Would you buy contact lenses from a coffee shop? How about a new car? Perhaps some insurance products with your drink?

If you live in North America, these questions probably sound absurd. But it’s the business model of Tchibo—a firm which describes itself in utter seriousness as “Coffee shops also selling housewares, accessories, and clothes.” In practice, this model is even more confusing than it sounds, because—as the official corporate slogan puts it—Tchibo is “A New Experience Every Week.” So, as of June 18th, they’re selling household furniture; a few months ago, it was American country-western clothing (yup, they’ve got both kinds). Next month, who knows?

The Hamburg-based retailer starting selling coffee beans within Germany in 1949, expanding to what the firm coyly calls “non-food items” in 1973 by using their retail space to sell items placed there on consignment by other companies. The “extended product line” started with things that were at least thematically related to coffee and food consumption, like place mats and serving trays. But soon the model spun off into wild new directions, like cars and cowboy boots. And now Tchibo is not only Germany’s largest coffee shop chain, but has expanded into 10 other countries, from the UK to Turkey, with more to come.

Here’s the mystery: this isn’t supposed to work. In fact, what Tchibo does is supposed to be disastrous—diluting their brand and confusing customers (to say nothing of investors) with an ever-changing array of unrelated products unrelated to the coffee business. From a marketing and strategy perspective, the firm has committed the deadly sins of creating “brand complexity, clutter and confusion.”

This is supposed to cause consumers to stay away in droves. For example, researchers at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business have found that firms that span a variety of product categories experience “penalties for generalism” in the marketplace. Using data from eBay and the US film industry, sociologists Greta Hsu, Mike Hannan and Özgecan Koçak showed that firms like Tchibo are viewed as “difficult to interpret” in terms of market categories, resulting in consumers “avoiding interaction with the uninterpretable producer and devaluing its offerings” (2009: 167).

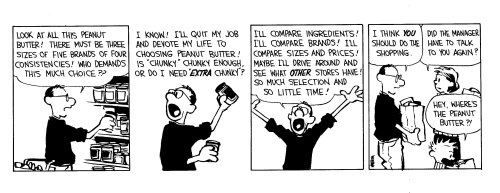

A lively experiment by social psychologists Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper (2000) suggests how this works at the cognitive level. Their study presented participants with free samples of several fruit jams, then measured how many subsequently bought a jar. The researchers varied the experimental conditions so that one group of participants selected from a set of six different flavors of jam (the “limited-choice” condition), while the other group sampled from a set of 24 flavors (the “extensive-choice” condition). While both groups tried just one or two flavors, their purchasing behavior varied by an order of magnitude: only 3% of those in the “extensive-choice” group bought a jar of jam, compared to 30% in the “limited-choice” group.

The researchers attribute this difference to “choice overload” among those faced with too many options: the purchase decision just requires too much cognitive processing, so the consumer opts out completely. Thus, the state of the art thinking in marketing and strategy research is “keep it simple.” And there’s more than just experimental data to back that up: when consumer products giant Proctor & Gamble shrunk the range of their “Head and Shoulders” product line from 31 versions to 15, hair care sales per item more than doubled.

And yet…Tchibo thrives despite its unpredictable and often chaotic-seeming array of product offerings. So far, the firm thrives only in Europe. And that may be a big clue to the mystery.

All the research cited in this post is based on studies conducted in North America.The assumption, usually unquestioned, is that these results are applicable everywhere. But the case of Tchibo, like the failure of Delhaize, presents some compelling empirical reasons to doubt the generalizability of marketing and strategy research, much of which comes out of universities in the US.

Is Germany just a special case of cultural misfit between research findings and consumer behavior? Or is the problem more widespread? Perhaps Tchibo will expand to the US and give us a chance to find out.

Comments 7

Martin — June 20, 2010

I do not think the reasoning on brand complexity applies to Tchibo, because they do not try to establish themselves as a brand for housewares, accessories, clothes etc. Their brand identity is more comparable to a retail chain with a certain assortment (coffee and cheap/useful/decorative things) and a common store design. They also eliminate the "choice overload" by only offering one item of a kind per week (e.g. one week they might offer a knive set, but only one and never two different ones to choose from).

And related to this: their success could be a result of the weekly changing products. Everytime you see an interesting item you know it is offered only for a short time -- this requires a quick buying decision without the ability to compare products and prices.

Phil — June 21, 2010

The running joke in my family goes: "Rumour has it, some Tchibo stores still sell coffee."

Özgecan — June 24, 2010

[Warning: This comment will partly be a repetition of Martin's comment because I wrote it as an e-mail first, without having seen his comment. I'm glad we agree though.]

I was, for a while, puzzled about Tchibo as well. But after having shopped

there, I am not: the humidifier I bought broke down in one day. I still

visit the store once in a while to look around, but after that experience

I have only bought a little trinket for my daughter. I would not buy any

kind of good whose quality I care about at that store. I think the value

they provide for customers is that they decrease search or 'discovery'

costs. Stepping into a store whose setting you are familiar with, you

explore different categories of goods in a safe environment. You step into

the store not knowing that you need a humidifier, you see it there, you

discover that you may in fact need a humidifier, it appears cheap enough

to give it a try, and you buy it. It's a low cost store, but unlike

Wal-mart or similar stores, there are very few alternatives. You get to

learn about a category with few alternatives in that category.

