I remember, about a decade ago, meeting U.S. scholars at an international conference. In the period of an otherwise nice lunch, one particular colleague – a second wave (cisgender, straight) feminist of color – initiated a conversation on what turned out to be her nephew going through gender reassignment (although she voiced this as her “niece” going through “bodily mutilation”). I remember the challenge of having to articulate a harsh and yet loving criticism of this colleague who I otherwise respected, and still respect today, and my need to understand how, and why, these readings of the flesh took center stage in this colleague’s fears. Having experienced racialized sexualities and racialized gendered readings throughout our lives, she came to the table with preconceived notions about the sanctity of one’s body, and trans* identities and experiences challenged that idea.

About 10 days ago, I recalled that moment when I started reading criticisms of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s recent comments, and various responses from transwomen, among them Laverne Cox. Adichie has clarified her points most recently, where she reiterated the main premise of the separation between trans* and cisgender women – that transwomen have had “male privilege,” inserting, pretty much god-like, that posture on transwomen’s histories (please read this inspiring story on the challenges this poses to cisgender women agreeing with Adichie). This has been the point of contention of much of the public debate. The character of her accusations as transphobic are two-fold. On the one hand, they are politically efficacious for trans communities – a group that should be directly speaking on trans* issues (and not Adichie). Yet, on the other hand, they are a shallow move that avoids addressing the historically charged relationship between feminist thought, sociology, and trans* rights, a move that cannot be brushed away with a mere accusation of transphobia.

My goal is to converse with (cisgender and trans*/transsexual) feminist scholars and activists, and although I center my remarks on the sociological discipline, I want to reach social scientists and non-academics alike. I wish to engage whatever politics we activate when we deploy a monolithic view of feminism, but also, the subsequent attacks and remarks of Adichie as transphobic. To be sure, cisgender (straight and lesbian identified) feminist wars have taken shape for decades: as a case in point, Cherríe Moraga’s work has been critiqued for its posture against transmen (in ways that have been labeled transphobic). True, there is a lot of tension in the sex-gender wars between cisgender feminist activists/scholars, and those of latter waves of feminist thought. But what seems problematic in this case is the focus on Adichie as a target.

It seems so easy, so self-celebratory, to challenge a woman whose engagement with “third-world” postcolonial writing has been exponentially far more advanced than White cisgender feminists in the US, a scholar whose premise has been one of liberation. This, especially when there are feminists with a stronger platform – and many more untapped issues on intersectionality to address – than Adichie. Thus, I remain suspect of the inherent colonial underpinnings of those (White, well intended, trans* and cisgender activists) accusing a Nigerian woman of transphobia, in light of how Nigeria, and other countries in the African continent, are portrayed in terms of their perceived more homophobic/transphobic stands. (How much does that stance caters to USAmericans’ elevated sense of righteousness?) That, too, has to be a point of contention, and one to focus on, and work through, in these discussions.

The context of the interview is often missing from the criticisms. Ironically, and literally a minute before the oft-quoted excerpt, Chimamanda was critiquing the cliquish way (think social movements) in which left-ist groups (say: feminist groups, but let’s extend it to queer groups, anti-racist groups, “radical” groups, etc.) organize, develop a common language, solidify boundaries, and consequently police each other in terms of the maintenance of the most progressive language. She acknowledged it as a genuine attempt to create social justice and change, yes, but with the (often) unintended effect of sustaining their status.

Certainly, sociologists such as Viviane Namaste (in her book, Oversight) have critiqued these in-group linguistic privileged cues/behavior. In the context of gender-neutral language, Namaste problematizes the use of requesting self-pronouns in group setting introductions, when attempting to provide voice to a diverse set of experiences. Namaste critiques these moves for what they do – further alienating trans* and transsexual people by magnifying the White savior (cisgender and straight) complex in the utterance of the “preferred” pronouns. (Really, some do not have preferred, but their own, pronouns, defined by them and articulated in everyday interactions, and not in mere utterances.) To expect many trans (especially non-gender queer transgender and transsexual) people to unequivocally utter their identity – which has been for many a source of stress and an identity in process – and turn it around to make it seem liberating, only benefits the ones evoking its use. Ultimately, is the language we use a tool for freedom, or is language a set of exclusionary layered accounts that, by virtue of its precision, erase and dismiss those who are not “engaged” enough?

