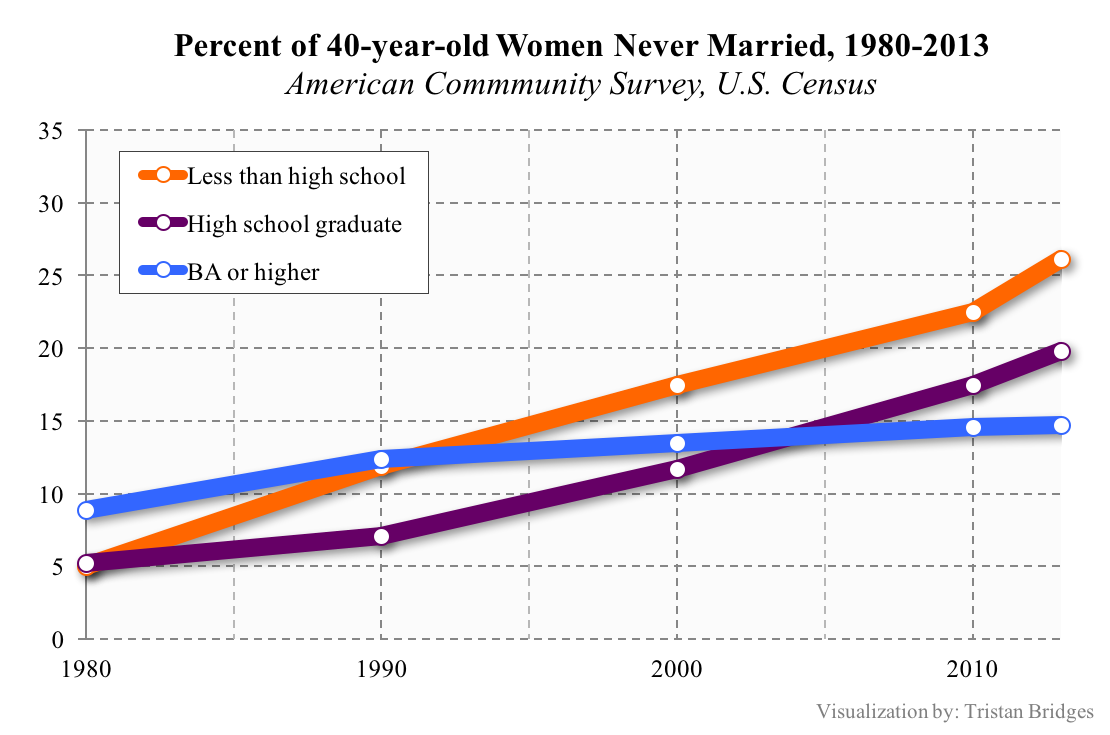

The situation. Americans are delaying and foregoing marriage in larger numbers than they used to. In 1980, about 5% of 40-year-old women with only a high school education or less had never been married. Almost 9% of 40-year-old women with at least a BA had never married. And these numbers have been rising for all of these groups, some more than others. It’s all the more interesting because, in this same time period, marriage has become legally accessible to more individuals. But, by 2013, the proportions of 40-year-old women who had never married exploded (see graph below*). There are a variety of reasons that account for this shift. At a basic level, women are getting more education and have more life options than they did 30+ years ago. But are heterosexual women foregoing marriage altogether, or are they still waiting for “Mr. Right”? And if they’re waiting, are there enough Mr. Rights to go around?

The man question. With the rise of women’s options not to marry, no wonder questioning men’s status as “marriage material” is pervasive in popular culture. This “man question” is so accepted that further elaboration is not typically required when suggesting an individual man fails to pass muster. But, sociologists take the idea seriously. We have examined three decades of research to demonstrate the rise of the man question—and the ways it relates both to rising gender equality and economic inequality.

Marriageability = jobs? In the late 1980s, sociologist William Julius Wilson sought to give the phenomenon a social scientific name and a more precise and measurable quality. Wilson studied poor and working-class communities and discovered that inner-city joblessness among lower-income black men was resulting in a dilemma for inner-city lower-income black women: a growing shortage of men who might qualify as marriageable. Since the majority of marriages and relationships in the U.S. (both then and now) are between people with similar class and racial backgrounds, this extended the gap even further.

