their habits and concerns about farting and pooping. They published their results in an article called Fecal Matters. They discovered that everybody farts and everybody cares, but not everyone cares all the time or equally.

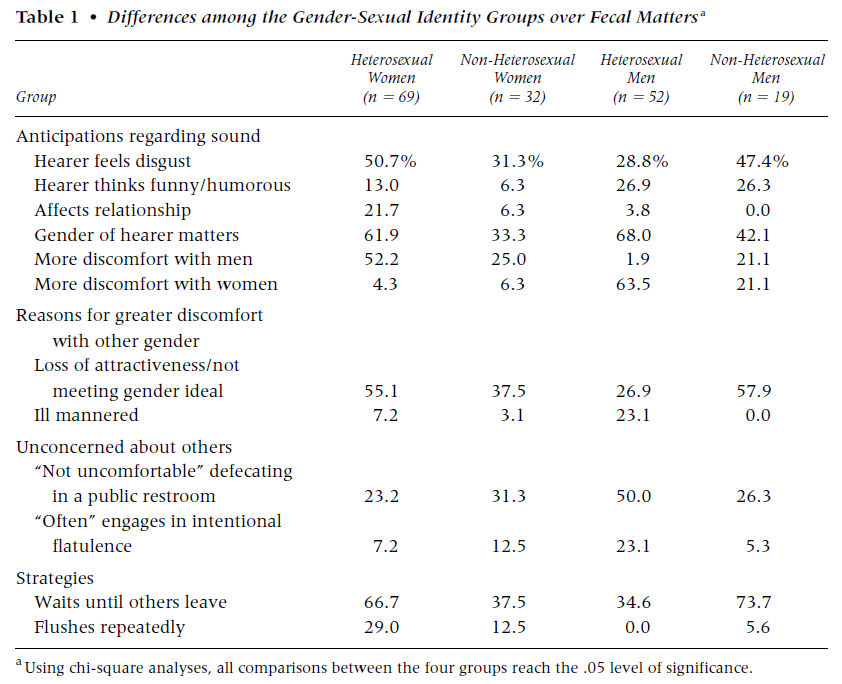

They separated their results by gender and sexual orientation. When they asked people if they were worried that the hearer would “feel disgust,” heterosexual women were most likely to agree and heterosexual men the least, with non-heterosexual men and women in the middle, but flipped such that men were more worried than women.

Heterosexual men were the most likely to think it was funny and the most likely to engage in “intentional flatulence.” Almost a quarter said that they “often” did so, whereas only 7 percent of heterosexual women said the same. “Guys would say it’s raunchy and then say ‘Nice one,’” explained one heterosexual guy, “because if it’s strong it’s more manly. You know, because women would not try to clear a room with a fart.” Heterosexual women felt like they were violating gender norms if their farts were stinky: “The worse it stinks,” said one, “the nastier they think I am.”

Heterosexual women were the most concerned that it would affect their relationship with the hearer. They were also the most likely to do things to reduce the likelihood that others would detect their bathroom activities, like go into another room to pass gas or let their stool out slowly to avoid a kerplunk. Two thirds said they would wait until they were alone to poop and only women reported flushing repeatedly to ensure that the sights and smells of their defecation had disappeared.

As a counter example, one of the heterosexual men interviewed said that the only thing he was willing to do to protect others from his bathroom activities was close the door.

Non-heterosexual men were an interesting conundrum. They were as likely as heterosexual men to think that the hearer would think it was funny, but the least likely to engage in intentional flatulence and the most likely to make sure that when they poop, they do so alone.

Non-heterosexual women were also a conundrum. They were the least likely to think the hearer would laugh at a fart, but second only to heterosexual men in the practice of farting on purpose to get a reaction.

This study is a great example of what social scientists call doing gender, modifying our behavior to conform to gendered expectations. Generally, women are expected to have better control of their body, to be more polite, and to avoid offending others. All of these things are consistent with being more discreet with farts and poops.

The interesting data from non-heterosexual men and women may be explained by the conflation of sexual object choice and the performance of gender. It’s not universally this way, but in the U.S. today gay men are feminized and lesbians masculinized. This is a stereotype, but also gives non-heterosexual men and women some permission to deviate from gender rules. As one non-heterosexual man explained:

Only around people that I’m regularly naked with would I be comfortable with them knowing what I was doing in the bathroom. I’m on the self-prescribed “pretty pill”—where you don’t fart, sweat, burp, or use the bathroom… I learned it from my diva friends.

Similarly, some non-heterosexual women may feel a little less pressure to be as girly or girly all the time.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.