This time around, there was prescribed pain medication involved—hooray—but it was of a kind that could kill you if you took too much. So reading and understanding the package directions was actually important. Imagine my surprise to open that package in my hour of need and find that the insert contained pages of directions, but only in German. Not one word in any other language: as if it never occurred to the manufacturer that non-German-speakers might find themselves in Germany, sick and in need of this common pain medication. As if there were no such thing as a tourist, or an immigrant worker.

In case the reasons for my surprise aren’t clear, I should point out that Germany is a relatively small country (by American standards) surrounded by neighbors who speak other languages: French, Italian, Dutch, Danish, Polish, etcetera. Internally, Germany also has a large number of immigrant groups in its population, the largest of which is Turkish. But was there any Turkish, or French, or Italian to be found on that package insert? Nein!A thousand times nein! Because anyone lucky enough to get into Germany should have the courtesy and intelligence to read German, right? Especially medical German, of the kind printed on the package insert for this pain medication.

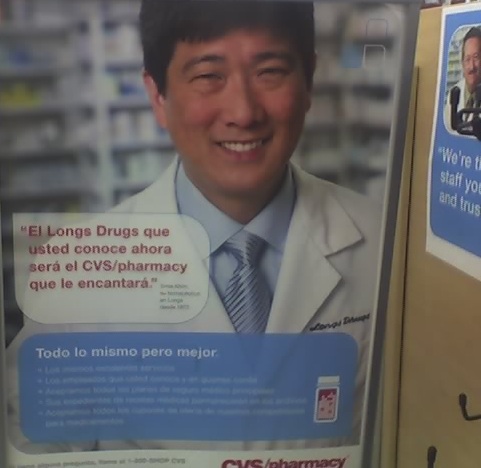

So I sat in the bathroom with a dictionary at 3am, barely able to focus my eyes from the pain, trying to figure how to avoid killing myself by accident with the pills that were supposed to bring relief. Obviously, all’s well that ends well: I am not blogging from beyond the grave. But it got me thinking wistfully about the ways in which American drug manufacturers and pharmacies go way out of their way to avoid this sort of situation happening in the US. When I was in California a few weeks after wrestling with the pain meds, I stopped by a CVS and had to smile at images like the one above, of the Asian pharmacist with the caption in Spanish, and this sign—displayed near the prescription drop-off window—explaining to customers how to get help in 21 different languages, including English, Laotian, Polish, Portugese and German! (Please forgive the poor quality of my camera phone shots.)

Now this kind of outreach to non-English-speaking populations obviously doesn’t occur just as a humanitarian gesture: it’s a business decision by firms that want to make money by reaching out to the widest possible customer base. This means eliminating obstacles to the use and purchase of medical products—like language barriers. Despite all the crummy pockets of English-only activism in the US, American firms still want to make money, and that keeps them printing signs and package directions in lots of non-English languages—because they recognize the reality that many people in the United States, whether tourists or immigrants, don’t speak English at all, or don’t speak it well enough to decipher things like dosage directions while in pain in the middle of the night.

The question is: why don’t German firms recognize that? Why don’t they recognize that non-German-speakers within Germany have money to spend, and try reaching out to them—for instance, by making package directions available in other languages? Leaving aside the safety issues—it says something about German culture and its stance on foreigners that potentially dangerous medications are not labeled in any language other than German, or even in pictograms, which are commonly used elsewhere in the world as a language barrier workaround—it seems that German firms are forgoing some profits by making their products hard to use by non-German-speakers.

At root, I believe, this is about culture. Shortly after my arrival in the country, many Germans told me to be prepared for the total absence of American-style service culture. But that was only part of the story: after three years in Germany, what I notice is not just the absence of something like service orientation, but the presence of a cultivated user-unfriendliness, in which making things difficult and exclusionary is very much an explicit goal rather than an unintended consequence.