Beyond Adichie’s interview, but including it, we also fail to account for the imagery, and imaginaries, we (in US society) hold of trans people (this includes the reaction cisgender feminist women – including Adichie – often have of transwomen). In the US, most USAmericans are still more exposed to Caitlyn Jenner as a trans figure, and not so much to people like actress Laverne Cox, writer Janet Mock, or Jennicet Gutiérrez, the trans Latina activist who challenged Obama to free those undocumented immigrants in detention centers at the cusp of same sex marriage becoming legal nation-wide. (The fact that I find myself in need to add qualifiers for each of them may signal that they are not yet recognized in many places outside of these cliquish groups.) Transgender imaginaries dominate certain narratives, and Jenner’s centrality in the “reality” TV shows signals a protagonism in the US’ mainstream imagery of transwomen.

This take on transwomen’s histories, however, may also speak to the US’ obsession with power through masculinity. That tired old narrative – that Jenner renounced masculinity (after being recognized as an incredibly talented male athlete) – is still, for most USAmericans, a “shocking” narrative. Overall, such readings reveal how we conceive of power, how much we cling to it, and how little do we think of the non-masculine (or give it space, for that matter) in the world.

As another case in point, Joanne Meyerowitz documented the “former GI turned beauty queen” 1950s “bombshell transformation” – about Christine Jorgensen – in her incredibly resourceful book How Sex Changed. (Cox references Jorgensen in her tweets by mentioning the lack of recognition of transwomen, except in the “macho guy becomes a woman” pre-fixed recipe framework.) There, the focus on masculinity – a conflation of maleness and masculinity, really – is an example of the type of obsession with maleness, masculinity, and other axes of power that are often not interrogated when studied from some humanities and fields in the social sciences, and automatically plopped as a convenient narrative to explain away the “outliers.” We should know better. But masculinity serves as a way to continue to leave un-interrogated some of our assumptions.

In Adichie’s brief exchange, the interviewer set her question up in ways that seemed leading. In that context – when receiving a question that suggests transwomen always already enter feminist spaces through a history of male privilege – there is already little to salvage. I do think that language betrays us, and sometimes we fail to see something, or act right then and there. Adichie could have restated the question, rethought her assumptions, critiqued the premise of the query. That she did not is precisely what we should be considering an opportunity rather than a chastising imperative to discipline her – or those who do not see things the way “we” do. As it turns out, she continues to defend this narrative over and again. A cisgender-driven feminist thought that is perhaps engrained in Adichie should not result in judgment, but the starting point of action and conversation, en route to coalitional work. We must challenge these tired old arguments with counter arguments. Some of us do it from an academic platform, though that is not the only (or even main or “best”) way to do so. In my own research on masculinity and transmen, it was clear how, as one interviewee noted, “I had no past as a man, but I had no future (as a woman).” Others noted how, even as they faced life as men in the world, and seemed to benefit from male privilege, a sudden bodily exposure—be it a car accident, a medical test at an OBGYN office, or in potential erotic/sexual encounters—immediately removed this so-called privilege. Yes – Adichie, and others, should not fall on the “male privilege” trap. But we can explain, and elaborate on, why these are fallacies that need rethinking.

Sociologists too have lived with a fascination with gender deviance, understanding social norms through categorical gender lenses, and using excess to illustrate the rules of its ordering. (Perhaps as sociologists we need to challenge our simplest use of socialization altogether.) Privilege and power do not operate in simple binaries and opposites—we do know this from feminist thought—but to name biological circumstances (XY or XX chromosomes, external genitalia) as social is to reinstate sex circumstances as gender fixed criteria in our histories (with no room for variation or degrees). The humanities and social sciences of our times should move beyond the notion that transwomen are biologically male, and trans* activists are pushing us to see how damaging this is (and doing so through coalitional efforts). Thankfully, yet painfully, through her comments on being policed because of her femininity, Laverne Cox is really moving forward the discussion Adichie began. Cox did so by invoking a simple element: that her perceived deficit in the accomplishment of masculinity was indeed the fact of her femaleness (not just her femininity) and an “unknown” (if not unspoken) gender identity. That uncovers a previous social scientific approach to difference that challenged, and simultaneously reified, sex/gender.

We must challenge feminism in transformative ways, so that transwomen’s womanhood is no longer addressed through discourses of male privilege. However, that does not require forcing cisgender feminists to equate transwomen’s experiences with cisgender women’s experiences. What is damaging is not just the erasure of trans experience and identities as women, if they so wish to see themselves as (some trans* people do not abide nor work within that binary), but the homogeneous articulation of a single womanhood, which feminist thought has constantly refuted. To say ‘trans women are trans women’ is noting women with a particular life experience, and that can be, without the automatic mainstream-feminist compulsory answer that falls back on the tired “male privilege” narrative. In thinking intersectionally, one should be disturbed not so much because of the separate articulation of transwomen from (but also as) women; but the overgeneralization of that statement and what it erases – Jenner, Cox, Mock, Gutiérrez, and others have infinitely distinct experiences based on class and immigration and race and ethnicity and education and age and body type/size and ability, to name but a few markers.

