Just after writing the post below about the ways the recent economic crisis may have shifted cultural attitudes toward consumption and frugality, I picked up Daniel Bell’s classic Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism and found this:

Just after writing the post below about the ways the recent economic crisis may have shifted cultural attitudes toward consumption and frugality, I picked up Daniel Bell’s classic Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism and found this:

“What we owe to the future is a capacity to produce.”*

This concern for the future, I think, underlies many of the behaviors we associate with the habits of people who lived through the Great Depression. The meaning of all that patching and mending, of raising chickens in the backyard and so forth, was not just to reduce consumption expenses, but to conserve the resources they did have for production–for future-building.

Of course, the ability to fix things and grow your own food are themselves types of productive capacity. In less complex societies, with less division of labor, survival depended upon those skills. One had to be able to provide for most, if not all, of one’s own needs independently, or within the household unit.

By the time my grandparents were born, that was no longer the case: for example, both my paternal grandparents grew up in the city of Chicago, and had to buy clothes and some of their food from stores, rather than making everything themselves. This isn’t a bad thing–just a modern thing. As Emile Durkheim–one of the founding fathers of sociology–famously argued, specialization and the social division of labor are necessary conditions for the material and intellectual development of societies. His point was that if everyone had to attend to their own survival needs, rather than paying someone else to provide them with food, clothing, and other necessities, it would be difficult for any one person to pursue certain valuable but time-intensive specialties, like scientific research.

My grandparents didn’t have the family wealth necessary to specialize that much: the Great Depression cut short their educations, so that my grandmother had to drop out of school at 15 to begin earning money as a maid for wealthier families, and my grandfather (who had hoped to become a lawyer) made it only part way through an associate’s degree program before his tuition money ran out and joined the Marine Corps.

While their individual trajectories were curtailed by the Great Depression, their frugal habits meant they accumulated a surprising amount of productive capacity at the family level of analysis. Specifically, they were able to save enough so that their first child, my father, could get a good education at a private Catholic school, and then become the first person in the family to earn a college degree. My grandparents themselves continued to live very modestly–in their 60s, they subsisted on Social Security and lived in a single-wide trailer in Florida mobile home park.

But because they were able to give my father the benefit of all the productive capacity they’d accumulated–their savings from blue-collar jobs, and all the methods they used to avoid spending money in other ways–he was able to make big leap in upward mobility. That future-oriented momentum made it possible for me to go even farther, so that the granddaughter of a woman who had to leave school in the 10th grade could graduate with a PhD from Harvard 70 years later. My grandmother died a few years before I graduated, but I think of her and my grandfather often, not only because I loved them but because I feel obliged to keep building on what they started.

That’s where the satisfaction of fixing things comes from: I’m not only remembering people I loved through imitation, but perpetuating their legacy by conserving productive capacity in many of the same ways they did.

Thus, what economist Robert Solow has written of the intergenerational transmission of wealth also holds for cultural and social capital:

“We have actually done quite well at the hands of our ancestors. Given how poor they were and how rich we are, they might properly have saved less and consumed more. No doubt they never expected the rise in income per head that has made us so much richer than they ever dreamed was possible.”**

To the memories of Rose Marie Coglianese Harrington (1913-1996) and William Joseph Harrington (1911-1999).

__________

*Bell, Daniel. 1979. The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism. London: Heinemann Educational Books. p. 273.

**Solow, Robert M. 1974. “The Economics of Resources or the Resources of Economics.” American Economic Review 64: 1-14.

Comments 4

Molly — February 3, 2010

Hi Brooke,

I am currently taking an Organization Theory management course at Bucknell University and I found this post very insightful as it relates to the material that we are studying. Family structures are organization in and of themselves and it is interesting to relate organizational concepts present in these structures to concepts present in corporate structures. For example, the idea of working under a "glass ceiling" in the corporate world is the feeling an employee gets when he or she is unable to move upward in their company. They are assigned specific duties within a position that they feel they are "stuck" with. People who are affected by a corporate glass ceiling begin to lose their motivation since they feel as if their talents and capabilities are not being utilized to the maximum potential. I feel like this idea can be related to the family structure from the post-Great Depression. Although these families were performing purposeful duties necessary for survival, they were constrained by a "glass-ceiling." They could not pursue their specialized interests because they did not have the means of doing so. They were forced to perform the same tasks everyday with no opportunity for "advancement." This situation can also lead to one feeling as if their talents and capabilities are not being utilized to the fullest potential.

Michael E. Marotta — February 22, 2010

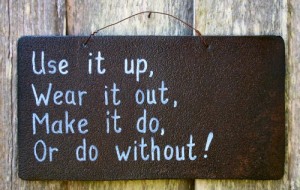

"Use it up. Wear it out. Make it do, or do without." was a slogan of WORLD WAR TWO, not The Great Depression. Much of that propaganda effort -- victory gardens; silver in the 5-cent coin to save nickel for armor plate -- were economically unnecessary but politically expedient. We here today do not understand that even Pearl Harbor was seen then differently, as most people had no idea for YEARS what the real damage had been. (Time magazine predicted that the US Navy would launch a counterstrike against the Japanese homeland from the Philippines. Little did they know...) The need for the propaganda was the uncertainty in Washington that the people would be in favor of war.

"Make it do or do without" was how people lived anyway -- despite a decade of the Roaring Twenties. Consider the lifestyle evidenced in Arthur Miller's "Death of a Salesman." And, at that point (December 1941), the Great Depression was still in full tilt. "War production" achieved no wealth creation because when a bomb explodes, all of the resources that went into making it are lost, as well as whatever it destroys. (If having money in your pocket makes you rich, why isn't Zimbabwe the new Switzerland?) So, people remained poor, which is how most people in most times actually live.

Improved living standards came as a result of capitalism. As the markets were regulated and controlled and manipulated by non-market forces, impoverishment was the inevitable consequence. Therefore, government slogans for frugality only made a virtue out of a necessity.

Alan Sloane — February 22, 2010

I thought this was a *lovely* piece of sociological writing, and epitomized what I enjoy about Sociology. It moves from (high) theory (Bell) to substantive (personal experience) and back to theory (Durkheim and Solow), but integrating the three sets of insights and coming up with something distinct.

I came back to store away a bookmark, so I could use it as an example in teaching, and was sorry not to be the first to comment.

Much appreciate the article!

Thrifty is Nifty - Simple Faithful Open — July 30, 2011

[...] More DIY inspiration: Reuse Tues from Itty Bitty Impact A Handwritten Letter is somehow more personal. Mini DIY Tech Solutions that I never think to use until I trip over the cord. Again. A Few More Thoughts… [...]