In her excellent article “Invisible Inequality: Social Class and Childrearing in Black Families and White Families,” Annette Lareau looks at differences in childrearing strategies, finding that class differences were more important than racial differences. Lareau argued that childrearing methods are one way in which class-based advantages are reproduced. Middle-class parents use a “concerted cultivation” model, which involved high levels of involvement in extracurricular activities. Working-class parents engaged in what Lareau calls an “accomplishment of natural growth” model, which emphasizes loving children and providing for them and giving children much more leisure time that is self-directed and unstructured. As Lareau writes,

Working-class and poor children spent most of their free time in informal play; middle-class children took part in many adult-organized activities designed to develop their individual talents and interests. (p. 761).

There are downsides to the concerted cultivation model. The range of activities children are involved in “dominate family life and create enormous labor, particularly for mothers” (p. 748). The emphasis on organized activities led to generally weak family ties, as well as weak social ties more generally, since they were based on participation in activities (extracurricular sports, classes, etc.) that have high turnover rates in membership and often last a few weeks regardless. However, Lareau argues that the concerted cultivation model ultimately transmits class advantages, given that the behaviors and assumptions it socializes children into prepare them well for a social world dominated by other middle-class professionals. And she argues that these different models are not just based on preferences; existing class inequalities make it much more difficult for working-class parents to follow the concerted cultivation model:

Enrollment fees that middle-class parents dismissed as “negligible” were formidable expenses for less affluent families…Moreover, families needed reliable private transportation and flexible work schedules to get children to and from events. These resources were disproportionately concentrated in middle-class families. (p. 771)

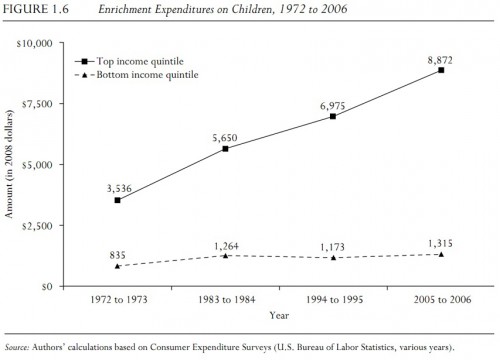

The Russel Sage foundation recently posted a graph that highlights class differences in spending on activities and products meant to aid child development, learning, and general enrichment. The graph, from Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances, shows how the gap in spending on such items — which includes things such as tutoring, private schooling, summer camps, high-quality childcare, and computers — has grown between the poorest and wealthiest Americans in recent decades, illustrating Lareau’s argument about differential access to the products and activities central to the concerted cultivation model:

Full cites:

Greg J. Duncan and Richard J. Murnane. 2011. Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances, ed. Greg Duncan and Richard Murnane. NY: Russell Sage. [Graph from p. 11.]

Annette Lareau. 2002. “Invisible Inequality: Social Class and Childrearing in Black Families and White Families.” American Sociological Review 67(5): 747-776.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.