In Turkey, Tchibos appear to be very popular. I would guess that a big

attraction is that most goods appear to be of German origin. It's sort of

like a foreign Sears or Lands End seasonal catalogue (both nonexistent in

Turkey but known to customers who have lived abroad) materializes in the form of a store. So it's not only that you are

discovering a new category of goods, but also a category of goods that

originates in a desirable Western culture. About your conjecture at the

end of your blog: I don't think they'd be as successful in the US, where

the novelty appeal would be considerably less, and where search/discovery

costs are much lower than in Turkey.

So my prediction is that Tchibo will not last long, that it is filling a

gap that will close as information and goods travel more freely. I would

also predict that customers looking for higher quality products will

abandon it much sooner, or shop much less and do what I'm doing: use the

changing store displays to gather information about the category but go

buy the products elsewhere.

A more surprising thing I've encountered is Tchibo branded products being

sold at Migros (supermarket chain, sort of like Safeway). That, I predict will not last long at all.

That said, I would like to point out that I am not necessarily going to

argue that everything will eventually be consistent with the theory as it

is. In fact, there is recent research being done by Mike Hannan and his

students that shows that some groups of consumers may in fact prefer

generalists. Kovacs and Hannan (forthcoming in RSO) find that activist

reviewers of food service organizations are less bound by category

conventions. Pontikes (2009) finds that venture capitalists prefer

category-spanning start-ups while customers don't. So perhaps expert

audiences prefer generalists. (This does not help Tchibo though.)

In relation to this, I think you indirectly raise an important question:

specialism/ generalism on the basis of which categories? I saw a store in

an airport that only sold striped things. They sold infant clothing,

purses for ladies, notebooks, and many other goods in different

categories. But they were all striped. You could say they specialize in

things striped, but could you be an expert in stripes? I don't see

how that could be a competitive advantage.

Also: I don't agree with you that Iyengar and Lepper's work shows how

'categorical imperative' works at the cognitive level. They show that

people cannot cognitively process too many alternatives and end up

deciding not to choose. (I love the Calvin and Hobbes strip on this, I had

not seen that one.)

In the categorical imperative story, producers/sellers that offer products

in different categories are penalized because their identities are

considered impure (this is true especially in market categories where

authentic identities are an attraction for customers), or because

customers or intermediaries do not know how to classify and therefore

evaluate the producers (this is the main story in Ezra's seminal 1999

categorical imperative paper), or because producers operating in multiple

categories cannot serve the customers in each of the categories as well as

the focused producers in those categories (and therefore are competed out

of those categories). The customer perception part of this story

(inability to classify and therefore benchmark and evaluate) is the most

similar part to Sheena's story, but still it is quite different: the

confusion arises not because there are too many alternatives in the same

category but because the same producer operates in too many categories. So

an analogy would be: you would prefer Wilkin & Sons brand jams to Heinz

brand jams because you know Heinz as a ketchup producer.

This is not to say that the two theories are completely unrelated:

categories exist / are created to make choice easier. I'd predict that if

those jams were organized in a way that customers could categorize them

(e.g. sweet ones to one side, sourish ones to another), more jams would be

sold.

Özgecan

wsteffie — August 2, 2010

Brand complexity works well over here in Germany, which is not only evident with Tchibo, but also with our discounters (Aldi, Penny &Lidl). The discounters have been offering different products once a week for years and Tchibo just followed into their footsteps.

The Iyengar & Lepper experiment dealt only with jam and the Head & Shoulders example dealt only with shampoo (one product), that's not very complex in terms of brands.

I think complexity is the key since there are several different offers each week.

Lacin Tutalar — September 18, 2010

Your article on Tchibo makes me think that the picture looks very different locally. Thinking of Tchibo stores in Ankara, Turkey, the kind of complexity that will benefit Tchibo is the kind you mentioned in Culture and Consumption, Part I: Or, Bourdieu Goes Shopping. When I step in Tchibo stores in shopping malls in Ankara - and there are a few ones as street stores) there is something beyond popularity. I see items unsold, sometimes broken, sometimes in a total mass -like in bazaars that sell cheap imitation bags, watches, shoes, clothing, kitchenware. But when I click on the internet store on Tchibo, that week's specialty - that simple bathroom cabinet- can be already sold out!

So, stores like Tchibo seem to be clever on two things: First, open a store in a madly globalizing city whose people (their professional bodies and their old ladies) are hungry for distinction a la Bourdieu. Second, know that your store will have a double characteristic thanks to internet shopping. That means there may be two different customer profiles. The old lady likes to act like she is in a bazaar and likes to learn new things (but step by step). Add to this the image of Tchibo in a city that does not have a place like Ikea (yes, I wonder what will happen when Ikea opens in Ankara). A little complexity will lift her spirits up, but too much complexity can bore her. Then, the other type of customer -internet friendly- likes to take it cheap but also likes to take it before anybody else. Again, add to this the old ladies I increasingly see in mall corridors and in stores like Tchibo and their reaction to coffee, which is the smell of Tchibo-. The old lady may not prefer another coffee shop/chain like Starbucks because she finds it a little too intrusive to her localness, but Tchibo can seem harmless in that matter because it decorates your home, which has always been one of the priorities in Turkish case. So, Tchibo can already have the advantage in the store and extends it online for other younger generation. The question of quality is not the first thing here, and I doubt it'll ever be (for a considerable amount of buyers). Because quality is not always the first thing for neither those professional bodies nor old ladies and their husbands nor the young and the curious. Distinction and cheapness beats smell and taste.

Well, your wonderful article made me a chatterbox. Sorry and thanks :)