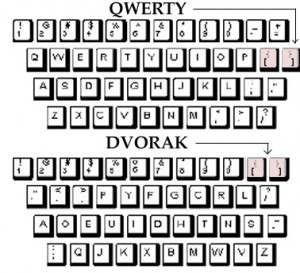

Sometimes the best products and business models don’t “win” in the market, while lesser products and plans triumph. Cases in point: the dominance of the QWERTY keyboard over better designs (like the Dvorak), and—in the days of Ye Olde Visual Media—the way the VHS standard consigned BetaMax, with its superior picture quality, to the dustbin of history.

Economists have long puzzled over these failures and have advanced a number of explanations, including the compelling theories of Brian Arthur, whose work on increasing returns and market “lock-in” was instrumental in the US government’s anti-trust case against Microsoft. As Arthur has shown, merely having a head start in terms of market share can allow an inferior product to continue growing that share until it dominates the market, shutting out any competition.

But these cases also showcase the value that economic sociology can add to our understanding of markets, particularly through the lens of culture—the sort of variable that gets thrown into the dreaded black box of “preferences” in economic models. Black boxes exist in the world of academic theory to contain factors that are unknown, perhaps unknowable; this often gets interpreted to mean that the factors are not worth knowing about. Thus, the origins of preferences, and the ways preferences change, are treated by most economists as uninteresting and irrelevant.

Yet for sociologists, these are the most interesting things about economic behavior. Culture, class, identity and ideology—core issues in sociological research—all play a role in shaping preferences. These forces are not easy to model, which is a major reason they get left out of economic scholarship, where elegance and parsimony are valued above empirical verisimilitude. So, as one classic article put it, sociologists get “dirty hands” from dealing with lots of data and variables, while economists construct “clean models” that exclude such messy complexities.

What sociological theories may lack in “cleanliness,” however, they make up for in explanatory power. I was struck by this recently while contemplating a puzzling business failure in my own backyard: the Belgian supermarket chain Delhaize shut its doors in Cologne and Aachen, the two cities where the firm had tried to gain a foothold in Germany. Here were stores vastly superior to their competition—selling a much broader and higher-quality range of goods than anything available in local grocery chains, all at very reasonable prices—and yet the business failed.

Adding to the mystery, Delhaize had long ago proved that their business model transplanted well to other cultures by launching the chain to great success in Asia and the US. Yet they couldn’t make a go of it just across the border from the firm’s headquarters. High quality, competitive pricing and good locations weren’t enough to make the model work in Germany.

The loss was keenly felt in the expat community here in Cologne. People don’t usually get sentimental about grocery stores, but Delhaize inspired extraordinary loyalty and appreciation among people who cared about good food. If you come from a place where a wide variety of fresh, high-quality, attractive foods–particularly fruits and vegetables–are readily available, then it’s a huge shock to walk the aisles of a German grocery store. The baked goods—bread and pastries—are terrific, and justly celebrated. But the produce and meats are really dismal, even in specialty shops, and the supermarkets are quite depressing. I come from the US, but I’ve heard the same refrain from friends and colleagues who hail from Turkey, France and Thailand.

All of us were struck to find, here in the wealthiest country in Europe, that the fruits and vegetables often look quite bedraggled, as do the meat and fish selections. Even the very expensive places tend to have the kind of quality that you would expect at a Stop-n-Shop in the US, and the selection is both unreliable and extremely limited. Some days you’ll find cucumbers, some days there will be none. There will always be apples, but at most two or three kinds instead of the six to 10 varieties you typically find in a big-city American grocery store. I have never seen a salad bar here, although I’ve offered a €100 bounty for the past three years to anyone who can show me one in a German grocery. You can compensate somewhat by going to a different specialty store for each class of food you want—fruits, meats, etc.—but the quality and reliability of the selection still isn’t very good. And few people have time to schlep to a half dozen different stores to buy their food.