This is one of the many instances where conventional economic wisdom—all businesses wants to maximize profits—breaks down, and economic sociology can be very helpful. Because it’s not that hard to find places where entities nominally called businesses seem hell-bent on making it difficult for people to buy and use goods and services. The whole culture of capitalism as Americans know it is not universal, even though many US political and economic leaders would have us believe that those norms and values are shared everywhere that business is transacted. If you’ve ever been to a socialist or communist country, you know this already; but it is perhaps more surprising that one finds such substantial deviations from American, customer-oriented norms in countries known as developed capitalist democracies.

Like Germany—where two of my German friends recently got “fired” from their long-time health club because they complained to the owner that her employees were 10-15 minutes late almost every morning at opening time, leaving a crowd of members waiting around for the front doors to open. So instead of apologizing or trying to remedy the situation, the club’s owner told my friends that they were banned from the club henceforth as complainers who “upset the staff” with their unreasonable demands for things like reliable opening hours. Now that’s customer service! (I did find a tiny speck of consolation in this story: I thought that kind of thing only happened to foreigners like me, whose accents and grammatical errors while speaking German gave us away as members of a lower caste.)

Economically, this is just insane: what kind of business owner fires her own customers when they complain about her business failing to live up to its commitments? Wouldn’t it seem easier just to make sure the doors of the club got opened on time, rather than losing the revenue stream from customers of years’ standing? I suppose an economist would say that the club owner was maximizing her utility—whatever that means in this case. The utility of being able to cut off her nose to spite her face? To “win” a power play, but lose money in the process? Certainly, many people are willing to pay dearly for the experience of power and dominance over others. But whenever this sort of thing gets explained in terms of economic theory, I find the term “utility” deeply unsatisfactory: like a giant black box in which economists throw everything that they don’t understand.

Sociology is sort of like dumpster-diving in that black box: that’s where all the interesting stuff can be found. Like the costly, irrational stuff people do in the name of culture and preferences. There are a number of different definitions of culture across the social sciences, but I see it as the broad set of social values, practices, norms, roles and expectations people have because of the setting in which they were raised, or in which they live. Nothing happens without culture, including capitalism. And this is a major insight of economic sociology: there is no one universal capitalism, but numerous local variations, dependent upon culture. (Paging Max Weber—again.) So I come from a world in which the business norm is “the customer is king”—whether or not an individual transaction actually lives up to that ideal, I can call upon it within the US and most people will a) know what I’m talking about, and b) acknowledge that it’s the ideal to which business should aspire.

Go to Germany, however, and both a) and b) would cease to apply: there is no shared cultural agreement that customers are the most important people in a business transaction. That changes everything about the lived experience of economic activity there: things that would be unthinkable in the US can happen in Germany, like the gym owner firing my friends for their service complaints.

This produces a special kind of culture shock, of the specifically economic variety. It’s not something I’ve ever seen described, either in the scholarly literature or the popular press. But I’d venture that it happens to most of us, even when we travel outside our home countries: every time you find yourself in a new country, wondering if you’re supposed to leave a tip, and if so, how much, you’re experiencing a minor form of economic culture shock. But the phenomenon manifests itself in a variety of other ways that are hard to fully appreciate until you move to that new country and start working there, buying groceries, and going to the doctor.

Having shared a few stories about the way that economic culture shock has affected me, I’d be interested to hear from you–what forms have you encountered, and what did you make of those experiences?

Comments 8

Benj — October 5, 2009

This describes well my experience in Cairo. Sitting with friends near the main market area, I was being constantly heckled and interrupted by street vendors (mostly offering a shoe shine -- despite my sneakers -- 11 shoe shine offers in 20 minutes). We decided to sit in a nearby cafe, thinking thus to avoid the vendors. They just followed us. We asked the waiters to run interference or keep the vendors out of our area, and they refused, even when we suggested that we might leave (we were perusing the menu at that point) or refuse to tip. To them, it simply didn't make sense that the customers' preferences should be paramount. (Besides, we'd be gone in a half hour or so, while the vendors are there all day, every day.)

Josh — October 13, 2009

Waiters in the US interrupt your meal to ask you how everything is going and if you need another drink = good thing.

Waiters in the everywhere else interrupt your meal to ask you how everything is going and if you need another drink = way to get a bad tip (if they even tip there ha!).