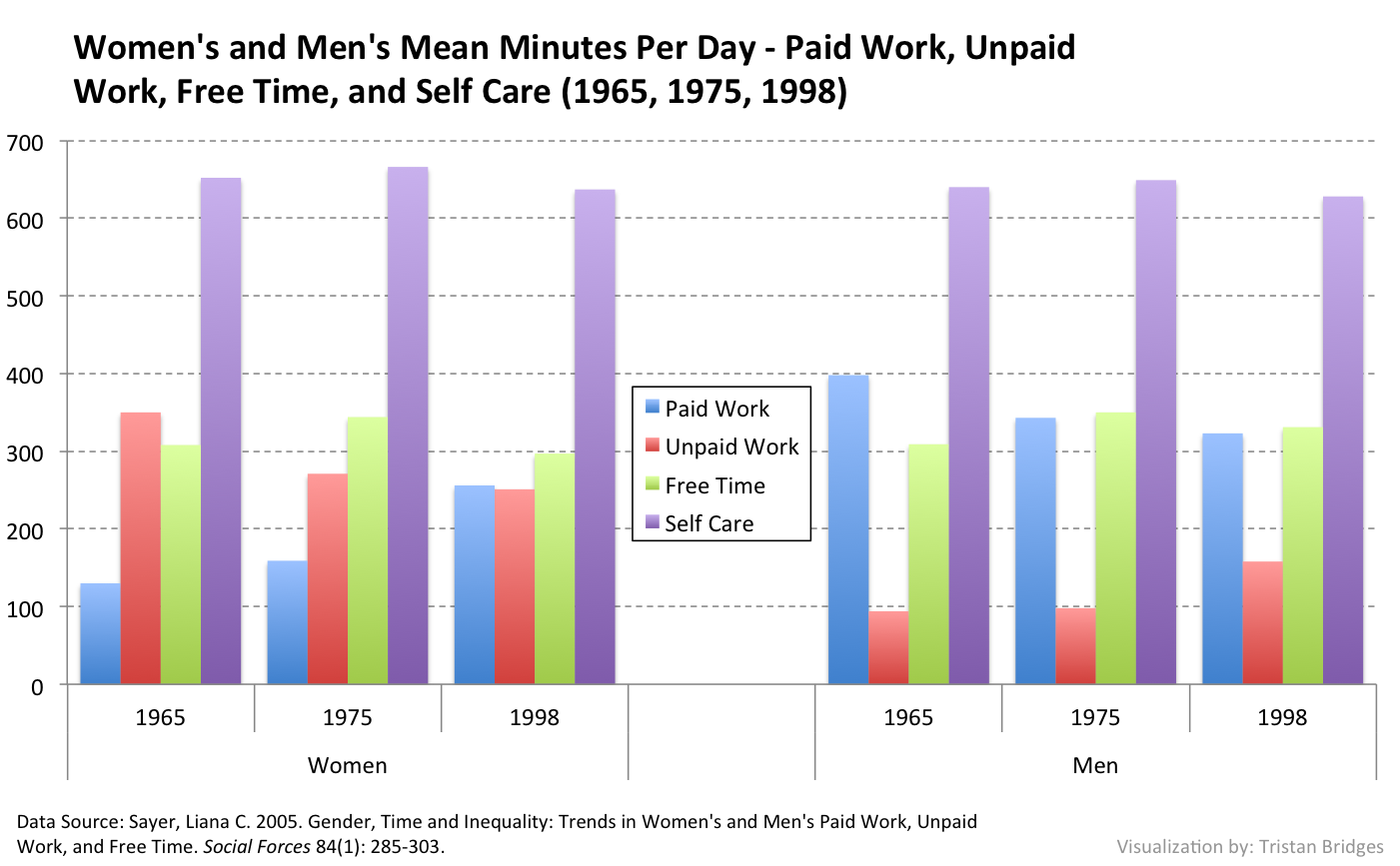

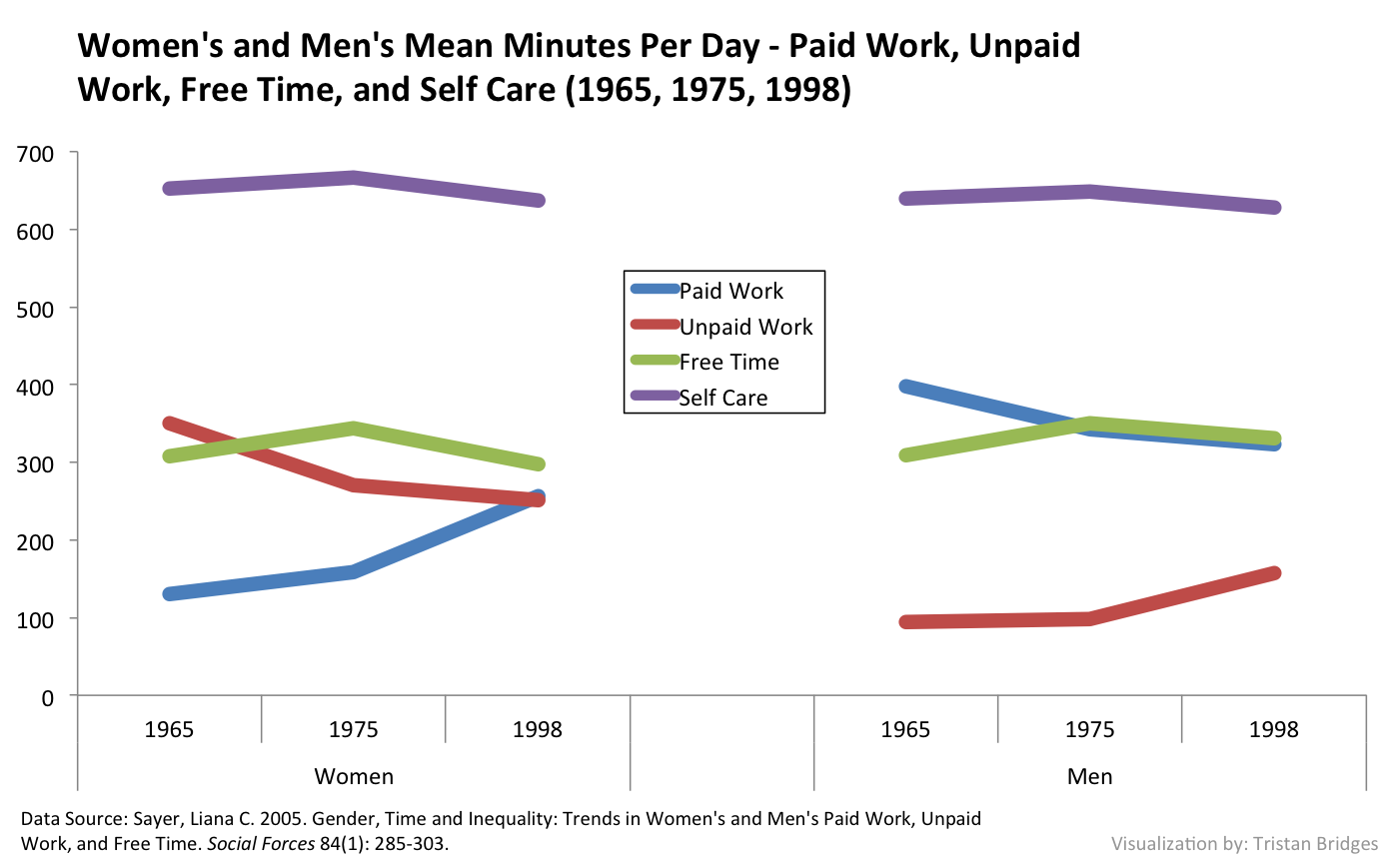

Wilson defined men’s “marriageability” in terms of economic stability. Employment was key, in his view, to men’s suitability as marital partners. Changes in the economy in the prior several decades had produced ripple effects that left fewer men in this group able to find gainful employment. And these problems still exist. Using education as a proxy for class status, lower-income heterosexual women still face a pool of marriageable men that is too small for them to all find husbands. In fact, the data above suggest that it may very well be a problem that has gotten worse, particularly for Black Americans. In recent times, we have seen returns to higher education for Black women increase at a modest rate, while Black college educated men’s returns have actually declined. And the lack of employment for those without a college degree—which is hard to obtain for both Black men and women—has become more difficult for Black men. This means fewer and fewer men match women in terms of education, jobs, and other social class characteristics.