These are not life-and-death issues, but they make a big difference in one’s ability to plan meals, follow recipes, or just enjoy favorite foods. When I asked German sociologist colleagues about this, I was surprised to find that they knew exactly what I was talking about: they acknowledged the poor quality of the produce and meats in German grocery stores, and blamed it on the carry-over of a wartime mentality. That is, the older generation in Germany—the parents of people in their 40s and 50s—grew up with rations and privation, and a mindset that meant eating was about survival, not enjoyment. They fed their kids for quantity of calories, not quality, creating tastes, expectations and norms that have persisted into the present day.

Tastes, expectations, norms? If you join economic sociologists in unpacking the black box of preferences, these are exactly the sorts of things you find. Clusters of these factors become the most powerful explanatory variables in sociology, like identity and culture.

How does this help us understand the Delhaize closures in Germany—and even predict such events in future? For me, the “missing link” cropped up in a presentation by Professor Sophie Quellier of Sciences Po, who gave a talk last summer at SASE (the Society for the Advancement of Socio-Economics) on the market for peaches in Paris. She made a compelling case that consumers don’t automatically choose the highest-quality goods, but must be taught to recognize them, value them, and most importantly, buy them.

If this sounds similar to the argument about cultural products in Distinction, it is: Quellier’s thesis could be described as “Bourdieu goes grocery shopping.” For those not familiar with Bourdieu’s magnum opus, the great French sociologist used consumer survey data to show how class distinctions are reproduced through matters of taste. He finds that seemingly personal preferences—such as aesthetic choices in furniture, clothing or art—are actually learned social behaviors. Moreover, those choices have little connection to sensory experiences (such as pleasure) but rather serve to distinguish members of different classes from one another, rendering visible the structure of social hierarchy.

Quellier’s work follows the process of “educating” consumers to prefer a fine peach over less-flavorful and less-expensive varieties. It requires a sustained, intense effort, involving everything from advertisements to public taste tests, à la the “Pepsi Challenge.” To see how this works, check out this ancient Pepsi Challenge ad (with Welcome Back Kotter‘s Gabe Kaplan, of all people), which seeks to change consumer preferences with a variety of rhetorical strategies, including both conformity pressure (“Nationwide, more people prefer the taste of Pepsi to Coca Cola”–join the group!) and appeals to individuality (“Let your taste decide”–don’t follow the Coke-drinking herd!).

This series of television spots, along with print ads and in-store tastings—a veritable marketing juggernaut that carried on for years during the 1970s and 1980s—never succeeded in dislodging Coke from its position as the number one soft drink in America. Even if Pepsi was the superior product, by virtue of being chosen as “best-tasting” by the majority of test participants, it couldn’t make much of a dent in consumer preferences.

As a recent series of MRI studies showed when replicating the Pepsi Challenge, drinking Pepsi activates a part of the brain connected to the physical sensation of taste, while Coke activates a part of the brain connected with feelings about identity. Remarkably, beliefs and ideas win out over embodied sensory experience.

Which goes a long way toward explaining the Delhaize failure in Germany. Quellier’s work, combined with “neuro-marketing” research, suggest two conclusions that are particularly relevant to this empirical case:

- preferences connected with food consumption are deeply-rooted and slow to change (unlike say, preferences for fashions in clothing or technology)

- any effort to change food-related consumer preferences have to contend more with ideas than sensory experience—eating and drinking have more to do with the sense of self than the sense of taste

In a culture where food traditions, family culture and national history come together in a cuisine of bland flavors, fried meats and few fresh fruits and vegetables, Delhaize had little chance of succeeding. If it had put in the kind of cultural reprogramming effort described by Quellier, Delhaize might have been able to carve out a stable niche in Germany. Would it have been worth it economically? Hard to say. But without such an effort, the chain was doomed.