Because of Adichie’s intent to see transwomen as non-universally women, I still believe Adichie’s feminism is intersectional. It may not be my cup of tea, and yes, I will continue to resist that narrative. But that should not reduce her history of intersectional work to ashes because of a single criticism. We must also be critical of the uses and abuses of the terms and their reach—here, I am reminded of the impossibility of intersectionality in Jane Ward’s Respectably Queer (in this case, in three sites that used sexuality as the basic premise to show the ways in which race/class/gender could not be addressed in tandem). And I see a chance, an opportunity, to build, not to shut down. What remains for us is the harder work of communicating across differences, which is not so shallow. It requires commitment, but also, an understanding of these feminist postures. Yet, I agree, it certainly does not require their endorsement.

I am not suggesting that we should not hold our activists, scholars, heroines or public intellectuals to task – not at all. What I am suggesting is that we do not disavow them because they’ve taken a historically narrow position, given their own social location and experience. What I am suggesting is that we take a stand (especially those of us, non-trans scholars) to challenge, as in my opening vignette, both the assumptions about second wave feminism as the uncritical read of trans* lived experience. Laverne Cox’s tweets (which can be read in their totality here) were filled with an intent to engage, to communicate and challenge, and to not alienate Adichie as a feminist cisgender woman – and by extent, feminist cisgender women. I sure hope those of us, trans* and not trans-identified alike, can at least follow in Cox’s footsteps.

_____________________

Salvador Vidal-Ortiz (Ph.D.) is associate professor in the sociology department at American University (AU), in Washington, DC. He coedited The Sexuality of Migration: Border Crossings and Mexican Immigrant Men (NYU Press, 2009) and Queer Brown Voices: Personal Narratives of Latina/o LGBT Activism (University of Texas Press, 2015). Aside from his Fulbright-based research on forced migration/internal displacement and LGBT Colombians, he is now engaged in a new project, with Juliana Martínez, also from AU, on “Transgendering Human Rights: Lessons from Latin America.” He was an inaugural editorial board member of Duke’s newest journal TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly.

Salvador Vidal-Ortiz (Ph.D.) is associate professor in the sociology department at American University (AU), in Washington, DC. He coedited The Sexuality of Migration: Border Crossings and Mexican Immigrant Men (NYU Press, 2009) and Queer Brown Voices: Personal Narratives of Latina/o LGBT Activism (University of Texas Press, 2015). Aside from his Fulbright-based research on forced migration/internal displacement and LGBT Colombians, he is now engaged in a new project, with Juliana Martínez, also from AU, on “Transgendering Human Rights: Lessons from Latin America.” He was an inaugural editorial board member of Duke’s newest journal TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly.

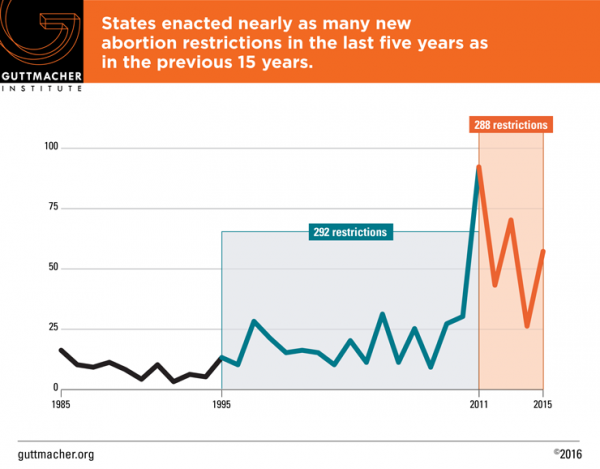

With a 5-3 vote, SCOTUS ruled that H.B.2 created an undue burden for the women of Texas. And the female justices played a

With a 5-3 vote, SCOTUS ruled that H.B.2 created an undue burden for the women of Texas. And the female justices played a  Ashley Brant, DO, MPH is an obstetrician-gynecologist and abortion provider. She completed her residency at Baystate Medical Center in western Massachusetts. Her research focuses on contraceptive access and medical education. She currently practices in Washington, DC.