But who is thinking about men as more than a pay check? Wilson’s suggestion that too many lower-class men are not really marriage material because of the job market produced a stream of research on how lower-income women are navigating this challenging terrain. In the 1990s, the use of economic stability as the primary measure of “marriageability” received little push-back from other scholars. Few scholars, for instance, have sought to examine men’s marriageability outside of lower-income groups. And from the graph above, you can see that less educated women’s rates of never marrying have increased much more than more educated women’s. But, are middle- and upper-class women measuring men by the same yardstick? And if so, how do they measure up?

We examined over thirty years of research from 1984 – 2015. Our overview confirmed that “marriageability” research that emphasizes men’s value as a paycheck focuses exclusively on lower income groups of women and neglects the ways that women across the class divide may struggle finding “marriageable” men, but perhaps for different reasons. Our overview confirmed that “marriageability” research neglects a consideration of more complex measures than economic stability and is limited to research examining the lower-class. We suggest that scholars begin to ask about men’s “marriageability” across the class divide.

If it is about jobs, why are middle class men subject to the marriageable man question? Existing research suggests that the yardsticks for working class and middle class men are distinct—but maybe not in the way you’d expect. Our review of the research shows that while lower-income men often fail to measure up as a result of joblessness, substance abuse, and incarceration (all issues which negatively impact their employment), middle- and upper-class men able to find employment are not always understood as marriageable. Data from online dating sites like OkCupid.com illustrate this issue, too. In online dating profiles, straight men are much more likely than straight women to list words associated with jobs and professions (assuming these are the qualities women are looking for). But, as studies of middle- and upper-class women show, that just isn’t enough. These women’s understandings of what qualifies as a “marriageable” man goes beyond a paycheck—it has to do with relationship quality and equality as well.

