In a classic piece on community-based learning (CBL) in sociology, Mooney and Edwards define CBL as a broad term that incorporates many kinds of educational experiences that move students into the larger community or bring the community into the classroom. CBL in the classroom has shown to be valuable in connecting social realities to individual experiences and helps “develop increased political awareness, leadership skills, and civic literacy.”

While well intentioned, many have documented how CBL inadvertently reinforces unequal power dynamics when students are seen as providing a “service” to less privileged communities, when the needs of community partners are not properly considered and CBL creates additional burdens. With these benefits and critiques in mind, I decided to try a small-scale version of CBL by inviting a community advocate, a specialist from a local diaper bank that addresses diaper needs in the greater community, to conduct a guest lecture in my Sociology of Family course at the University of Georgia. Establishing trust between the instructor and community partner is critical to the success of incorporating CBL in the classroom. I was careful to engage the community advocate in a meaningful conversation beforehand, so that I could ensure that both the students and the community organization were benefitting from the visit. During our phone conversation beforehand, the community advocate relayed her excitement about the opportunity to educate my students and informed me of the ways in which the diaper bank benefits from this outreach (developing relationships, recruiting volunteers and possible internships).

The class I teach is an upper-level course focused on using a sociological approach to studying the institution of the family and draws Sociology, Human Development, and Family Science students.

I had three goals in mind for the visit: I wanted to provide a real-world example of how societal factors influence parenting abilities and decisions, give space in my class to a community actor who is immersed in the work, and present my students with a clear and accessible pathway to get involved in a solution. To prepare for our session, I assigned students a brief article published in Contexts that defines diaper need and describes how class blindness works to make the societal failures invisible.

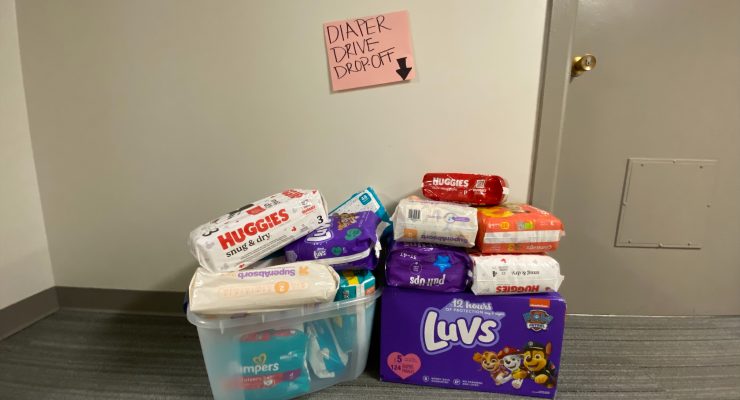

During the visit, the community advocate provided students with examples that demonstrated the very real consequences that parents in their own community are facing. After she spoke specifically about the bank’s mission, the class engaged in a deeper discussion about the inequalities that perpetuate diaper needs and disparities and the societal stigma that parents face. This led to the burning question from students, “What can we do?” Students lined up to talk to her after class, asking about volunteer and internship opportunities. The students and I together decided to host a class diaper drive, which resulted in the collection of 579 diapers to donate. I was most struck by the initiative students continued to take outside of the class afterwards, planning their own diaper drives.

This experience was an example of CBL on a small scale. As I continue to experiment with CBL I think that increasing the stakes slightly, (e.g., having students visit or work with the bank) might deepen student learning. In the future I might also discuss the price of diapers, and incorporate a component in which students can talk about the experience of buying diapers, and how this experience is influenced by their social location.

Shelby L. Clark is a doctoral candidate in the Sociology Department at the University of Georgia. She has taught courses on the Sociology of Family, Sociology of Gender, and Research Methods.

Comments