This also implies something about Delhaize’s successes internationally: the extent to which the chain has thrived outside of Belgium may have less to do with the quality of their products than the cultural fit between the values and preferences Delhaize represents (e.g., high quality and broad selection are important) and those of the countries where it has launched its stores. This foregrounds the role of culture in business, in everything from international expansion to mergers and acquisitions, and the value of sociological accounts in clarifying how culture works. One wonders what would happen if more business leaders had backgrounds in sociology rather than finance.

Comments 22

Phil — May 20, 2010

I also felt the loss dearly when Delhaize shut its doors. I had been trying to convince friends (some of whom lived only a block away) to check out the place - to no avail.

Have you noticed that Germany has no "foreign" supermarkets whatsoever? Even Wal-Mart failed. No idea why this is so. I don't think Germans want to "buy German" necessarily (see all the flourishing little foreign grocers, and most products are made elsewhere) but they seem to like their BRANDS to be German. Here's a theory: Maybe it has to do partly with modern German nationalism which, at least until recently, has been mostly economic. You'll rarely find a German (openly) proud of German history... but they'll grin proudly when associated abroad with Mercedes or Siemens.

Christian — May 20, 2010

That is actually an interesting observation. But the question is if the failure of Delhaize is only because of the German "Hausmannskost" society that cannot be convinced by quality food or if, as Phil put it, brands are our new national pride (even so while ALDI lost its image as a poor-people-store I don’t know if the majority of Germans would be delighted if you associate them with ALDI). Maybe another development is interesting in this case: Not only foreign grocers fail, but so do national once. I remember a couple of years back you had a variety of different grocery stores from Extra over Plus to Real. While they still exist, the grocery landscape is even more dominated by ALDI, Lidl and Kaufland today. So maybe this is a classic economic case of an oligopoly with too dominate market actors. But I have to admit that even that does not excuse the obvious lack of appreciation for good food in this country.

Christian — May 25, 2010

Dear Brooke,

"Hausmannskost" is just a colloquial term for the German 'Eau de cuisine'. The classic Bratwurst, Schnitzel, mashed potato and different kind of Kraut combo that will be served in most restaurants.

Best

Christian

Jeff — May 25, 2010

Another brilliant piece Brooke! But does Bourdieu really argue that "choices have little connection to sensory experiences (such as pleasure) but rather serve to distinguish members of different classes from one another"? Couldn't one argue that taste functions as a device for legitimating class differentials precisely because it is so deeply embodied as a sensory experience...essentially transforming arbitrary social inequalities into bodily sensations of "yummy" versus "ick" that just feel so natural?

Speaking of Gabe Kaplan, have you ever seen his awesome "Battle of the Network Stars" triumph? I'm not the only one to consider it the best youtube clip ever:

http://sports.espn.go.com/espnmag/story?id=3712343

Hondo — June 1, 2010

Brooke, try tying this observation back to Pop Finance. Do investors make suboptimal investment choices based on cultural and social norms even when all objective evidence points to better choices? I submit the answer is yes: look at people whose "investment strategy" is a lottery ticket or a trip to the penny slots.

As U of Chicago's Mortimer Adler described in "Six Great Ideas," there are matters of taste and matters of truth. Perhaps it is no surprise that in matters of taste, there is no accounting for taste! Older Germans may prefer flavorless food, just as underperforming investment clubs prefer high-risk, low-expected value stocks.

Phil — June 2, 2010

In response to Jeff's question of >>does Bourdieu really argue that “choices have little connection to sensory experiences<>They basically looked at the offerings from Delhaize and said “Meh. No thanks. We like our flavorless, dismal-looking fruits and vegetables better.”<< is slightly off the mark. In fact, Brooke says it herself, when she says most people stuck with Coke after the Pepsi challenge. The point is, it wouldn't have mattered which apples Delhaize put on offer, in fact, Delhaize might have been better off offering worse-looking food! For the sake of tangible explanation, and in defense of Delhaize, I'll posit two explanatory factors:

(1) Germans really do like their fruits and veg mangy. I know, it's weird. But you should look at what the bourgeois avantgarde buys at "bio" (organic) supermarkets, at double or triple the price. It's dented, tiny, misshaped morsels of nature they demand most. Many Germans don't trust any food that looks too good (just like the French don't trust a car without dents); the Germans prefer to wash the soil off their carrots themselves (in fact, there might be a factory *adding* soil to produce somewhere in Germany); and if their apple has some bruises, hey, at least it wasn't sprayed and waxed. My guess is this has something to do with the specifically German 1968 reolt descent into environmentalism. Because that age and former scene is by now the social elite, their purchase of back-to-nature, organic, blemished foods is setting the standard for others social groups to follow.