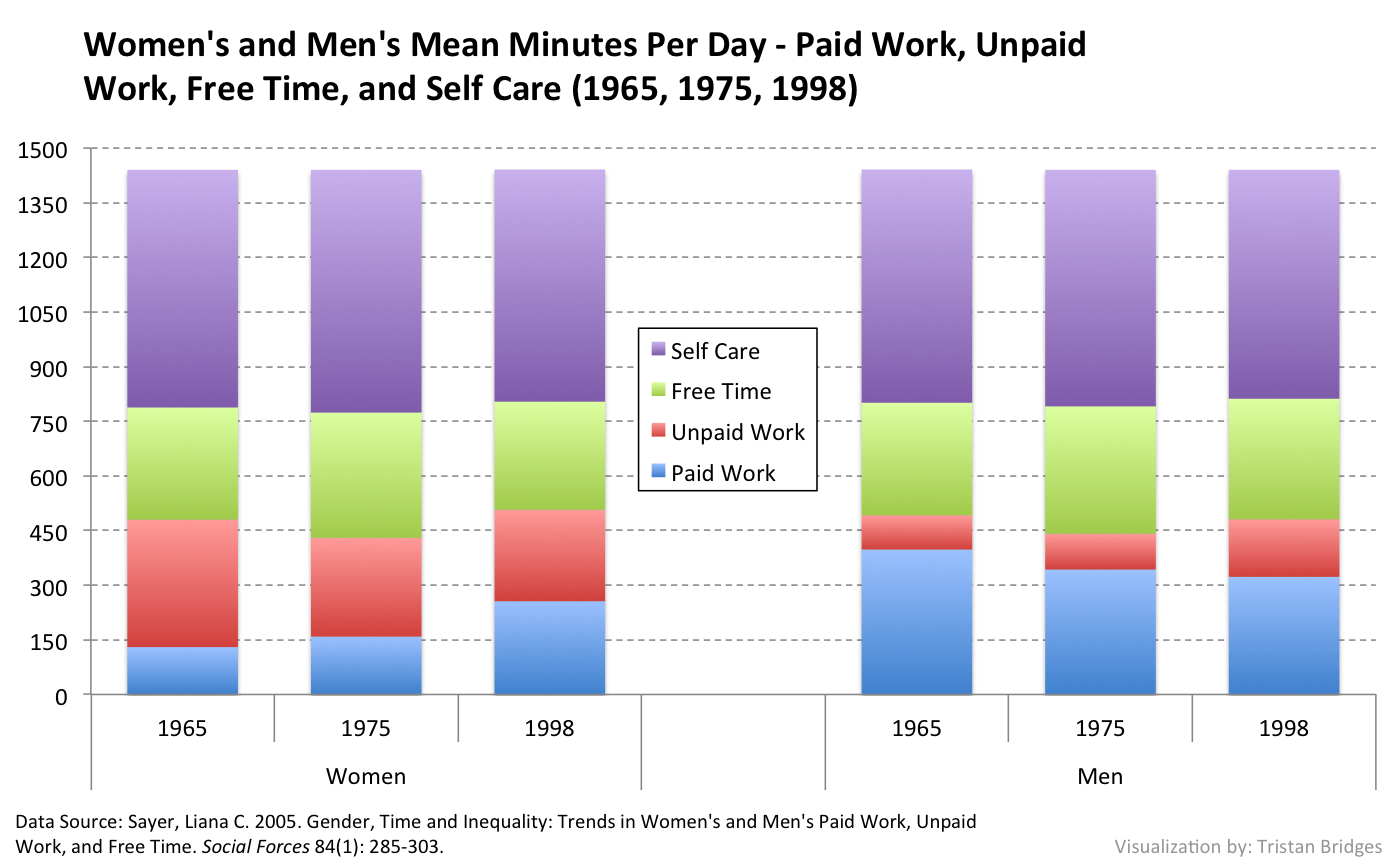

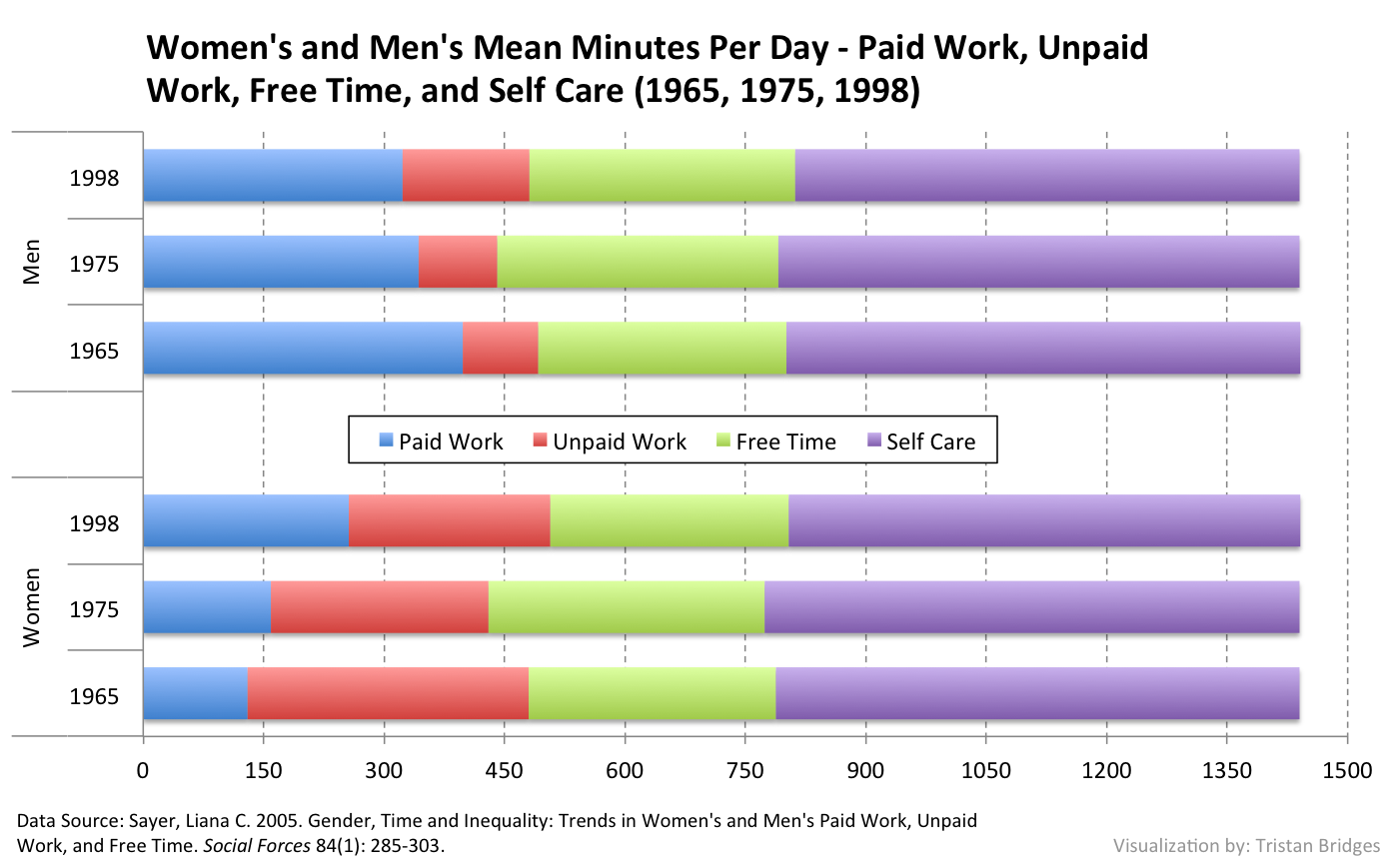

Meanwhile, women’s expectations for their relationships have transformed across the class divide. Women want more out of marriage. Many still want the economic security associated with marital households, though women today may not need to lean on this security as much as they did thirty years ago. But, they also want a set of intangibles that is much more related to the quality of the relationship than the individual qualities any given man might possess. High quality relationships provide economic support, but they also come with emotional support, shared commitments to household labor, childcare, and more. They want a partner in every sense of the word. And within this transformation, men of different class backgrounds are failing to prove themselves “marriageable”—but not necessarily for the same reasons.

For instance, research shows that in the face of economic constraints that make the breadwinner model unattainable to many working-class and poor fathers, they are redefining this role to prioritize what they can and do bring to the table—a more involved form of parenthood. Ironically, this kind of relational fathering sounds like what many middle- and upper-class women with children or desiring children say they want more of from their partners. Middle- and upper-class fathers, however, end up prioritizing the paycheck and minimizing parenting involvement due primarily to workplace policies and constraints. Many lower-income men fail by the old metric—income. But research suggests that in some ways, they fulfill many women’s desires for egalitarian relationships. Conversely, middle- and upper-income men are more likely to qualify as “marriageable” by the old metric (income), but fail by new egalitarian standards for relationships—relationships both women and men claim to desire.

Men’s “marriageability” is best understood, we find, in the context of two trends: increasing expectations of gender equality among both women and men and growing economic inequality and insecurity. Research shows that these twin trends make egalitarian relationships and marriages available to relatively few. Wilson used income as synonymous with marriageability; a steady and reliable paycheck was all men needed. But, marriageability is more complex than that. Today, income is more of a baseline expectation for consideration. And research suggests that some men may be prizing these qualities in themselves to the detriment of things that women might actually want from them.

____________________________

Thanks to Virginia Rutter for advanced comments on this draft (a while ago).

*Thanks to Philip Cohen for the data.

