“Quote of the Month Club” is a new feature, inspired by stuff I read, combined with my longstanding love of the Harry and David Fruit of the Month Club.

If you have any economic sociological quotes you’d like to propose for this feature, please fire away. I’m taking suggestions.

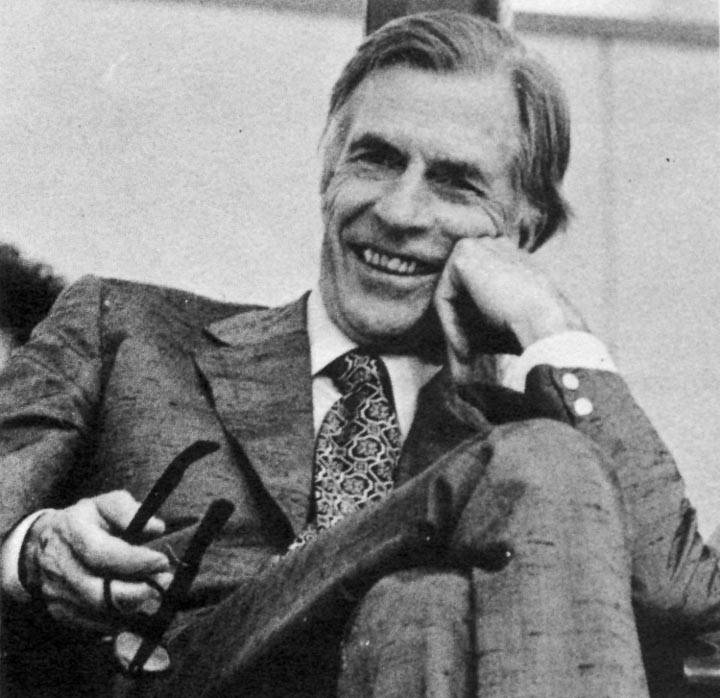

This month’s selection is from one of my favorite scholars of all time: John Kenneth Galbraith. I first became acquainted with his ideas at the age of 18, when I went to see a panel discussion between him and Noam Chomsky (what a lineup!). There was a reception afterwards, and I somehow worked up the courage to go ask him a question. He answered kindly, then reached down from his great grey eminence (6’9″) and patted me on the head.

Galbraith seemed like a lovely man, in person and in all the interviews I ever saw with him, and he was certainly one of the best writers ever to publish on money and markets–a Mark Twain of sorts for the social sciences.

He penned a number of pithy insider critiques of the economics profession. This is among the best, and it has a special poignancy as the US and other countries begin dissecting the causes of (and laying the blame for) the 2008 economic meltdown:

The experience of being disastrously wrong is salutary; no economist should be denied it, and not many are. –from Galbraith’s memoir, A Life in Our Times, 1982: 163.