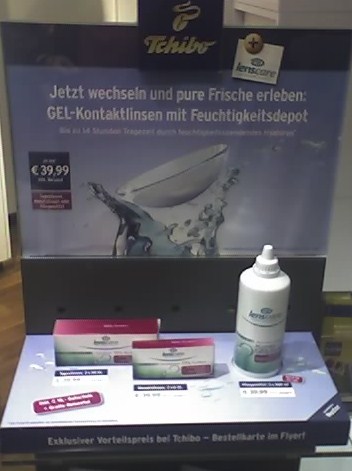

Would you buy contact lenses from a coffee shop? How about a new car? Perhaps some insurance products with your drink?

If you live in North America, these questions probably sound absurd. But it’s the business model of Tchibo—a firm which describes itself in utter seriousness as “Coffee shops also selling housewares, accessories, and clothes.” In practice, this model is even more confusing than it sounds, because—as the official corporate slogan puts it—Tchibo is “A New Experience Every Week.” So, as of June 18th, they’re selling household furniture; a few months ago, it was American country-western clothing (yup, they’ve got both kinds). Next month, who knows?

The Hamburg-based retailer starting selling coffee beans within Germany in 1949, expanding to what the firm coyly calls “non-food items” in 1973 by using their retail space to sell items placed there on consignment by other companies. The “extended product line” started with things that were at least thematically related to coffee and food consumption, like place mats and serving trays. But soon the model spun off into wild new directions, like cars and cowboy boots. And now Tchibo is not only Germany’s largest coffee shop chain, but has expanded into 10 other countries, from the UK to Turkey, with more to come.

Here’s the mystery: this isn’t supposed to work. In fact, what Tchibo does is supposed to be disastrous—diluting their brand and confusing customers (to say nothing of investors) with an ever-changing array of unrelated products unrelated to the coffee business. From a marketing and strategy perspective, the firm has committed the deadly sins of creating “brand complexity, clutter and confusion.”

This is supposed to cause consumers to stay away in droves. For example, researchers at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business have found that firms that span a variety of product categories experience “penalties for generalism” in the marketplace. Using data from eBay and the US film industry, sociologists Greta Hsu, Mike Hannan and Özgecan Koçak showed that firms like Tchibo are viewed as “difficult to interpret” in terms of market categories, resulting in consumers “avoiding interaction with the uninterpretable producer and devaluing its offerings” (2009: 167).

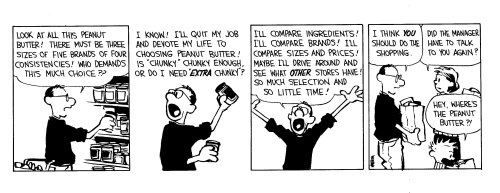

A lively experiment by social psychologists Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper (2000) suggests how this works at the cognitive level. Their study presented participants with free samples of several fruit jams, then measured how many subsequently bought a jar. The researchers varied the experimental conditions so that one group of participants selected from a set of six different flavors of jam (the “limited-choice” condition), while the other group sampled from a set of 24 flavors (the “extensive-choice” condition). While both groups tried just one or two flavors, their purchasing behavior varied by an order of magnitude: only 3% of those in the “extensive-choice” group bought a jar of jam, compared to 30% in the “limited-choice” group.

The researchers attribute this difference to “choice overload” among those faced with too many options: the purchase decision just requires too much cognitive processing, so the consumer opts out completely. Thus, the state of the art thinking in marketing and strategy research is “keep it simple.” And there’s more than just experimental data to back that up: when consumer products giant Proctor & Gamble shrunk the range of their “Head and Shoulders” product line from 31 versions to 15, hair care sales per item more than doubled.

And yet…Tchibo thrives despite its unpredictable and often chaotic-seeming array of product offerings. So far, the firm thrives only in Europe. And that may be a big clue to the mystery.

All the research cited in this post is based on studies conducted in North America.The assumption, usually unquestioned, is that these results are applicable everywhere. But the case of Tchibo, like the failure of Delhaize, presents some compelling empirical reasons to doubt the generalizability of marketing and strategy research, much of which comes out of universities in the US.

Is Germany just a special case of cultural misfit between research findings and consumer behavior? Or is the problem more widespread? Perhaps Tchibo will expand to the US and give us a chance to find out.