Acker’s short 6-page article was published in the same journal that had published Raewyn Connell’s article,

Acker’s short 6-page article was published in the same journal that had published Raewyn Connell’s article,

don’t feel constrained by their mission to help, but rather are moved to choose jobs based on their individual intellectual curiosities. I am confident that if giving back is in their heart, then they will find a way to help people by becoming social workers, teachers, attorneys, doctors, engineers, chemists, or graphic designers. So, my dear students, be selfish. And while you are at it, do your best in whatever field you choose. I’m sure you will positively impact a life or two or more along the way.

don’t feel constrained by their mission to help, but rather are moved to choose jobs based on their individual intellectual curiosities. I am confident that if giving back is in their heart, then they will find a way to help people by becoming social workers, teachers, attorneys, doctors, engineers, chemists, or graphic designers. So, my dear students, be selfish. And while you are at it, do your best in whatever field you choose. I’m sure you will positively impact a life or two or more along the way.

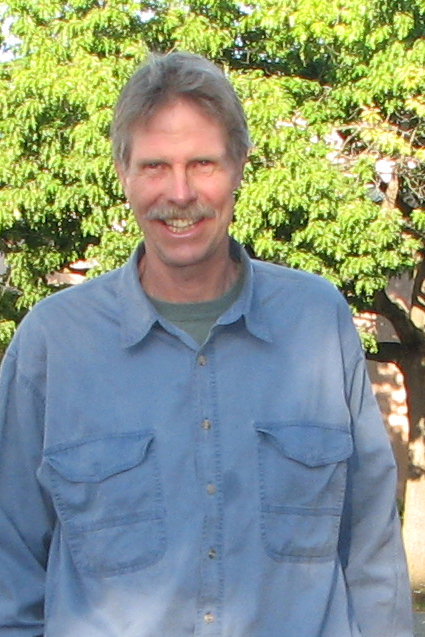

Of course, I thought of Chris Norton and MASV. I located Chris online. Ever generous, he agreed to be interviewed. In December of 2010, I drove to his house in Sebastopol, and as I knocked on his door, I wondered how different he’d look or be. After all, I had morphed from a long-haired, bearded youngster thirty years ago to clean-shaven gray-haired, gradually balding, stooped-shouldered guy. I spied him through the window as he came to the door, and as he opened it I was mildly astonished to see that he looked pretty much the same—bristly mustache and full head of hair—reddish, but with some gray mixed in. He also still had the same warm smile, accented now by smile lines around his eyes that, if anything, made him appear even more warm and friendly than before.

Of course, I thought of Chris Norton and MASV. I located Chris online. Ever generous, he agreed to be interviewed. In December of 2010, I drove to his house in Sebastopol, and as I knocked on his door, I wondered how different he’d look or be. After all, I had morphed from a long-haired, bearded youngster thirty years ago to clean-shaven gray-haired, gradually balding, stooped-shouldered guy. I spied him through the window as he came to the door, and as he opened it I was mildly astonished to see that he looked pretty much the same—bristly mustache and full head of hair—reddish, but with some gray mixed in. He also still had the same warm smile, accented now by smile lines around his eyes that, if anything, made him appear even more warm and friendly than before. Michael A. Messner

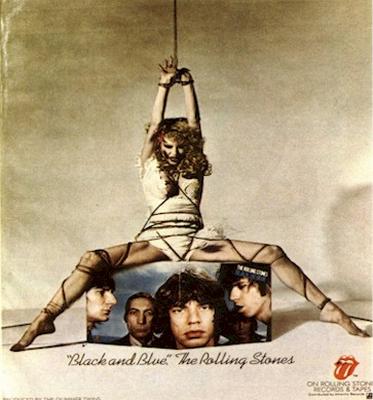

Michael A. Messner Backed up with a slideshow that depicted popular album covers (The misogynist public billboard promoting The Rolling Stones’ album Black and Blue was one of them), he pointed to the links between sexual objectification of women, men’s use of pornography, and men’s violence against women.

Backed up with a slideshow that depicted popular album covers (The misogynist public billboard promoting The Rolling Stones’ album Black and Blue was one of them), he pointed to the links between sexual objectification of women, men’s use of pornography, and men’s violence against women.