I much prefer the former.

Best Sentence I’ve Read Today « The Sociological Imagination — October 13, 2009

[...] Brooke Harrington trying to explain why German drug companies only have directions in German despite the large [...]

phil — October 20, 2009

Great stuff! German political culture isn't too different, either: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=laUJzGMUEI4&hl=de Why speak English when you could just assume to be speaking the most sensible, logical language in the world?

RabidAltruism — October 28, 2009

Your Germany anecdote resonates with my experiences studying abroad for a year in Tanzania; if you traveled to some of the few more expensive areas in the former capital, Dar es Salaam, there was always a curious juxtaposition between the modernity of the often South Africa-funded shops and the level of what might be called professionalism/a customer-service orientation on behalf of the staff.

Particularly intriguing was the behavior of waitstaff; I often had waiters/waitresses forget my order (sometimes repeatedly) or seemingly ignore my table (before or after having ordered) for upwards of 20 minutes (this in a very small restaurant, with myself being the only customer in some of these stories). My hesitating analysis is that the business/service culture in Tanzania, or at least in Dar, is simply much more relaxed than in the United States; instead of a sense of, "The customer must have what he/she wants a.s.a.p.," there was a sense of, "I'll get around to your food/drink/etc.; let's just relax a bit in the indefinite meantime."

intet — February 12, 2010

Hi! This is a very interesting post, but I think this post is pulling together quite different phenomena and that there is more to this than just "friendliness" or not.

I entirely agree that vital information, such as that regarding medicine, should be available in as many languages as possible, but I think this should be a matter of public service, not consumer service.

While I see how this "unfriendliness" you have encountered in Germany can be bothersome (the example with the gym is really bad), I think this "economic culture" where the consumer isn't king is ultimately a sign of a more equal, less capitalistic society.

For example, travelling as a Western tourist in tourist locations around the world (from Southern Greece to Thailand), you would often find people working in restaurants, hotels and shops that cater to tourists to be very service-minded. Large cities like Cairo are exceptions, since they are less dependent upon tourist money: they don't need you(r money) as much.

Or, another example: when the economic recession hit Sweden recently (a country that an American would probably find as un-service-minded as Germany), articles started appearing on how young people's attitudes were changing towards becoming more "service-minded" (which was applauded by right-wing commentators) -- since the rising unemployment meant people became more dependent on keeping the job they had, they had to be more subservient and put up with more. So while Germany and Sweden may have less "friendly" service, there is less of a class divide, more of a social security net, stronger unions guaranteeing worker's rights and so on. Being rich in the US might be better than being rich in Germany, but being poor in the US is far worse than in Germany -- and this ties into service "friendliness" towards consumers.

So, essentially, being service-minded is a sign of subservience, of the lower classes bowing to the upper classes. In the US, you have a greater class divide and a more deeply capitalistic, consumerist culture than in many European countries. A society where the "consumer is king" necessarily means that "cash is king", since the worth of a consumer is tied to his spending power. If you're rich in a capitalist society, and if peoples' jobs and livelihoods depend upon your spending habits, of course you're going to encounter "friendlier" service personnel. But they aren't friendly for the sake of being friendly or helpful (as between equals), they're friendly because they have to in order to encourage you to consume, so that they can keep their jobs. They're friendly towards you because of your (percieved) worth in economic and class-related terms.

intet — February 12, 2010

Sorry for double-posting, but it just occured to me that you could put this in terms of gender, as well, as an analogy and example: in Western patriarchal society, men often expect women to "smile" and be friendly towards them. If women aren't excessively friendly towards men, they're seen as very unfriendly. This is of course a way of upholding patriarchal hierarchies based on gender: to be "friendly" is, as said, to be subservient (in a hierarchical context!).

Charles H. Green — August 30, 2010

Interesting example. It's very easy for an American to slide into seeing this as a value judgment (I know that's my first instinct). But, as several of the above commentators above have noted, it's best seen as a case of "it is what it is," with its own attendant set of cultural assumptions.