(2) I stick by my (subconscious) nationalism argument, which says that Delhaize was destined to fail. Most people, if they ever even entered a Delhaize outlet, had made their mind up to be skeptical of what was on offer. Don't get me wrong, I think a world without any nationalism whatsoever (except for the self-ironic) would be the best world. But many Germans have quite few socially sanctioned ways of expressing their national sentiment, so they identify privately with brands and other institutions perceived to be undeniably but inoffensively "German". If Delhaize had bought up a faltering local supermarket chain, kept that brand, and pumped the shops full of better-quality products, it might have been a success story. Back in the days when Delhaize was still open, I would often show up to parties with Belgian beer; stronger, cheaper, and differently tasty from German beer. Many friends would politely drink a bottle, note that it didn't conform to the "Reinheitsgebot" of 1516 AD (beer purity law, the oldest, and probably only never-broken law in the country), and leave the rest to be drunk be me (with great pleasure).

Of course these factors are on-average and ceteris-paribus!

Two final footnotes:

* The taste of food gets better the further south you get in Germany. I don't know about fresh produce, but definitely Bavaria and BW have a good enough reputation for cooked food, and Cologne has one of the worst in the country. So Delhaize might have entered the market at the wrong place.

* I'll collect that 100$ reward, thank you. I do know of *one* (yes, a single one) supermarket in Frankfurt with a salad bar. I assume an ICE ticket is a reasonable price to pay for a self-styled salad lunch??

Brooke — June 2, 2010

Dear Phil,

Brilliant! I wish I had thought to ask you earlier about Germans and food, because you have explained a lot. Three things really got my attention:

1. "It's dented, tiny, misshaped morsels of nature they demand most. Many Germans don't trust any food that looks too good "

Oh! I was wondering why the highest-priced produce often looked the worst.

2. "Back in the days when Delhaize was still open, I would often show up to parties with Belgian beer; stronger, cheaper, and differently tasty from German beer. Many friends would politely drink a bottle, note that it didn't conform to the "Reinheitsgebot" of 1516 AD (beer purity law, the oldest, and probably only never-broken law in the country), and leave the rest to be drunk be me (with great pleasure)."

That is the Pepsi Challenge of beers. It also reminds of that scene in "Amadeus" where the Emperor Joseph II rejects one of Mozart's compositions because it has "too many notes."

3. "Bavaria and BW have a good enough reputation for cooked food, and Cologne has one of the worst in the country."

That explains "Himmel und Aad," Cologne's much-vaunted blood sausage delicacy. *Shudder.*

As for the salad bar, I'm dying to know: which grocery store has it? Is it a chain? Do the greens have that mangled and brown look so important for bourgeois cred?

Best,

Brooke

Steve Dix — June 3, 2010

Rewe used to do salad bars. There was a serve-yourself one in the one in Bismarckstr / Venloerstr when I worked in Belgischer Viertel. That's nearly 10 years ago though.

Culture et origine des préférences « Rationalité Limitée — June 10, 2010

[...] intéressant billet sur le blog Economic Sociology à propos de la manière dont la culture peut structurer les [...]

Fabian | The Friendly Anarchist — June 14, 2010

Very, very interesting and a pity reading about Delhaize having shut down. I frequently went there to shop for food and Belgian beer, too, when I still was living in Cologne. (Oh, and I’m a German… I still love Belgian beer! :)

"They basically looked at the offerings from Delhaize and said “Meh. No thanks. We like our flavorless, dismal-looking fruits and vegetables better.”"