Ashley Brant, DO, MPH is an obstetrician-gynecologist and abortion provider. She completed her residency at Baystate Medical Center in western Massachusetts. Her research focuses on contraceptive access and medical education. She currently practices in Washington, DC. So, back to my first SWS winter meeting. It was amazing, of course. I felt like an academic celebrity, having many people – some whom I knew, many whom I did not – express their appreciation for my blog, Conditionally Accepted. Admittedly, with such visibility as an intellectual activist, there is a lingering twinge of the mentality I was forced to adopt in grad school: “what about my research?” I thought privately. Obviously, these colleagues care about my research, as well. But, I found that the meeting, unlike other conferences I’ve attended, was just as much about research as it was about feminism, activism, and building a community. At what other conference would I feel torn between attending a session on feminist public sociology (hosted by the fine folks at

So, back to my first SWS winter meeting. It was amazing, of course. I felt like an academic celebrity, having many people – some whom I knew, many whom I did not – express their appreciation for my blog, Conditionally Accepted. Admittedly, with such visibility as an intellectual activist, there is a lingering twinge of the mentality I was forced to adopt in grad school: “what about my research?” I thought privately. Obviously, these colleagues care about my research, as well. But, I found that the meeting, unlike other conferences I’ve attended, was just as much about research as it was about feminism, activism, and building a community. At what other conference would I feel torn between attending a session on feminist public sociology (hosted by the fine folks at  What I take from life’s lessons is that one can really benefit from looking just a little bit further to find what one needs. My program devalued research on my communities – Black and LGBTQ. But, had I attended just one SWS conference, I would have found that there exists an academic space where that work is valued without question. My program sought to “

What I take from life’s lessons is that one can really benefit from looking just a little bit further to find what one needs. My program devalued research on my communities – Black and LGBTQ. But, had I attended just one SWS conference, I would have found that there exists an academic space where that work is valued without question. My program sought to “ Eric Joy Denise is a Black queer feminist sociologist and intellectual activist, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Richmond. Their research focuses on the impact of prejudice and discrimination on the health, well-being, and worldviews of oppressed groups, especially those marginalized by multiple systems of oppression (e.g., LGBTQ people of color). They are the founder and editor of the blog,

Eric Joy Denise is a Black queer feminist sociologist and intellectual activist, and an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Richmond. Their research focuses on the impact of prejudice and discrimination on the health, well-being, and worldviews of oppressed groups, especially those marginalized by multiple systems of oppression (e.g., LGBTQ people of color). They are the founder and editor of the blog,  I hearken back to the consistent message I heard throughout my life from my political activist father – that we must stand up for our beliefs. In the 1940s and 1950s, he was a very effective union organizer, fighting for better wages and working conditions for working men and women. But in 1954, he was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) to answer the now-infamous question, “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party (CP) of the United States?” After much emotional wrangling, he decided to challenge the committee’s legality. As a result, he was “blacklisted” from employment in the U.S. and could only find work selling life insurance for 15 years through a Canadian firm. Again in 1965, he was subpoenaed to testify before the Committee. By that time, he had become a prolific playwright, writing about his experiences within the labor movement in an attempt to give voice to working people. His life choices affected his family. We lost friends and were rejected by family members. And yet I have internalized – without a doubt – the importance of challenging injustices.

I hearken back to the consistent message I heard throughout my life from my political activist father – that we must stand up for our beliefs. In the 1940s and 1950s, he was a very effective union organizer, fighting for better wages and working conditions for working men and women. But in 1954, he was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) to answer the now-infamous question, “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party (CP) of the United States?” After much emotional wrangling, he decided to challenge the committee’s legality. As a result, he was “blacklisted” from employment in the U.S. and could only find work selling life insurance for 15 years through a Canadian firm. Again in 1965, he was subpoenaed to testify before the Committee. By that time, he had become a prolific playwright, writing about his experiences within the labor movement in an attempt to give voice to working people. His life choices affected his family. We lost friends and were rejected by family members. And yet I have internalized – without a doubt – the importance of challenging injustices.

don’t feel constrained by their mission to help, but rather are moved to choose jobs based on their individual intellectual curiosities. I am confident that if giving back is in their heart, then they will find a way to help people by becoming social workers, teachers, attorneys, doctors, engineers, chemists, or graphic designers. So, my dear students, be selfish. And while you are at it, do your best in whatever field you choose. I’m sure you will positively impact a life or two or more along the way.

don’t feel constrained by their mission to help, but rather are moved to choose jobs based on their individual intellectual curiosities. I am confident that if giving back is in their heart, then they will find a way to help people by becoming social workers, teachers, attorneys, doctors, engineers, chemists, or graphic designers. So, my dear students, be selfish. And while you are at it, do your best in whatever field you choose. I’m sure you will positively impact a life or two or more along the way.