Did you notice that international stock markets had a little party this week, despite worsening economic news? The latest US unemployment report is shockingly bad, most of the nation’s retailers are reporting double-digit declines in sales (bad news in a country where consumer spending represents two-thirds of GDP), and American stock markets remain in the tank, with the DJIA 40% lower than this time last year. And things don’t look much better in Europe and Asia, where signs of recession are multiplying despite frantic efforts to shore up their economies with stimulus packages and interest rate cuts.

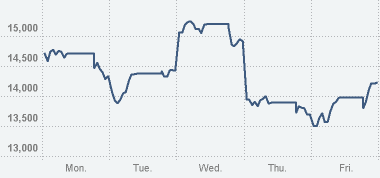

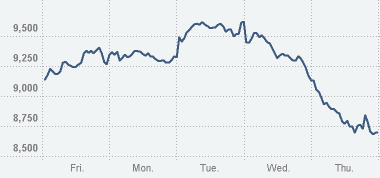

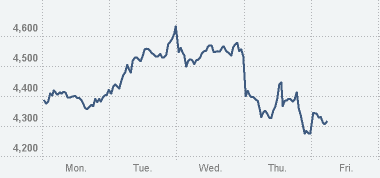

So what should we make of the chart on the right?

It shows Japan’s Nikkei Index, which–despite all the bad news, and with no end in sight–experienced a significant surge on Wednesday.

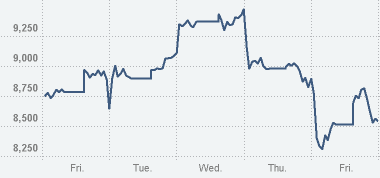

In fact, markets around the world did a little happy dance following the US Presidential election.

Did someone declare a global holiday from doom-and-gloom?

Whatever it was, the words “President-elect Obama” seemed to make financial markets temporarily giddy and blissed-out, much like spectators in Grant Park on Tuesday night.

Here in Germany, people are celebrating and offering congratulations to any American they meet. They were practically singing “forget your troubles, c’mon get happy”–an unexpected burst of optimism in the nation that coined the term schadenfreude .

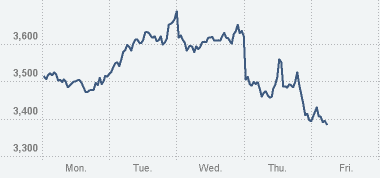

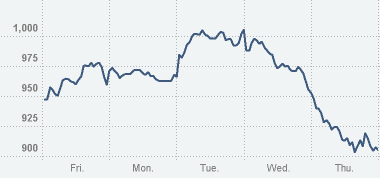

But it looks like Wall Street didn’t get an invitation to the party.

While the Dow was up on election day itself, once the results were in, it went right back down.

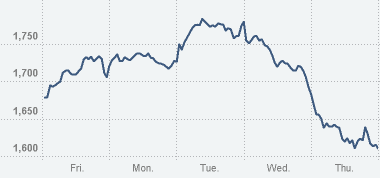

As did the S&P 500…

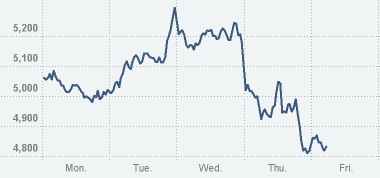

..and the NASDAQ.

Maybe the US markets are more in touch with the grim reality of the world economic crisis. Or maybe US markets are just more sanguine than others. That interpretation might seem risible given the extreme ups and downs we’ve seen in the past month, but it’s supported by the historical evidence. Over the past 50 years, momentous events in politics have rarely made much of an impact on US stock prices. Indeed, Cutler, Poterba and Summers showed in their 1989 Journal of Portfolio Management article that even events of world-historical significance, like the JFK assassination or the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, have barely registered on the US markets.

Which makes it all the more fascinating to see the financial exuberance (which may or may not be irrational) that greeted the news of Obama’s election overseas. Let’s see if there’s another surge on Inauguration Day. And here’s hoping that next time, the party will last a little longer and include the US markets.