This is probably a bit silly. What puzzles me is that nobody already wrote that Germans are CHEAP when it comes to food. Very, very, very cheap indeed. For me, this is the number one reason I can find why the supermarkets offer so little variety and so low quality. The same is true for restaurants: Germans go where it's cheap, even if the quality is bad. OR they might choose a stylish place to prove they are "in style". Quality comes always last, that's for sure. Most Germans still prefer spending their money on cars and cameras. Delhaize had a more expensive look, and thus suffered, as probably even the Rewe stores might. If it's not a "discounter", most people aren’t interested.

Concerning the other arguments raised: The nationalistic one just doesn’t convince me. I honestly don’t think this is an issue, as the later post-war generation actually often avoids cooking typical German food and is proud to "know about" Italian pasta, coffee and wine. (Even if they actually don’t.)

The "looks" argument is important, I think: Too beautiful apples raise suspicion - and, I think, at least in part rightly so. The thing of course is this: Instead of really getting better apples (to stay with the example) from your own tree, Germans will buy the ugly stuff Aldi offers them, thinking that they are "better" than the waxed ones you like to eat in the US.

Oh, and a CHEAP (!) salad bar can be found at uni mensa. ;)

I think there also used to be one at the Rewe in Dürener Straße, but I’m not sure if it still exists.

Thanks for this interesting article.

Culture and Consumption, Part II: The Mystery That Is Tchibo » Economic Sociology — June 18, 2010

[...] usually unquestioned, is that these results are applicable everywhere. But the case of Tchibo, like the failure of Delhaize, presents some compelling empirical reasons to doubt the generalizability of marketing and strategy [...]

Market Failures and Inefficiencies, Culture and Control | The Global Sociology Blog — July 11, 2010

[...] on this topic.Powered by Greet BoxA while back, Brooke Harrington, over at Economic Sociology, posted on how the best products do not always prevail on markets, using as example the Qwerty keyboard. It [...]

wsteffie — August 2, 2010

I have to agree with Phil here, we really do like our fruits and veggies mangy.:-) That is of course because we have been told by the media for years that "Bio"/"Organic" (free of pesticides & gene manipulation) is what quality is all about in terms of fruits and veggies.

I'm not familiar with Delhaize, so I cannot comment on that, but have to say that Lidl is successful over here even though they are from Austria.

Germans do love American products. Whenever the local discounters (Aldi, Penny &lidl) have their American week, people shop like crazy, thinking that the products are actually American products. A little red, white & blue on the label will go a long way over here.

Phil — September 20, 2010

Living in the USA at the moment, I must say: I miss the old German tiny dented fruits and veggies! Not because of their dentedness and punyness but because I loathe spending 5 Bucks for three large beautiful shiny bell peppers (too much money, whatever size!), only to find out at home that they're moldy on the inside. (my experience from last week - wtf?) I'm also seeing and enjoying the cheap jeans and shoes thing on the other hand. Maybe there IS some economic-structural aspect to this after all? Some good'ole terms-of-trade kinda thing, maybe?

Not that its my back-to-my-economics-roots day; but evidently every consumer durable from China (durable if you consider 1 year a long time) is dirt-cheap in the US, while the well-protected US farm products keep poor families on Doritos and high fructose corn syrup products. I think the brute (political) economics do matter in this story at as much as the social-perception/bizzarre-preferences aspect.

(Three cheers - red, yellow and green - for small and unspectacular Dutch and Israeli capsicii!)

Jens M. Wiig — January 26, 2011

This is a bit funny: I was seaching on Google " Food from DelHaize makes me flatulent", and I ended up on this website! Very intersting site, but of course, it does not answer my question.

Being a Norwegian living in Belgium, I did not know about the German failure of DelHaize, but maybe more peolpe in Germany had the same problem with the DelHaize food (especially their meat produckts)as I do?