Originally Posted at TSP Discoveries

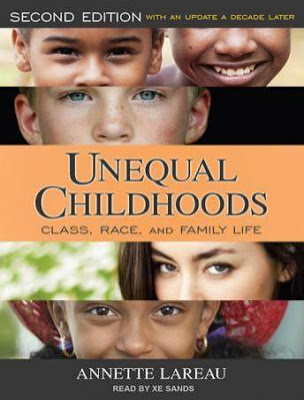

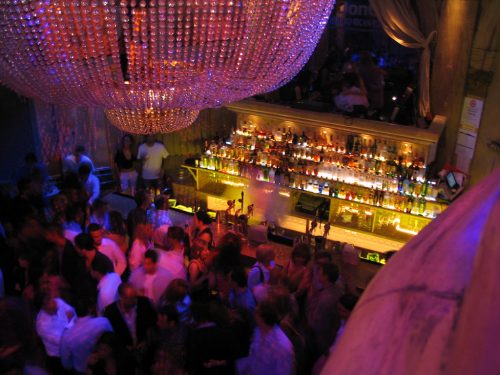

Whether we wear stilettos or flats, jeans or dress clothes, our clothing can allow or deny us access to certain social spaces, like a nightclub. Yet, institutional dress codes that dictate who can and cannot wear certain items of clothing target some marginalized communities more than others. For example, recent reports of bouncers denying Black patrons from nightclubs prompted Reuben A Buford May and Pat Rubio Goldsmith to test whether urban nightclubs in Texas deny entrance for Black and Latino men through discriminatory dress code policies.

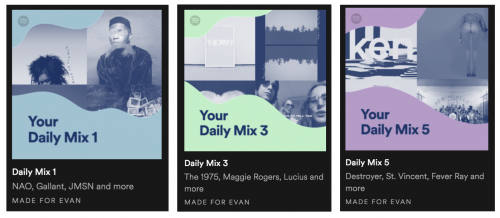

For the study, recently published in Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, The authors recruited six men between the ages of 21 and 23. They selected three pairs of men by race — White, Black, and Latino — to attend 53 urban nightclubs in Dallas, Houston, and Austin. Each pair shared similar racial, socioeconomic, and physical characteristics. One individual from each pair dressed as a “conformist,” wearing Ralph Lauren polos, casual shoes, and nice jeans that adhered to the club’s dress code. The other individual dressed in stereotypically urban dress, wearing “sneakers, blue jean pants, colored T-shirt, hoodie, and a long necklace with a medallion.” The authors categorized an interaction as discrimination if a bouncer denied a patron entrance based on his dress or if the bouncer enforced particular dress code rules, such as telling a patron to tuck in their necklace. Each pair attended the same nightclub at peak hours three to ten minutes apart. The researchers exchanged text messages with each pair to document any denials or accommodations.

Black men were denied entrance into nightclubs 11.3 percent of the time (six times), while White and Latino men were both denied entry 5.7 percent of the time (three times). Bouncers claimed the Black patrons were denied entry because of their clothing, despite allowing similarly dressed White and Latino men to enter. Even when bouncers did not deny entrance, they demanded that patrons tuck in their necklaces to accommodate nightclub policy. This occurred two times for Black men, three times for Latino men, and one time for White men. Overall, Black men encountered more discriminatory experiences from nightclub bouncers, highlighting how institutions continue to police Black bodies through seemingly race-neutral rules and regulations.

Amber Joy is a PhD student in sociology at the University of Minnesota. Her current research interests include punishment, sexual violence and the intersections of race, gender, age, and sexuality. Her work examines how state institutions construct youth victimization.